by Kristine Schmucker, Archivist/Curator

“Man of Mystery at the Rooming House at 7th & Shawnee”

In the early morning of October 31, 1915 a man collapsed on the street near Seventh and Shawnee in Leavenworth, Ks. He was rushed to the county hospital, but he died shortly before 6:00 in the evening that same day. At that time the cause of death was thought to be a result of complicated stomach trouble. The man, known as Frank Thompson, was a stranger in town. No one knew when he arrived in Leavenworth, but he rented rooms at a boarding house at 7th & Shawnee. His age was thought to be around 47 and he was often seen with John Orman, a native of Leavenworth and a retired Kansas City police officer. (Leavenworth Times 1 September 1915)

Two days later, Thompson’s roommate, John Orman died “after an acute illness of a few hours.” Because of the similar nature of the illness that struck both men down, the coroner ordered an inquest.

Both men lived at 7th & Shawnee and were “engaged in the making and peddling of chili.” Orman made the chili. The cause of death was declared to be from ptomaine poisoning as a result of eating chili and no foul play was suspected.

“Chili caused a second mysterious death. John Orman died in great agony in his room at 7th and Shawnee streets.”

Unclaimed Body

Who was Frank Thompson? The paper reported that “no trace of the man’s relatives has been found.” One promising lead came from a family in Nebraska, however after viewing the body they knew it was not their relative. The editor noted that “it is probable that the body will be buried in a local cemetery tomorrow.”

However, there were a few clues. Contact information for Orman’s sister, Mrs. Julia Webber, was found in Thompson’s room with the name Isaac van Brunt. The mystery was finally solved a few days later. Mike Aaron, former guard at the state penitentiary, recognized the body of a former inmate, Isaac van Brunt.

The strangeness of Isaac van Brunt’s death is an interesting story by itself, but his whole life is cloaked in mystery and tragedy with Harvey County connections.

The Orphan Train

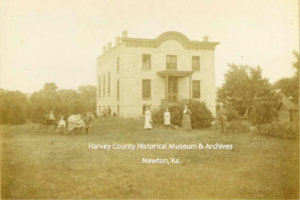

In 1879 or 1880, Isaac van Brunt, a 6-8-year-old boy, stepped off the train in Newton, Ks. He was a long way from where he started as an orphan in Brooklyn, New York. His actual birth date is unknown with a range of 1867 – 1872. Born in Brooklyn, he was possibly the youngest of at least five children born to Albert Isaac and Sarah van Brunt.

In October 1870, his mother Sarah, died and Albert remarried a woman named Hulda. In July 1876, Albert died leaving 8-year-old Isaac with Hulda who did not have interest in raising the child. Isaac was taken to the Children’s Aid Society and placed on a train with 19 other children going west with a stop in Newton, Kansas with the hope of a better life. ***

He was taken to the home of John S. Hackney where he lived until 1884. Later newspaper accounts describe a young boy with “an everlasting propensity for lying and stealing. Mr. Hackney did everything possible to break the boy of his erring way, but to no avail.”

Isaac left the Hackney family only to return after a few years to say that he had reformed. It was not to last. “His was a wandering disposition and he soon left his pleasant home never to return.”

He seemed to shuffle to a number of different places in Harvey and Marion Counties. At one-point, young Isaac met a woman named Mrs. Owens. He boldly asked Mrs. Owens if he could live with her. She no doubt saw a little boy in need and with her husband decided to take him in. Isaac became a close playmate with their daughter Alice. When he was old enough, he began to work as a laborer. Due to moves out of the area by both the Owens family and Isaac, they lost contact with each other.

In 1885, at the age of 15 Isaac was living with Harry Thomas working as a laborer.

Dark Years

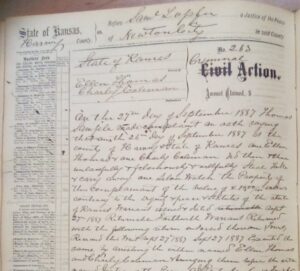

Two years later, Isaac’s life began to go in a bad direction. He was arrested for stealing a watch in August 1887. He spent time in jail charged with burglarizing the home of Harry Turner. He then spent a year for burglary and larceny at Lansing after which he returned to Harvey County.

“Found Murdered!

A Harvey County Farmer Meets with Foul Play!”

On Wednesday morning, May 14, 1890, people in Harvey and Sedgwick Counties woke up to a sensational headline.

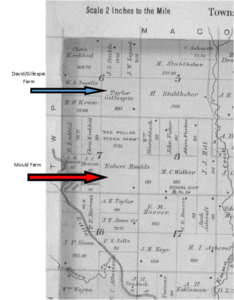

George Broer, a 68 year old farmer in Richland Township, section 26, was discovered dead in his bed. The coroner called for an inquest and the verdict was “that the deceased me his death at the hands of some persons and in some manner unknown to the jury.”

The manner of death was difficult to determine due to decomposition. Strangulation was the prevailing theory. A team of horses, wagon and harness were missing, and a small cupboard where he kept valuables had been “chiseled open and the contents removed.” Broer lived alone and had not been seen since Monday. Clues were scarce.

“Denies Murder”

Law enforcement soon zeroed in on Isaac van Brunt. A reward of $300 was offered by the county, $200 by the Broer estate and $300 by the State for the capture of van Brunt. Sheriff Pollard followed leads from across Kansas from late May to July 4 when he was arrested in Peabody, Ks.

“Marshall W.K. Palmer of Peabody capture Isaac van Brunt who is suspected of having murdered George Broer of Richland township early in May. The officers have been on the track of Van Brunt for a long time.” (Newton Daily Republican 5 July 1890)

On July 4, Van Brunt had been spotted riding through Peabody. Upon his arrest “Van Brunt acknowledged having driven the Broer team away, but denies the murder.”

“Suspected Mischief”

While awaiting trial, van Brunt spent his time in the Harvey County jail where he attempted to escape.

“Sheriff Pollard suspected mischief and yesterday made an examination of Van Brunt’s cell which resulted in his finding the in the bedding a rude saw made from a case knife, a piece from a pair of shears and several burrs which had been removed from the bolts in the jail. . . the county commissioners have now had all the fastenings secured so no more iron can be removed by prisoners.” (Newton Daily Republican, 21 July 1890)

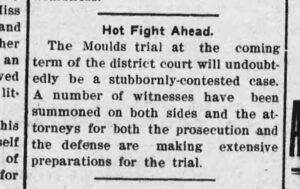

“Trial for the Murder of George Broer – An Interesting Case”

The December 2, 1980 issue of the Newton Daily Republican noted that there was “unusual interest” in this session of the district court “because of the trial of Isaac van Brunt, who is charged with the murder of George Broer.”

All evidence seemed to point to murder with Isaac van Brunt as the culprit. County Attorney Bowman was the prosecutor and he called forty witnesses.

Several testified that they had heard van Brunt confess and that it essentially matched the confession van Brunt had made to the Republican, published in the July 14, 1890 issue. In addition to the confession, much of the evidence against van Brunt centered around his possession of Broer’s missing team and wagon as well as traces of powder found in van Brunt’s case.

The theory put forth, based on van Brunt’s “confession” was that in December 1889, he had supper with Broer. It was then he conceived the idea to murder the man because he had been told Broer had money.

On May 12, he stopped by the Broer farm again and “while Broer was preparing supper Van Brunt stealthily put strychnine in the food. He then fled with his victim’s team and a little money” which was about $4.50. Van Brunt made this confession to the reporter of the Republican.

R.W. Berry and C.E. Branine did their best for the defense suggesting that his confession was influenced by others and that he wa mentally impaired. Two Newton doctors testified on van Brunt’s behalf.

“Drs Axtell and Newhall testified that Van Brunt was of a very low order mentally, and that his disposition was such that he could easily be induced to make statements which would lead to his own crimination.” (Newton Journal 5 December 1890)

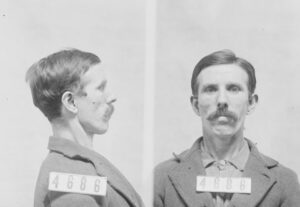

Throughout his life, van Brunt was often described as being mentally impaired in some way. One reporter observed that while “van Brunt evidences little anxiety about the result of his trial his health is becoming impaired.”

Another reporter for the Newton Journal describe van Brunt as a

“man of weak mental make-up, not naturally of a vicious disposition, and his guilt of the crime charged against him is doubted by many. He is perhaps 22 years of age, of slight build and thin, sharp features and shows indication of rapid physical decay. Every few minutes . . . he was noticed to cough like one does in the early states of consumption, his sallow, consumptive complexion, leading one to believe him afflicted with that dread disease.” (Newton Journal 5 December 1890)

Even the reporters, sheriff and county attorney questioned the confession and van Brunt’s mental abilities.

“Sheriff Pollard and County Attorney Bowman are disposed to take Van Brunt’s statement with several grains of allowance. Why since he confesses at all, he should tell any but a straight story it is hard to understand. However he experiences difficulty in traveling the same route twice.”

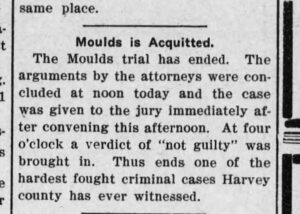

“Guilty of Murder”

After an hour of deliberation, the jury returned with a verdict “guilty of murder in the first degree” (Newton Journal, December 5, 1890)

Once again Count Attorney Bowman was praised by the newspaper, “he conducted the case of the state with rare tact and skill and applied the law with his characteristic gravity and acumen.”

The defense “made as strong a fight as can be made by men without a toothold. Mr. Berry’s address to the jury was very comprehensive and frequently eloquent and pathetic. Mr. Branine, who has a reputation as a good talker, kept up his end.”

“Not Satisfied”

At the sentencing, Judge Houk remarked, ” that he was not satisfied with the evidence produced by the state; that the body should have been exhumed and examined.” Regardless Houk gave the sentence of “a year in the penitentiary and then death by hanging.” (Newton Daily Republican, 29 December 1890)

“Pardon for a Forgotten Man”

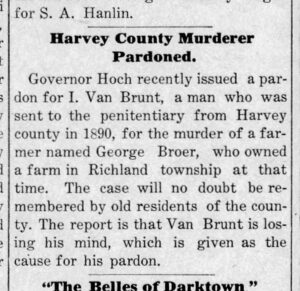

Isaac van Brant’s story did not end in a hanging. For seventeen years, served his sentence at Lansing as a model prisoner. He received no visitors or mail. He was very much a man alone in the world.

One person remembered him, a long-ago foster sister named Alice. For fifteen years, Alice Owens Bertenshaw had been looking for information on her childhood friend. Completely by chance, she learned of his imprisonment at Lansing for murder. Alice wasted no time in visiting Isaac. She shared the distressing story with Kansas Gov. Edward Hoch. The story of this friendless man “touched the chief executive’s heart” along with lingering questions about van Brunt’s guilt.

In addition to pardoning Isaac van Brunt, the governor made several visits to the penitentiary “to see prisoners who are alone, friendless- for whom no hand reaches out in help.”

The reporter for the Leavenworth Post described van Brunt’s release.

“The man who had spent so many years in prison seemed more like a child and had no dependence upon himself. When he was given his money for his years of servitude he turned and passed it to Mrs. Bertenshaw, remarking, ‘You take it. I don’t know what to do with it.”

Following the pardon, with Alice’s help, van Brunt moved to a farm near Independence, MO. Eventually he made his way to Leavenworth, Ks. He died alone on October 31, 1915.

Even with the pieces of his story put together, Isaac van Brunt remains a solitary man of mystery.

Sources

Primary Sources

- Newton Kansan: 11 August 1887, 14 May 1890

- Newton Daily Republican: 21 January 1890, 21 June 1890, 5 July 1890, 9 July 1890,14 July 1890, 5 2 December 1890, December 1890, 29 December 1890.

- Newton Journal: 21 February 1908.

- Sedgwick Pantagraph: 10 July 1890, 24 July 1890, 27 February 1908.

- Wichita Daily Eagle: 14 May 1890, 16 July 1890, 6 December 1890,

- Evening Kansan Republican: 3 September 1915; 31 December 1915.

- Leavenworth Times: 12 February 1908, 9 September 1915.

- Leavenworth Post: 31 August 1915, 1 September 1915, 2 September 1915, 3 September 1915.

- St Louis Globe: 5 February 1908.

Secondary Sources

- ***Halfide, Lori, “Revisiting Isaac” Head of Research, National Orphan Train Complex, Concordia Ks, 2023. The information for Isaac’s early life comes from research completed by Lori Halfide.