Unit 3 — Part B. Harvey County: Home of Trails

Over many generations, Harvey County has been heavily traveled since the area is a major crossroads of trails. These trails were created and/or used by wild animals, Native Americans, Spanish explorers, military units, gold prospectors, cowboys, pioneers, immigrants, travelers and local residents.

The stories of the trails illustrate “No man is an island entire of itself.” No one is truly self-sufficient. No one functions in isolation. People rely on and/or are impacted by others. Their actions produce threads connecting them to others. The threads can be very obvious or barely discernible. The challenge is to identify the threads, determine who was impacted, name what elements came into play and then recognize the short-term and long-term ripple effects.

The truth in “No one functions in isolation” is quite evident in the cattle trade business of the last half of the 1800s. That being the case, Part B of Unit 3 focuses on how and why various cattle trails were created; and, specifically, the role of those which traversed Harvey County. Part B of Unit 3 looks at the interplay between trails and communities. It also examines myth vs. reality.

Click the first illustration to start the pictorial narrative of cattle trails within Harvey County.

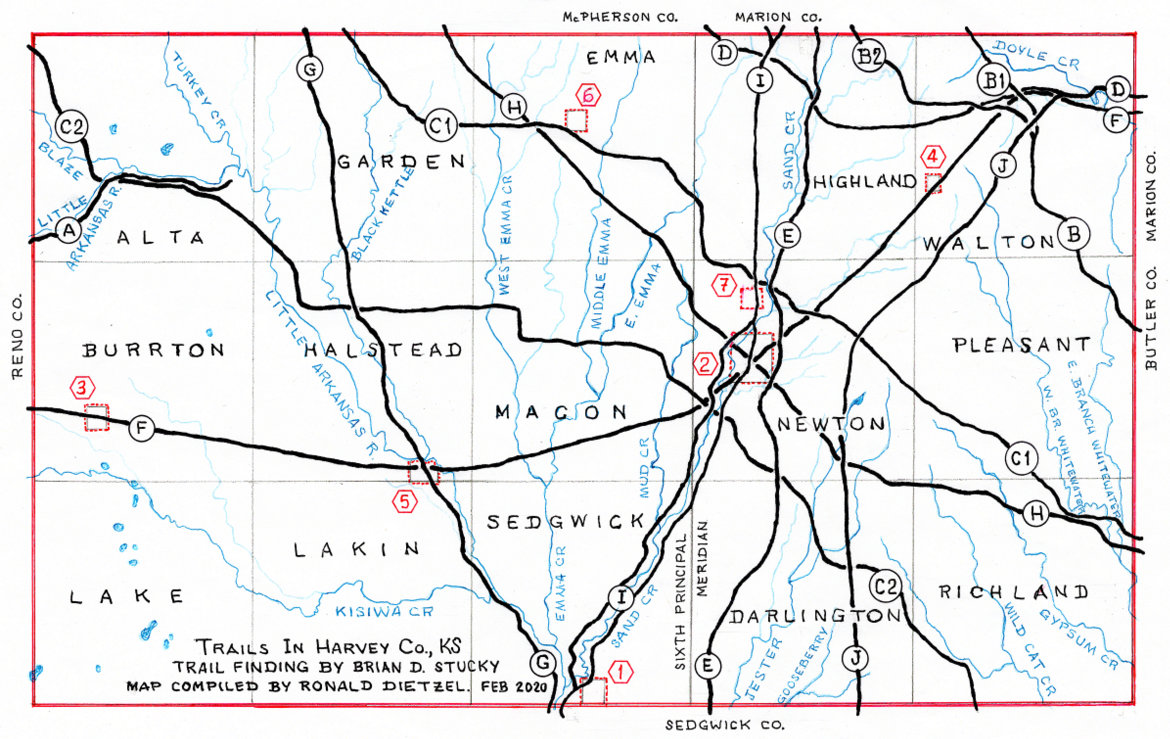

- Of the twenty-one trails within Harvey County, Unit 3 provides narratives for a dozen of the more noteworthy ones. Unit 3-“Home of Trails” is divided into two sections. Part A contains descriptions of trails used by explorers, gold rush participants, military units, travelers, immigrants and homesteader groups (marked as A thru H). Part B describes cattle trails which traversed the area that would become Harvey County (marked as I and J).

- Part B of Unit 3 contains narratives for the cattle trails (marked as I and J on the map). Within the variety of twenty-one trails that ran through Harvey County, the map shows a dozen of the most significant trails. As an 1870 representation of the area, the hand-drawn map depicts the area prior to the existence of Harvey County or its cities or the railroads. In order to give points of reference, the map shows the future boundaries and names of the townships as well as the future sites of the county’s cities.

- Cattle – An Economic Force That Repurposed Trails and Generated Laws. The Spanish land grant system encouraged cattle ranching. As a result, Texas cattlemen searched for an outlet to sell their cattle. 1820s Anglos in Texas moved herds to New Orleans. Cattle were trailed to the 1848 California gold fields and the 1858 Colorado gold fields. For various reasons, herd sizes to these markets had a limit of about 250 head. In time, Texas ranchers realized the eastern markets were more profitable since northbound herds could have 2,000 or more head. Knowing this, 1840s drives began on the Shawnee Trail (Eastern) System (1846 – 1875). Cattle were taken north across Indian Territory (I.T.) and through the eastern Kansas Territory so as to reach buyers in Missouri, Illinois, and other Midwest states. However, obstacles developed in the 1860s. The Civil War blocked much of the shipping; and then ever increasing numbers of Plains Indians and Euro-American settlers occupied the land. Since the longhorn cattle often carried a disease which was deadly to local domestic cattle, the movement of Texas cattle was restricted. Through quarantine line laws, Texas cattle were banned from entering specific regions. Trail drivers had to endure the ire of local farmers and ranchers in Indian Territory, Kansas and Missouri. Drovers faced encounters from ruffians (Kansas Jayhawkers and Missouri Bushwackers) who were still active after the guerrilla warfare of the past decade. As a result, drovers were looking for “a good, safe place to drive to, where he could sell or ship his cattle unmolested….” Note: In the mid-1890s, it was finally determined the Texas Fever (aka as Spanish Fever) was caused in domestic cattle by longhorn cattle which carried south Texas coastal ticks. Hwy K-15 marker in Harvey County. Photo credit: Ronald Dietzel. October 2018.

- Trails and Expansion of Rails Linked Supply and Demand. When the Civil War drew to a close in 1865, the plains of Texas had huge numbers of cattle for which there was no ready market. Cattle on the Texas range were offered for sale at one to two dollars per head. In the eastern U.S., there was a high demand for meat with a good animal selling for as much as $40 per head in Chicago. To join the supply with the demand, a large scale supply chain was needed. The challenge was to establish key links; and to get the links in place in a simultaneous manner. First, railroads needed to extend westward so cattle could be shipped from the Great Plains to the eastern markets. By 1866, thousands of Texas cattle were unsold since drovers could not get their herds to existing rail lines. Due to Texas Fever, they were blocked by Missouri and eastern Kansas quarantine lines as well as violent retaliation against the cowboys and their herds. Link #1 went into place when the Union Pacific, Eastern Division (which became the Kansas Pacific Railway [K.P.R.] in 1869) extended its line in 1867 to the village of Abilene, Kansas. Second, a cattle terminal needed to be established – one which would be convenient, safe, dependable and offered proper shipping facilities. Link #2 fell into place through the efforts of Joseph G. McCoy, an Illinois cattle buyer. He arrived in Kansas in 1867. After being rebuffed by more than one town due to a fear of the Texas Fever, McCoy was able to construct stock yards, a hotel, offices and support facilities at the tiny village of Abilene, KS. Since the quarantine boundary was about sixty miles west (i.e. about at Ellsworth), it was illegal to trail Texas cattle to Abilene in 1867. Longhorns went to Abilene anyway. Third, drovers needed a route to trail their herds from Texas to railheads and livestock markets in Kansas, Nebraska and Colorado during the mid to late 1860s; and then later to Wyoming, Montana and the Dakotas. Depending on their starting point, they’d cover as much as 700-800 miles and would be on the trail for up to two months. Link #3 involved Texas cattlemen often using the trails originated at an early date by Native Americans. Being familiar with the natural topography, various tribes had created routes that used the easiest way through hilly terrain and took advantage of the best fords for river and stream crossings. Trails did not go in a straight line since they took the path of least resistance which led to dependable water sources and abundant grass for livestock. Photo credit: https://www.kshs.org/kansapedia/railroads-in-kansas/15120 03/04/2019.

- Trails and Expansion of Rails Linked Supply and Demand – continued. As the trail drovers and the railroads kept pace with changing circumstances, four cattle trailing systems developed – the Shawnee Trail System of 1846-1875; the Goodnight Trail System of 1866-1885; the Eastern, Abilene and Chisholm Trail System of 1867-1889; and the Western Trail System of 1874-1897. Each trail system resembled a tree rather than a straight-line single path. Having a large root system spread out over Texas, a trail system came together into a main trunk which worked its way through Indian Territory. In the north, it branched out to the various delivery locations. The trail systems were not separate entities of their own. The systems overlapped. Each trunk line had feeder and splinter routes. The first cattle drovers did not “blaze a new trail.” Quite often, cattle trails were a repurposed existing track – an old military road, an overland freight route, or an emigrant road. In turn, those earlier paths had often followed Native American or wild game trails. Note: Most of the ruts and swales of the cattle trail in Harvey County have been erased by farming, stream management and construction. The photo above shows one of the few remnants of the Abilene/Chisholm Trail (its formal name within Harvey County). Ruts are grooves in the ground, often made by vehicle wheels and/or the hooves of livestock which have cut through the prairie sod. A swale comes from ruts that have been deepened by weather and erosion. These features are physical evidence of the passage of large numbers of cattle and the weight of wagons loaded with provisions. Remnant of Abilene/Chisholm Trail, north of Kauffman Museum in Chisholm Trail Park, North Newton, KS. Photo credit: Ronald Dietzel. April 2019.

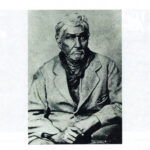

- (I) Eastern, Abilene and Chisholm Trail System of 1867-1889 – A Cattle Trail. Within today’s Harvey County, a prominent cattle trail came from the south. It skirted the west edge of today’s city of Sedgwick. The trail paralleled both sides of Sand Creek and went through today’s Newton. Going north from there, the route was in close proximity to today’s Hwy K-15 as it continued to Abilene, KS. In the 1860s and 1870s, the drovers and others involved in the cattle business referred to this route as “The Trail,” the “Abilene Trail,” the “Kansas Trail,” the “Northern Trail” or the “Texas Trail” when they spoke about trailing cattle through central Kansas. Formally mapped as the Eastern Trail, Abilene Trail and Chisholm’s Trail, this trail system was a linking of several existing trails. Using the old Shawnee Trail (Eastern in Texas) from south Texas to Waco, it went up the western fork, the Shawnee – Arbuckle Trail, to go through Ft. Worth and across the Red River to the (south) Canadian River in Indian Territory. It utilized an old freight route, Chisholm’s Wagon Road, between Fort Arbuckle, the N. Canadian River and the Cimarron River. The Black Beaver/Col. Emory Trail was used from there to Wichita. The Wichita to Abilene leg paralleled much of the six year old Black Beaver/Emory Trail. Joseph McCoy directed Timothy Hersey and a crew to construct mounds of dirt to guide drovers from Wichita to Abilene. By following the common path used by the expeditions of Cpt. Marcy/Black Beaver in 1849, Maj. Hamilton W. Merrill in 1855 (Fort Belknap, Texas to the mouth of the Little Arkansas River), Col. Emory in 1861 and Jesse Chisholm’s wagon route, the first herd to Abilene plus all the subsequent herds followed an existing trail to get to Hersey’s 1867 route. Jesse Chisholm (1805 or 1806—1868). Photo credit: https://www.kansasmemory.org/item/25070. 22 Mar 2020.

- (I) Eastern, Abilene and Chisholm Trail System – Nicknamed the “Chisholm Trail.” Less than half of the volume of cattle driven from Texas traveled this trail; one which was shorter in length than later trails that led to Nebraska, Colorado, Wyoming, Montana and the Dakotas. The Eastern, Abilene and Chisholm Trail was not the first cattle trail from Texas nor was it the last. It was one of several routes used by Texas drovers to move their herds to the railheads and livestock markets. Compared to today’s practice of naming everything, cattle trails during their time of existence were often not known by any name. If the drovers did name them, it was usually for the destination or a landmark along the route. For the specific cattle trail which went through Harvey County, the various drovers’ names from the early days were listed on the previous page. The most used were the Abilene Trail and the Texas Trail. Eventually, the trail was called by a nickname, the “Chisholm Trail,” a misnomer which suppressed the other names. Since the early 1900s, the “Chisholm Trail” received more publicity than all of the other trail systems combined. While it was certainly important and had its place in history, the propaganda and promotion of the nickname was such that, in the 1910s and 1920s, the trail moved into the realm of folklore. Developing into a body of popular myth and unsupported beliefs, the nickname and major misperceptions of the trail’s location and length cemented themselves into the public’s mind. As a result, facts have been obscured and overshadowed by legend. Having started as a trade route and simple cow path during the cattle trailing era, the “Chisholm Trail” has become the focus of folklore and tourist attractions, museums, shopping centers, schools, restaurants, casinos, hotels, etc. In turn, there’s been a 100 year old controversy and debate over the folklore vs. the reality of the Eastern, Abilene and Chisholm Trail System (and, in turn, the Abilene/Chisholm Trail portion). Abilene/Chisholm Trail marker on Bethel College campus, North Newton. Photo credit: Ronald Dietzel. October 2018.

- (I) Eastern, Abilene and Chisholm Trail System – Reality and Evidence vs. Folklore. The debate is multi-faceted. One element involves the namesake of the “Chisholm Trail” since credit has gone to Thornton Chisholm, John S. Chisum and Jesse Chisholm. Folklore claims additional men should be credited because their name was Chisholm, Chisum, Chism, Chissum, Chisolm or Chissm. Evidence shows Thornton Chisholm left DeWitt County, Texas (east of San Antonio) in April 1866 with a herd of 1,800 cattle. Thornton’s route went about 100 miles west of the 1867 trail which developed into the “Chisholm Trail,” angled through Indian Territory without using the Chisholm Wagon Trail and ended in St. Joseph, Missouri. In 1868, Thornton died in a freight hauling accident. With these facts, Thornton can be ruled out as the namesake as can John S. Chisum who ranched in Denton County, TX (north of Ft. Worth) until 1863 when he moved his operations to Coleman County (east of San Angelo). 1867 brought another major change for John Chisum when he established his ranch in New Mexico Territory. There is no evidence showing any of Chisum’s cattle were driven to Abilene, Kansas in 1867. Jesse Chisholm, a trader and translator, operated several trading posts in Indian Territory and southern Kansas. He opened his first trading post in 1847, added more in the late 1850s and then again in 1864. In moving supplies back and forth, Jesse’s heavy wagons turned an existing Indian/military trail in the central part of Indian Territory into a very discernible path. Some knew this as Chisholm’s Trail and others knew it as the Chisholm Wagon Road. The “Chisholm Trail” nickname was derived from Chisholm’s Trail/Chisholm Wagon Road in spite of Jesse’s supply route comprising only a small fraction of the total miles of the cattle trail system which emerged in 1867 as a means of getting Texas herds to Abilene, Kansas. Evidence shows Jesse Chisholm was not a cattle drover, did not establish a trail into Texas and did not extend his trade route north of today’s Wichita. Due to his death in 1868, Jesse never knew anything about a “Chisholm Trail” which was used to trail Texas cattle. The “Chisholm Trail” name first appeared in newspapers in 1869 and then became a bit more common in 1872 after Abilene left the market. Men loading Texas cattle on a Kansas Pacific Railway stock car at Abilene, Kansas. Leslie’s, August 19, 1871, page 385. Photo credit: https://www.kansasmemory.org/item/208507. 4/8/2019.

- (I) Eastern, Abilene and Chisholm Trail System – Non-trail Entities Wrongly Defined It. After Abilene’s 1871 cessation as a cattle town, cartographers continued to base their maps on military surveys and used the “Abilene Trail” label. However, many others embraced the “Chisholm Trail” term so there were different versions regarding the trail’s name and location. James R. Mead (a friend of Jesse Chisholm) exploited the name to grow his interests in the new village of Wichita (incorporated in 1868). The nation’s eastern population developed an interest in “The West,” cowboys and outlaws. The nickname became a convenient catchphrase for a ready market in “frontier” stories for newspapers, books, dime novels, songs and silent films. Since the public expected entertainment that was full of thrills and chills, writers focused on sensationalism and embellishment rather than reality and fact. This fed the public’s misperception of the “Chisholm Trail.” The name was haphazardly applied to include any post-Civil War cattle trails leading from Texas; as well as to the Texas portion of various trails. In the 1910s and 1920s, the name was heavily promoted for the “Good Roads Association” highway projects in Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas which became the Meridian Highway (today’s Hwy US-81). The “Chisholm Trail” nickname served as a tag line for the cities and counties that stood to benefit from a highway which would bring tourism and commercial advantages. It cemented the misperception that the “Chisholm Trail” started in south Texas and took a straight line all the way to Abilene, Kansas. Since many traces of the old Texas cattle trails had disappeared by the 1930s, folklore said the trail had taken the route of the Meridian Highway, even though the two were miles apart at many points. The scope of the folklore expanded when P.P. Ackley, a former drover, funded a 1930s project to “mark the Chisholm Trail” and, without having supporting documentation, placed signs from Brownsville, Texas to Canada. Texas rancher and historian Tom B. Saunders IV said, “What is more important than the trail name are the people who actually did all the work.” Researcher Wayne Ludwig then said, “The drovers…who got the job done…deserve to have their history recorded as faithfully as possible.” https://slideplayer.com/slide/14521208/90/images/27/DIME+NOVELS+Dime+Novels.jpg March 2020.

- (J) Four Horsemen of Wichita, 1871 (Clearwater-Wichita-Florence) – A Cattle Trail. Having been a bison migration path, a well traveled Native American route, an 1861 Yankee “escape” trail in the Civil War and then a corridor for shipping and delivering goods and supplies to trading posts, the Abilene/Chisholm Trail was well established as drovers moved cattle from Texas to Abilene, KS. In spite of this, a period of brief but fierce competition resulted in the forming of the Four Horsemen of Wichita Trail of 1871. This short-lived and little known route went from Clearwater to Wichita to Florence. It’s role in shaping south-central Kansas could be considered just as instrumental as that of the famous Abilene/Chisholm Trail. The Four Horsemen Trail’s story also illustrates the thin thread that can exist in determining the lives and futures of people and communities. Even though Wichita, Park City, the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway (AT&SF) and the Kansas Pacific Railway (K.P.R.) were the key players in the Four Horsemen story, the tale is worth telling due to the long term implications for the futures of Newton and Harvey County. In a nut shell, the creation and survival of Newton was due partially to the ascendancy of Wichita and the demise of Park City as well as the AT&SF’s success in reaching Newton’s planned townsite in July, 1871 where its trains intercepted the cattle herds. The back story of the Four Horsemen Trail follows. Note: Not to be confused with 20th century Park City which is located on the north edge of Wichita, the 19th century Park City was fourteen miles northwest of Wichita (more or less west of today’s Valley Center) at a site on the Arkansas River. Northwest side of Newton at N. Anderson Ave and Northridge Rd. Photo credit: Ronald Dietzel. October 2018.

- (J) Four Horsemen of Wichita – Survival Meant Fierce And Cut Throat Competition. The last half of the 1800s was a time of fierce competition between railway companies as they fought for long-term survival. It was the same story with the towns. Looking at the monies generated by the cattle shipping business and its impact on the village of Abilene and the K.P.R., other towns as well as the AT&SF looked toward the cattle business to ensure their own futures. In 1863, the K.P.R. began constructing its main line westward from Kansas City. By 1866, the line reached Junction City and in 1867 it got to Salina. Because the AT&SF got a late start in 1868, an intense rivalry developed as the AT&SF played catch up with the K.P.R. Beginning in eastern Kansas and pushing west, the AT&SF line reached Emporia in July 1870 and the infant town of Florence in May of 1871. Paralleling the railroad strife was a fight for survival between the infant settlements of Wichita and Park City. It started with a major clash over both wanting to be county seat when Sedgwick County was organized in 1870. Believing its location made it the prime candidate for county seat, Park City suffered a severe blow when Wichita got the designation. Having lost out, Park City pinned its hopes on getting railroads and the Texas cattle trade. With multiple trading posts located in Wichita as well as a location on the generations-old natural trail which had been repurposed as a cattle trail, Wichita had a distinct advantage over Park City. Wichita’s merchants benefited by being able to sell supplies to the drovers and cowboys as they went through on their way north to Abilene. As a result, Wichita traders realized a bonanza in 1869 and 1870. North Newton at Chisholm Trail Park, north of Kauffman Museum. Photo credit: Ronald Dietzel. April 2019.

- (J) Four Horsemen of Wichita, 1871 (Clearwater-Wichita-Florence Trail) – continued. Since Park City lost the battle for county seat, it put all of its eggs in one basket by trying to capture the Texas cattle business even though Park City did not have any natural trails around its site. In about July of 1870, a campaign was begun to promote Park City as the frontier’s supply headquarters. In trying to draw herds its way, Park City publicized its route to Abilene as 20 miles shorter than through Wichita; that cattle were stopped and drovers persecuted in Wichita; that the trail had been changed to Park City; and then mentioned (without listing) new drovers’ supply businesses. Promoted heavily was Park City’s location on the west side of the 6th Principal Meridian in contrast to Wichita’s position on the east side – and that the Kansas laws made it illegal for Texas cattle to be east of the 6th Principal Meridian. Wichita took notice of Park City’s campaign and circulated its own set of “facts” by claiming to be 35 miles closer than Park City; claiming their supply prices were lower; and, that their suppliers were “gentlemen in every respect.” Full protection was promised from the Cowskin Creek crossing south of Wichita to 15 miles northeast of town. It was pointed out that Park City had no natural ford and the crossing would be more difficult because of bluffs. Also, a Park City route would require the cattle to cross both the Arkansas and the Little Arkansas rivers. Not being highly confident in its publicity campaign, Park City increased the stakes through an alliance with the K.P.R. If the alliance was successful, it would mean a new cattle trail going through Park City and on northwest to Ellsworth, the site which was to replace Abilene as the principal K.P.R. terminus. Abilene/Chisholm Trail marker in Newton at West 4th St and North Plum St. Photo credit: Ronald Dietzel. April 2019.

- (J) Four Horsemen of Wichita, 1871 (Clearwater-Wichita-Florence Trail) – concluded. For the Park City to Ellsworth scheme to work, a new trail, a new town and new cattle loading facilities would need to be in place at the Park City site for the 1871 cattle season. Any setbacks would open the door to the AT&SF and Wichita. For its part, the AT&SF was not sitting idle. It rapidly pushed west with the goal of completing its rail line to a site on the cattle trail which was 25 miles north of Wichita. After that, the railroad planned to go straight west which meant the AT&SF would not dip southwest to Park City. Thus, the K.P.R. – Park City alliance could be a turning point. If it failed and cattle herds continued through Wichita, Park City would have neither a railroad nor the Texas cattle trade. Trying to tip the scales toward the K.P.R.–Park City alliance, Maj. Shanklin (K.P.R. agent from Ellsworth) met the first herds of the 1871 season at the Red River and guided them north. As the herds reached today’s Clearwater (KS), a farm dweller learned of Shanklin’s plan to divert herds to the new Park City –to–Ellsworth trail and rode into Wichita with the news. It was quickly decided to have N.A. English, Mike Meagher, J.M. Steele and James R. Meade approach and redirect the drovers through Wichita. Park City’s death knell began to toll when the “Four Horsemen” intercepted the herd west of Wichita and convinced the trail boss to use the trail going through Wichita. Also, the Four Horsemen had drovers sign a statement saying Wichita was the shortest and best route – and then distributed circulars all the way to the Red River. The result was the creation of the Four Horsemen Trail as cattle herds made their way north from Wichita. Leaving the Abilene/Chisholm Trail and going through today’s Harvey County, the herds were driven northeast to Florence – then the AT&SF shipping terminal – since the Newton railhead was not established until July of 1871. 1964 photo. West edge of Park City townsite looking toward Vincent J. Keeler residence. The depression was once a dugout.

- Demise vs. Survival: Components of Constant Change. Having lost the county seat battle and the Texas cattle trade as well as not being a site on either the AT&SF or the K.P.R. rail line, the fate of Park City was sealed. By December 1871, the Park City Town Company owners were settling the final debts which were incurred in the town’s promotion. Since the town was never incorporated, there was no need to give any legal notice about it’s dissolution. The townsite “owners” departed the area and Park City began to disintegrate physically. With no property deeds, many of the citizens went elsewhere since they had no legal rights. Of the few buildings and homes which existed, many were dismantled and moved to other area towns. By 1873, most of the evidence of the town had vanished. The few remaining vacant buildings were “blown away.” Dugout homes became depressions in the earth. The townsite was sold in 1877 for $13.02 due to unpaid taxes ($319.88 in 2020 dollars). Today, Wichita is a city of 400,000 and “Old” Park City is farm ground. The dashed dreams of Park City’s organizers allowed for the creation of Newton. The Four Horsemen Trail continued to bring cattle herds through today’s Harvey County so the AT&SF had incentive to get its rail line to the Newton site during the summer of 1871. Since the Park City to Ellsworth trail did not materialize, Newton was the closest railhead for the drovers. Its status in 1871 as the primary shipping terminal was further facilitated by an end in 1871 to Abilene’s heavy involvement with cattle shipping. West 2nd and Main streets in Newton. Signage for the “Newton Massacre” area. Photo credit: Ronald Dietzel. April, 2018.

- Newton’s Cowboy Era Was Short-lived Due To Constant Change. The interplay between Wichita, Park City and Newton plus the competition between the AT&SF and the K.P.R. were not the only components of change. 1871 was perhaps the most chaotic year for the cattle shipping business in Kansas. It was the last year for Abilene as a major player. Newton was born as a town and as a cattle shipping site when the AT&SF reached there in July of 1871. Ellsworth prepared for a plunge into the cattle shipping business. Junction City on the West Shawnee Trail was a viable player until early 1871 when the AT&SF reached Cottonwood Falls, shortening the route and cutting out Junction City. Schuyler in Nebraska became a cattle terminal on the Blue Valley Trail. Kansas was overpowered with 600,000 head of Texas cattle. To top it off, the following winter was diastrously cold. The cattle shipping hubs changed quickly and constantly due to, one, railroads proliferating as they extended their lines ever westward; two, because drovers sought to shorten the time of their cattle drives; and three, because of the massive influx of homesteaders and town dwellers who wanted more “civilized” surroundings. Newton’s role as a cattle shipping site was short lived because rail expansion continued at a fast pace. The primary shipping terminals moved to Wichita and Ellsworth in 1872. Next, shipping had to be moved to Dodge City on the Western Trail due to the 1875 cattle quarantine. Dodge City got loading facilities in 1875-1876 and shipped until 1884. In 1885, the Kansas Legislature enacted another quarantine line against Texas cattle. Since the herds were pushed ever westward, legislation in 1887 was proposed for a National Trail but no action was taken. The Texas-Montana Feeder Route (1884-1897) was developed which went into Colorado, Nebraska and the northern plains. Rural Harvey County. Photo credit: Ronald Dietzel. May, 2017.

- A Transformation of the Social Fabric. While some were lured by the “riches” of the cattle business, an increasing amount of people began realizing “you’ve got to be careful what you wish for.” The cattle business had negative aspects – the Texas Fever (Spanish Fever); and the “hell raising cowboys” with the fringe element of society which they attracted. Consequently, the get-rich-quick partnership of railroads and cattle was swapped for the long term viability of railroads and agriculture. With an explosion of activity in the later half of the 1800s, the region went through a relatively quick transformation. The landscape with its dirt trails transitioned to steel rails as railroads became common place. In turn, there was an enormous influx of Euro-Americans which brought about a transition and conversion of the social fabric in Harvey County as well as the surrounding counties. Cultures were impacted. The composition of the population was reshaped. Ways of life were altered. Occupations shifted. Multiple settlements and boom towns were created. A few survived while many vanished. One major transition with far reaching impacts was the shift from livestock to a focus on agriculture. An immense amount of people, supplies, equipment and goods needed to be brought into Harvey County. On the flip side, appreciable quantities of products and goods needed to be shipped out.

- Learn about transformations and transitions by going to Unit #4 Rails & Trains in Harvey County in the pictorial history series of “Short Stories of Harvey County, Kansas.”