by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

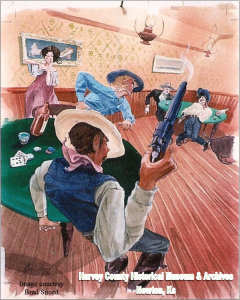

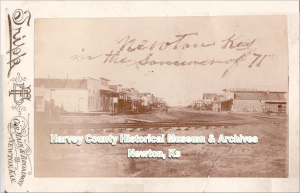

History is full of unanswered questions, strange events and mysteries. One in Harvey County is the identity of the second shooter on August 20, 1871.

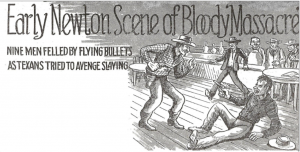

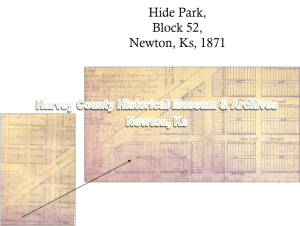

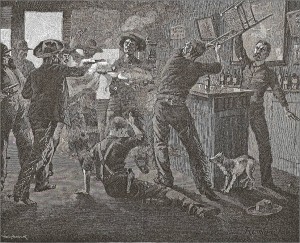

A sensational event in 1871, the community and state were shocked with the level of violence. Perhaps, one of the most notorious gunfights, killing more than at Dodge, yet no one ever claimed credit.

Did the shooter simply walk out the door and into history?

Did he go, change his identity, and live as a law abiding person?

Or did he become a notorious outlaw, but deny this crime? The very mystery has allowed for facts to become obscure and legends to grow.

The area newspapers reported the evening’s gruesome events with relish, but a name is not given to the shooter until later accounts other than “Nemesis” in the article by “Allegro.” Judge RWP Muse was in Newton during the shooting and was the first local person to provide the name “Riley” for the shooter in the 1882 “History of Harvey County”. Judge Muse described the shooter;

“a friend of McCloskey, a boy named Riley, some 18 years of age, quiet and inoffensive in deportment, and evidently dying from consumption . . .”

According to Muse, the young man was known around Newton as “McCluskie’s Shadow.” He was a “thin, tubercular man who followed the railroad gunman around like a little dog that barked and snapped from behind his master.”

Muse theorizes that after witnessing his friend’s death, Riley “coolly locked the door, thus preventing egress, and drawing his revolver, discharged every chamber.” He shot a total of seven men, then, his gun empty, he walked out of the dance hall and was never heard from again. (***see note below)

The first retelling of the events of August 20, other than newspaper reports, took the form of poetry. Theodore F. Price, Dramatic Impersonator, published “Songs of the Southwest” first in 1872 and ten years later a slightly different version. One section of the lengthy poem was entitled “Newton: A Tale of the Southwest.”

The poem identifies the shooter as “Riley.” Price may have gotten this information from Judge Muse, the only other first hand account to use the name.

“What form strides o’er the threshold red

With weapon fiercely clenched?

He looks upon McClusky dead

With gory garments drenched; Then calmly aimed-the trigger drew-

A Texan died-his aim was true. . . .

Seven gory forms before him lying! That friend was fearfully avenged

Grim Riley turned away.”

Over the years exaggerations and errors occurred. In a 1926 article an early settler described the “Newton Massacre” for the Newton Evening Kansan Republican. John L. Wilson recalled that

“the town supported a dance hall at the edge of town. This place was operated by one who went by the name of Rody Joe. The numerous Texas cowboys engaged on the ranches in this section rallied at that favorite resort. One specific instance was pointed out when a man by the name of McClucky invaded the dance hall and shot to death nine Texas cowboys as a result of divided opinions.”

There are several incorrect statements in the Wilson account that only add to the misconceptions and misinformation. Rowdy Joe was a dance hall owner in Newton for a short time before moving to Wichita. In 1871, he was involved in a fatal Newton gunfight with a man named Sweet. By 1873 he was again in the news after a duel with another Wichita saloon owner E.T. “Red” Beard, which was fatal for Beard. Although clearly a violent man, Rowdy Joe was not involved in the shootings on Aug 20. None of the early accounts have McCluskie or McClucky “invading the dance hall.”

The Newton Evening Kansan Republican tried to answer the question of what happened to Riley in a brief article on 4 May 1951 quoting a “prominent citizen of Newton . . .he revealed the story of ‘what became of Riley?’.”

“Law abiding men knew what had taken place [in Tuttle’s Saloon]. They furnished the youth [Riley] with saddle and bridle, a livery stable owner gave him a pony and he rode of town that night and wound up in Ellsworth. . . .Nothing more is heard of him, and it is presumed that his pulmonary disease ended his life.”

Author William Moran noted in Santa Fe and the Chisholm Trail in Newton (1971) that at the time of the shoot out there were several newspaper correspondents in town. Certainly, if Riley could have been found they would have had motivation. Moran theorized that Riley left on the early Sunday morning train, possibly hiding at the east end train yards until the train left. A stow-a-way in the baggage car would not have been noticed. Moran concluded, “Riley could have gone to either Emporia or Topeka, and there taken up where he left off at Newton, that of doing odd jobs under an assumed name.”

Mari Sandoz wrote in 1978, “then as suddenly as he started the slaughter, the youth with the deadly aim cooly stepped out in to the night”. A posse was organized to search for Riley, but he was never seen again in Newton. Some rumors had him “GN” or Gone North; others maintain that he died soon after.

One intriguing theory by cowboy poet Neal Torrey, follows Riley to Nebraska and the Dakotas where he reinvented himself as the famous outlaw “Doc” Middleton. Middleton was a slim blond man of quiet nature who had as one of his many aliases “Jim Riley”.

To answer the question of who was Riley, Kansas historians, Snell and Wilson concluded in an 1968 article for the Kansas Historical Quarterly that “later historians have assigned the given name of James to Riley, but confirming contemporary evidence cannot be found.”

Perhaps a reporter for the Wichita Eagle said it best in an 1957 retelling of the story:

“the final, and perhaps most interesting part of the whole story is, of course, the part played by the unknown youth Riley. He came from oblivion and disappeared into nowhere, but he left his mark on one incident-and on more than one man-in the history of the West.”

One thing is certain, the 1871 season in Newton was lawless and dangerous. McCoy wrote of the 1871 season in Newton:

“A moderate business only was done at Newton, which gained a national reputation for its disorder and blood-shed. As many as eleven persons were shot down on a single evening and many graves were filled with subjects who had “died with their boots on.”

Judge Muse put the number of violent deaths at 12. Later historians, like Drago, state a closer estimate of “sudden death” for Newton during the cattle town years would be 25 – not 50 that some claim. Today, most historians estimate the number dying a “sudden death” during Newton’s cowtown years at 25.

Newton’s General Massacre continues to interest people.

Louis L’Amour used the events of 20 August 1871 in the 1960 novel Flint. The events described in “Crossing” shoot out in the opening chapter is loosely based on the Newton events.

“Legend was born that night in Kansas, and the story of the massacre at the Crossing was told and retold over many a campfire. Of the survivors, neither would talk, but one of the dying men had whispered, “Flint!” It was rumored that Flint was the name of an almost legendary killer who was occasionally hired by big cattle outfits or railroad companies.”

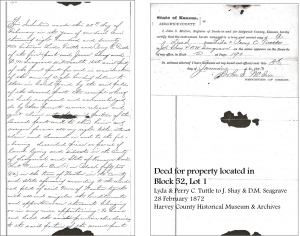

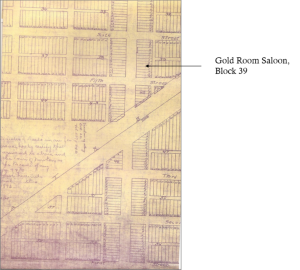

Numerous articles have been written in journals and magazines retelling the story. The facts remain the same. Five men died and three were wounded in Perry Tuttle’s Saloon in the early morning hours of 20 August 1871. One was shot by Hugh Anderson and four by a shooter known as Riley. Following the shoot out, Anderson is transported to Kansas City to recover from his wounds and the second shooter, Riley, disappears.

Sources

- Kansas Daily Commonwealth (Topeka) August 22, 23, & 27, 1871. Recount events of August 1871.

- Abilene Chronicle August 24, 1871. Recount events of August 1871.

- Emporia (Kansas) News August 25, 1871. Recount events of August 1871.

- Newton Evening Kansan Republican. 20 August, 1921; 24 August 1921; 25 August 1921 ; 27 August 1921; 29 August 1921; 30 August 1921; 2 September 1921. 4 May 1951. Microfilm available at the Harvey County Historical Museum & Archives.

- Muse, Judge R.W.P.. A History of Harvey County: 1871-1881. 1882 Harvey County Atlas, reprinted by the Harvey County Historical Museum & Archives. ***Note on Muse’s account: Muse described Riley calmly locked the saloon door, but then Jim Martin could not have left the building. This also relies on the assumptions that a key was in the door and a young man, reportedly not a gunfighter, would have the presence of mind to coolly lock a door. The earliest descriptions of the event hardly give the picture of an accomplished gunman, rather of someone blindly shooting into a dark, smoky room.

- Price, Theodore F. Songs of the Southwest Topeka, Ks: Common-wealth Printing Co, 1872 and 1881.

- Prentis, Noble L. South-western Letters, 1882.

- McCoy, Joseph G. Historic Sketches of the Cattle Trade of the West and Southwest (1874 reprint 1966, on line www.kancoll.org/books/mccoy.htm

- Stewart, C.H. “Newton History” personal recollections written 25 February 1938. (60 years ago-1878) Chisholm Trail Collection, Harvey County Historical Museum & Archives.

- Wilson, John L. Newton Evening Kansan Republican 25 January 1926

.Secondary and On-Line Sources

- Chinn, Stephen. Kansas Gunfighters s.v. http://www.vlib.us/old_west/guns.html.

- Smith, Mark. Gunfight at Hide Park—Newton, Kansas Newton’s General Massacre 19 August 1871 http://www.kansasheritage.org/gunfighters/hidepark.html (accessed October 25, 2007)

- Drago, Harry Sinclair. Wild, Woolly & Wicked: The History of the Kansas Cow Town and the Texas Cattle Trade. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, Inc., 1960.

- Drago, Harry Sinclair. Legend Makers: Tales of the Old-Time Peace Officers and Desperadoes of the Frontier New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1975.

- Hutton, Harold. The Luckiest Outlaw: The Life and Legends of Doc Middleton. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1974. Bison Ed. 1992.

- Miller, Nyle H. & Joseph W. Snell. Why the West was Wild: A Contemporary Look at the Antics of Some Highly Publicized Kansas Cowtown Personalities. Topeka, Ks: Kansas State Historical Society, 1963.

- Moran, William T. Santa Fe and the Chisholm Trail at Newton. ca. 1971 privately printed, Harvey County Historical Museum & Archives.

- Richmond, Robert W. “Early Newton Scene of Bloody Massacre” Wichita Eagle 1957. Harvey County Historical Museum & Archives Historical Files,.

- Rosa, Joseph G. The Gunfighter: Man or Myth? Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1969.

- Sandoz, Mari. The Cattlemen. University of Nebraska, 1978.

- Waltner, John D. The Process of Civilization on the Kansas Frontier, Newton, Kansas, 1871-1873 Masters Thesis, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Ks, 1971.

Articles:

- Dary, David. True Tales of the Old-Time Plains New York: Crown Publishers, 1979.

- Prowse, Brad. “The General Massacre” American Cowboy July/August 1998.

- Sullens, Joe. “Newton, Kansas: the Town the Old West Forgot” True West May 1984.

- Smith, Robert Barr. “Bad Night in Newton” Wild West April 1995.

Fiction & Poetry

- L’Amour, Louis. Flint New York: Bantam Books, 1960. For an interesting discussion on “The Kid at the Crossing” shoot out see: http://www.louislamour.com/novels/flint.htm.

- McArthur, James I. Newton, Kansas Oklahoma: Tate Publishing LLC, 2013.

- Torrey, Neal. “The Newton General Massacre” http://www.cowboypoetry.com/nt.htm.