Unit 3 – Part A. Harvey County: Home of Trails

Over many generations, Harvey County has been heavily traveled since the area is a major crossroads of trails. These trails were created and/or used by wild animals, Native Americans, Spanish explorers, military units, gold prospectors, cowboys, pioneers, immigrants, travelers and local residents.

Within Harvey, Marion, and McPherson counties, the sheer number of Native American and pioneer trails is staggering. Brian Stucky, an area historian and researcher, has suggested the region has a higher quantity of trails and more different kinds of trails than anywhere else in the Plains and Midwest states with the possible exception of Independence (MO), Fort Bridger (WY) and St. Louis (MO).

Because of the astonishing quantity of trails in the region, this presentation is restricted to those trail stories which pertain to Harvey County; and how they were purposed. As a further limitation of the subject matter, the focus is on the major trails which traversed Harvey County. Since the stories of the various trails have been summarized, researchers are welcome to use HCHM’s resources in order to obtain further details.

The stories of the trails illustrate “No man is an island entire of itself.” No one is truly self-sufficient. No one functions in isolation. People rely on and/or are impacted by others. Their actions produce threads connecting them to others. The threads can be very obvious or barely discernible. The challenge is to identify the threads, determine who was impacted, name what elements came into play and then recognize the short-term and long-term ripple effects.

Click the first illustration to start the pictorial narrative of the many trails within Harvey County.

- Of the twenty-one trails within Harvey County, Unit 3 provides narratives for a dozen of the more noteworthy ones. Unit 3-“Home of Trails” is divided into two sections. Part A contains descriptions of trails used by explorers, gold rush participants, military units, travelers, immigrants and homesteader groups (marked as A thru H). Part B describes cattle trails which traversed the area that would become Harvey County (marked as I and J).

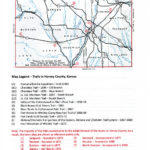

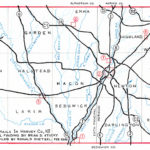

- Harvey County – Crossroads of Significant Regional Trails. Prior to Euro-American settlement of the area, an abundance of wildlife created a multitude of trails as the animals sought water crossings, protection, food sources and ways around obstacles. Many of these trails became the predecessors of the trails utilized by Native Americans over many generations. Repurposing continued as Euro-Americans appropriated the trails for their own transportation and traveling needs. A 1593 exploration trail is attributed to the Spanish Humana/Bonilla Expedition. Gold Rush trails consisted of the Cherokee Trail of 1849 and the Valley of the Cottonwood to Pike’s Peak Trail of 1858. Military trails included the Lt. Col. Morrison Trail of 1857; the Black Beaver/Col. Emory Trail of 1861; and, the Ft. Harker to Wichita Trail of 1868-69. Travelers used the Ft. Zarah to El Dorado Trail of 1871-72 as a shortcut off the Santa Fe Trail. Cattle related trails included the Abilene/Chisholm Trail of 1867-1871; the Stagecoach Return (Abilene, KS to Texas); and, the 1871 trail of the Four Horsemen of Wichita. Note: Within the general vicinity of many of these trails is the historical marker shown in the photo. The signage is located north of Newton in a small roadside park on Highway K-15 at the Harvey/Marion county line. Photo credit: Ronald Dietzel. October 2018.

- Harvey County – Crossroads of Local and Immigrant Trails. There were numerous local and immigrant trails. A few appear to have been connections between homesteads. An undated trail was the split from the Cherokee Trail which went to the Zimmerdale area (located between the present-day cities of Newton and Hesston). “Geary’s Ranch,” located near today’s Moundridge (in McPherson County), was on an 1868-1871 “trail used by travelers between Abilene…and Indian territory.” Roughly, the trail came from the south to Newton-Hesston-Moundridge and then north. The Cottonwood City to Perry Ranch Trail of 1869 may have been one of the first paths out of the Cottonwood/Doyle Valley which went to Sand Creek. In 1869, George F. Perry established a cattle ranch at the joining of the Emma Creek and the Little Arkansas River. This was one of the earliest settlements in the area. Note: Located near today’s Cedar Point (in Chase County), Cottonwood City vanished long ago. The 1870 Irish Trail to Garden Twp (in Harvey County) was used by the F.P. and A.E. Munch families. Also, in 1870, was a trail used by a French group to settle in Alta Twp (in Harvey County). Via an 1873 split from the Cherokee Trail, French Canadian immigrants used the Elivon Trail to populate their settlement called Elivon. Located just inside McPherson County and north of today’s Hesston, Elivon developed into a post office, store, church, cemetery, blacksmith shop and school. When a railroad was built three miles to the south, Elivon dissolved. As the settlers scattered, some of them played a part in Hesston’s emergence as a town. The 1874 Peabody to Grace Hill Church Trail was traversed by a group of Mennonite Christians from Prussia. From Peabody (in Marion County), they crossed Doyle Creek and into Pleasant Twp (in Harvey County). An 1874 Halstead to Hopefield Trail was key to a group of Swiss Mennonite Christians from a Russian province. Leaving the train at Halstead (in Harvey County), they used the Fort Harker Trail to reach an immigrant house west of today’s Moundridge (in McPherson County). Photo credit: https://www.kansasmemory.org/item/305986 2/28/2019.

- Grand Central Station for Trails – Sand Creek at Ninth and Plum in Newton. The Sand Creek crossing in Newton at Ninth and Plum streets was one of the most significant trail sites. It could be said the Sand Creek Crossing was like “Grand Central Station.” The rock bottom made for an easy creek crossing. The site was used by Indian trails and the Abilene/Chisholm Trail, making it the longest used and most heavily traveled site in present day Harvey County. Cattle, horses, chuck wagons, stage coaches and supply wagons crossed here on the way to Abilene, Kansas between 1867 and 1871. 600,000 cattle were trailed to Kansas in 1871, but not all went via the future site of Newton. Several trails were used for herding cattle to the rail heads at cow towns and did not traverse present-day Harvey County. Some herds went on the Middle Shawnee Trail to Baxter Springs, Kansas. Others used the West Shawnee Trail to Junction City, Kansas. Another route used the Shawnee Arbuckle Trail which joined the Abilene/Chisholm Trail in Indian Territory (I.T.) and went north through present-day Newton. Note 1: The rock bottom at the Sand Creek crossing is now gone. Following the devastating flood of 1965, a project to widen and deepen Sand Creek in Newton was undertaken by the U.S. Corps of Engineers. Local historian Dr. Gil Michel witnessed the construction equipment breaking through and destroying the layer of rock which had made this an ideal creek crossing. Note 2: Viewed by looking north at the old 10th Street bridge, the “Old Trail Crossing” goes to the left or west of the bridge. Photo credit: Undated. Collection of Dr. Gil Michel.

- Map Legend – Major Trails in Harvey County, Kansas. Brian D. Stucky, trail finder. Ronald Dietzel, map compiler.

- (A) Humana/Bonilla Expedition of mid 1590s – A Spanish Exploration Trail. An intriguing trail parallels the Little Arkansas River as it cuts across Alta Twp in the northwest corner of Harvey County. This trail has been traced as far as Arkansas City, Kansas. Indicators suggest it might be from the Spanish Humana/Bonilla expedition of the mid 1590s. Consider this: The Spanish government officially sanctioned the Captain Leyva de Bonilla expedition as a punitive operation against the Gavilian Indians in today’s Mexican state of Chihuahua. However, it became an unauthorized enterprise when Bonilla focused on trying to find rumored gold and silver treasure in New Mexico. Between not finding any riches and then hearing about the wealth of “Quivira,” Bonilla’s party traveled eastward into the Great Plains about 1595. Within today’s south-central Kansas, the Humana/Bonilla explorers came to a very large settlement of the Wichita tribe. Not finding treasures, the expedition continued on another several days into the Great Plains. In 1601, Governor Juan de Onate used the input of Jusepe Gutierrez, a survivor of the Bonilla party, to try to locate the Humana/Bonilla explorers, only to learn most of the members had died. Like Bonilla, Onate also found a large Wichita settlement. Some 400 years later, there are strong indications it’s the settlement found at today’s Arkansas City, Kansas. Populated by the Wichita tribe, the city – called Etzanoa – had at least 20,000 indigenous residents. Did the two Spanish expeditions find the same Wichita settlement? Did the Humana/Bonilla group and/or the Onate explorers go through Harvey County as they wandered over the Great Plains? Getting verification from the translated Spanish documents is not definitive since some things match and other things don’t. Thus, more research and documentation is needed. Illustration credit: https://etzanoa.com 11 Feb 2019.

- (B) Cherokee Trail of 1849 – A Gold Rush Trail. With its origins in the 1849 California gold rush, the Cherokee Trail passed through Harvey County. It was also called the “Fort Smith, Arkansas to California Road” as well as the “Evans/Cherokee Trail.” It came out of Arkansas, went through Oklahoma and then into Kansas. Passing through south-central Kansas, the Cherokee Trail joined the Santa Fe Trail east of today’s city of McPherson. From there, it traversed Colorado into Wyoming. The Cherokee Trail connected as a feeder trail to the California Trail and to the California gold fields, becoming eventually an emigrant and all-purpose trail. The trail was shut down at the outbreak of the Civil War. Led by Captain Lewis Evans, the first group on the Cherokee Trail had 130 travelers in forty wagons. The majority were Euro-Americans. About fifteen were Cherokees from Talequah, Oklahoma. They joined the travelers from Arkansas at Grand Saline, Oklahoma. The “Old Branch” (B1) is a portion of the 1849 Cherokee Trail. In 1859, a “New Branch” (B2) developed when interest in the trail was renewed by the Pikes Peak Gold Rush (Colorado Gold Rush). Note 1: The Cherokee Trails of 1849 and 1859 should not be confused with the 1830s era “Cherokee Trail of Tears” during which there was a forced relocation of Eastern Woodlands Indians from the Southeast region of the United States. During the 1830s Trail of Tears, an estimated 100,000 indigenous people (Cherokee, Creek, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Seminole and other nations) were displaced to “Indian Territory” west of the Mississippi River. About 15,000 people died during the journey west. Note 2: Hwy K-15 marker in Harvey County. Photo credit: Ronald Dietzel. October 2018.

- (C) Lt. Col. Morrison Trail of 1857 – A Military Trail. Per reports, “Indian hostilities were harassing a large extent of the surrounding country and Colonel Pitcairn Morrison was ordered out from Fort Gibson with three companies of the Seventh Infantry, numbering 235 officers and men. They left in June and went out over the Santa Fe Trail in Kansas to Fort Mann (Dodge City) and Bent’s Fort, where Morrison held councils with the chiefs of the Kiowa, Comanche, Arapaho, Apache, and Cheyenne Indians.” The general route of the Lt. Col. Morrison Trail was from Fort Gibson in northeastern Oklahoma to a location between today’s cities of McPherson and Inman where it intersected with the Santa Fe Trail; and then through today’s Dodge City to the Bent’s Fort area in southeastern Colorado. The North Branch (C1) of the Morrison Trail came from Butler County, went southeast to northwest through Harvey County and exited into McPherson County. It joined the Santa Fe Trail near today’s towns of Inman and Groveland after which it went through western Kansas and into Colorado. The South Branch (C2) is thought to be an eastward bound return route. It came out of Reno County, went fairly close to where Alta Mill would eventually be built and then took a route along the south edge of Newton’s future site. It exited Harvey County and headed into Sedgwick County. Photo credit: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/18428/pitcairn-morrison/photo 2/21/2019

- (D) Valley of the Cottonwood to Pike’s Peak Trail of 1858-59 – A Gold Rush Trail. An obscure trail, the “Valley of the Cottonwood to Pike’s Peak Trail” paralleled an earlier Kaw Indian trail from today’s cities of Council Grove to Elmdale to Florence and then to the city of Peabody. The route clipped the northeast corner of Harvey County as it went through Walton Twp and Highland Twp. From there, it continued into McPherson County and on west. Possibly a gold rush trail to the Colorado gold fields, it was drawn on early survey township maps in broken pieces from Emporia all the way to Meridian Twp in McPherson County. From that location, other evidence has shown the trail continued until it connected to the Santa Fe Trail at a point southeast of today’s city of McPherson. Note: Hwy K-15 trail marker at Harvey/McPherson county line. Photo credit: Ronald Dietzel. October 2018.

- (E) Black Beaver/Col. Emory Trail of 1861 – Native American Trail Repurposed as a Military Trail. Within Harvey County, the Black Beaver/Col. Emory Trail of 1861 and the Abilene/Chisholm Trail of 1867 roughly paralleled each other. Originally a Native American trail, the Black Beaver/Col. Emory Trail received its name due to an 1861 event which was linked to the outbreak of the Civil War. Some 6,000 Confederate troops were sent from Arkansas to eradicate Union forces in Indian Territory (I.T.; today’s Oklahoma). In turn, Union officials ordered Col. William H. Emory to evacuate Forts Washita, Arbuckle and Cobb. He was to get the Union troops to safety at Fort Leavenworth in northeastern Kansas. To be successful in carrying out its mission, the expedition would be faced with dire circumstances. Escaping to Kansas meant the Union troops would have to cross hundreds of miles of open prairie, which was populated by Native American tribes who were Confederate supporters. To make the escape successfully, a guide would be needed since the route was unknown to the members of the Union expedition. Fortunately for Col. Emory, a Delaware scout named Black Beaver agreed to act as guide and interpreter. Note: Hwy K-15 marker in Harvey County. Photo credit: Ronald Dietzel. October 2018.

- (E) Black Beaver/Col. Emory Trail of 1861. Under the command of Emory, the Union forces quickly moved out of I.T. and into Kansas, going through the future sites of Wichita and Newton. Within present-day Harvey County, Black Beaver guided the 1861 expedition as it traversed just west of today’s Greenwood Cemetery on the east side of today’s city of Newton (whose beginnings were ten years away). The Union force intercepted the Santa Fe Trail near the Cottonwood Crossing at today’s Durham (in Marion County, Kansas) and used it to get to Fort Leavenworth (in northeast Kansas). The column arrived “without the loss of a man, horse, or wagon, although two men deserted on the journey.” Within a few years of the Emory trek, Texas longhorn cattle were trailed roughly along Black Beaver’s path as the cattle were herded along the Abilene/Chisholm Trail. Who was Black Beaver? How was he able to scout the path for Emory’s expedition? Note: Photo is William Hemsley Emory (1811—1887) Photo credit: 6720, Joseph Thoburn Collection, OHS

- Black Beaver or Suck-tum-mah-kway (1806—1880, Delaware tribe). Born in western Illinois, Black Beaver was from the Delaware (aka Lenape) tribe which was originally a Mid-Atlantic coastal people. The Delaware were relentlessly uprooted and forced to move west through Ohio, Indiana, Missouri, Arkansas, Texas, Indian Territory and Kansas. However, they had a long history of allegiance to the U.S. government. As a teenager, Black Beaver trapped and traded beaver pelts for John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company. When the fur trade declined, Black Beaver turned to guiding wagon trains westward. He became one of the most accomplished Native American scouts in North America. He developed his skills as an interpreter, guide, mediator and scout so successfully that his travels and assignments took him to the headwaters of the Missouri River and Columbia River, south to the Colorado River and Gila River and to the shores of the Pacific in southern California. Having lived for a number of years in I.T., he was well acquainted with the Great Plains. Black Beaver spoke English, French, Spanish and eight Indian languages. He could use Plains Indians sign language. He knew how to get around or over obstacles in the terrain, how to determine the easiest crossings of rivers and streams, how to find abundant grass for livestock and how to locate dependable water sources. Photo courtesy National Archives, photo no. 75-ID-118A.

- A Lifetime of Contributions Went Unrewarded. Due to his wide range of skills, Black Beaver was invaluable to the many Euro-American settlers and military expeditions that traveled west. Following his years as a trapper and then as a guide for wagon trains, he served the 1834 Dodge-Leavenworth Expedition as guide and interpreter for Gen. Henry Leavenworth (the military officer whose name was given to the fort, city, county and penitentiary in Kansas) and Colonel Richard Dodge during their councils with the Comanche, Kiowa and Wichita tribes on the upper Red River in Arkansas. In the 1840s, Black Beaver guided an expedition of the naturalist painter John Audubon. During the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), he raised a company of Delawares and Shawnees, leading them as a captain in the U.S. Army. When Cpt. Randolph B. Marcy escorted emigrants from Fort Smith, Arkansas to Santa Fe during the gold rush days of 1849, he engaged Black Beaver as his guide. The resulting trail became the Southern California Road. Thousands of emigrants used this route into southern California. In 1858, it was adopted by the Butterfield Overland Mail and stage line. Black Beaver’s contribution of 1861 in guiding Col. Emory’s party has already been recounted. Due to a friendship with Black Beaver, Jesse Chisholm learned of and used part of the Black Beaver/Col. Emory Trail for what became the Chisholm Wagon Road in I.T. Between 1847 and 1864, Chisholm founded trading posts across I.T. plus one at today’s Wichita, KS. Traversing an existing Indian/military trail, the heavy wagons used to convey supplies between the trading posts caused ruts and soil compaction. This made for a discernible trail. Because Black Beaver supported the Union, Confederates seized his cattle, horses and crops and destroyed his ranch. They placed a contract on his head. Right up until his death in 1880, Black Beaver attempted unsuccessfully to secure promised compensation from the U.S. government for his losses. Note: Item shown is Souvenir map of the Butterfield Overland Mail route. Credit: https://www.okhistory.org 2/28/2019.

- (F) River Route to Cottonwood Falls Trail of 1867. When AT&SF railroad surveyors were staking out a good, reasonable path, they followed an existing wagon trail. It went from Emporia through the future sites of Florence, Peabody, Newton and Hutchinson. From close to Nickerson, it diverted west to the Big Arkansas River and then up to Ft. Zarah (east of today’s Great Bend). By making the southerly bend, wagons (and later, the railroad) were able to bypass the Sand Hills which cover the area from Burrton northward to the Little Arkansas River and then westerly into the area north of Hutchinson. (G) Fort Harker to Wichita (Camp Beecher) Trail of 1868-69. Fort Harker (at today’s Kanopolis) was the furthest west supply post and point of the Union Pacific, East Division. Since no railroad was near Wichita and its small military camp (Beecher), supplies were moved along a wagon trail (previously an Indian trail) from Ft. Harker to Wichita. Fort Harker (originally Fort Ellsworth) was established in 1864 to provide protection for the Kansas Stage Line and military wagon trains transporting goods along the Smoky Hill Trail and the Fort Riley Road. The fort closed in 1872. (H) Fort Zarah to El Dorado Trail of 1871-72. Travelers used this trail as a shortcut to board the train at Newton so they could get back east faster. If they were coming from the Fort Zarah area, travelers diverted from the Santa Fe Trail just southeast of the present-day city of McPherson and angled to Newton. Note: Fort Zarah was established in 1864 as one of a chain of forts built on the Santa Fe Trail to protect wagon trains and guard settlers. During the 1871-72 time frame, there was no Fort Zarah generated activity on this trail since the fort was abandoned in 1869. However, the fort’s former site was a known reference point for travelers so its name was incorporated into the Trail’s name. Source – https://www.kansasmemory.org/item/215797

- Click over to Part B of Unit 3 for cattle trail material. On the map, the cattle trails of Harvey County are marked as (I) and (J).