by Kristine Schmucker, Archivist/Curator

Earlier this week, Wendy Nugent, reporter for the Harvey County Now, sent me a message asking if I knew anything about a man named Scott Owens. His tombstone in Greenwood needed repair and she was doing a story on it with Sylvia Kelly. Turns out, there was an interesting story about a Harvey County family.

The first thing to clear up was the mystery of his name. In the Greenwood Cemetery register he is listed under the name of Scott Owen Faulkner. Other Faulkners listed include Laura and Charles. How did these people fit together? Or did they?

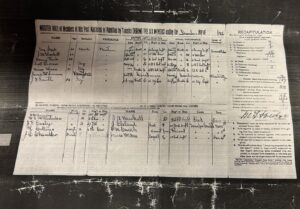

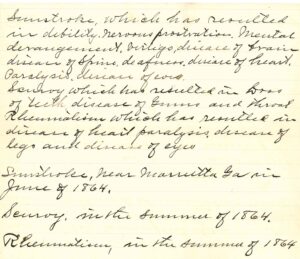

One document from 1901 lists a Scott Owens, born in Kentucky living in Newton. The document is a muster roll and he is listed as entering the army May 5, 1864 as a private Co. D 15th U.S, Col Inft, and discharged in August under General Order. The year of discharge is difficult to read. It might be 1865?

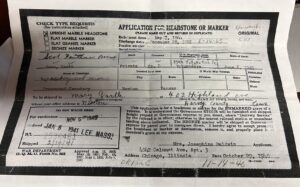

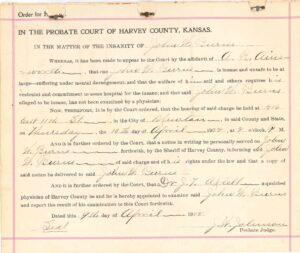

To add to the confusion, his daughter lists his name as Scott Faulkner on the order form for the tombstone and lists the discharge date as December 28, 1891.

The obituary for the man that died on June 6, 1935 is identified as John S. Faulkner or John Scott Faulkner, even though the Greenwood Register lists Scott Owen Faulkner. It seems that Scott Owen Faulkner is the same person as John S. Faulkner. When and why did he change his name? Who was Scott Owen Faulkner?

There is no listing or census record for a Scott Owen Faulkner living in Harvey County, Kansas. There is however, plenty of evidence of a John Scott Faulkner living in Newton.

Pioneer Resident

According to the Newton city directories and the census, a man by the name of John Faulkner had been living in Newton for sure since 1885. The obituary for John S. Faulkner noted that he had been a resident of Harvey County for 55 years, so he likely arrived in 1880. It is possible he came, along with his wife and young daughter, with a larger group that included Katie and Wilson Vance, Willis and Emily Brooks, Frank C. Childs, Madison Thomas and Abe Weston.

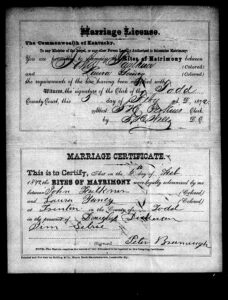

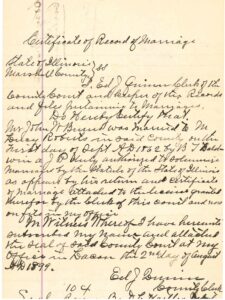

J.S. Faulkner was born in 1849 in Virginia very close to the Kentucky boarder. He enlisted in the Civil War in May 1864. He married Laura Yancey February 6, 1872 at Trenton, Todd County, Kentucky.

The couple came to Newton around 1880 with 4 year old Mary. Their next child, Charles, was born in Kansas in 1881. Johanna was born in 1884. In the Newton city directories for 1885 and 1887, John is listed living at 129 S 2nd with the occupation of mason. By 1911, the Faulkner family is living on W 1st and in 1917 the address of 912 W 1st is given.

“Colored Civil War Veteran”

Further clues come from his and Laura’s obituaries.

John’s obituary noted that with his passing “only five comrades who saw service in the war between the states remain in Newton.” He is likely one of the unidentified Black men in this photograph taken in front of the Harvey County Courthouse.

Faulkner was described as “a stout patriot, devoted churchman,” and seems to have led a quiet life. His name does not appear in the Evening Kansan Republican except for Laura’s obituary and his own.

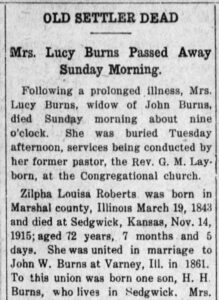

Laura Yancy Faulkner was born in 1856 in Kentucky, probably Todd County. After her marriage she is a quiet presence. For some reason, her name is not listed as a wife of John’s in the city directories until 1917 although the census’ clearly have her living with him. She died at her home at 912 W 1st on June 25, 1930, from pneumonia. She had been ill for some time.

John died five years later also in the month of June on June 6, 1935. He was survived by his three children Mary Faulkner Garth of the home; Josephine Faulkner Baldwin, Chicago; and Charles Faulkner, Newton; seven grandchildren and two great grandchildren. His services were held at the C.M. E. Church in Newton with Rev. C.V. Williams officiating and the Women’s Relief Corp assisting.

Faulkner Children

Son, Charles, worked as a porter and baggaman for the AT&SF. He and his wife, Georgia, also lived at 912 W 1st until the 1930s when they are listed at 119 Elm. Charles died August 13, 1937, at the age of 57.

In 1941, daughter, Josephine* Baldwin ordered a headstone for her father from the government to be delivered to her sister, Mary Faulkner Garth, who was living at 402 Highland, Newton. Up to that point his grave may have been unmarked and as a veteran he was entitled to a headstone. This is the headstone that Sylvia Kelly hopes to repair.

*All other sources refer to her as Johanna or Joanna.

Additional Note:

During this same time period, there was a white Faulkner family, J.M. and Laura Faulkner. They lived at 325 W 8th, Newton and had at least two children, Olin and Fern. J.M. Faulkner worked for a time as an assistant Marshall and their names appear frequently in the Evening Kansan Republican. They left Newton at some point and are not buried in Greenwood Cemetery.

Thank you

to Sylvia Kelly for calling attention to John Scott Faulkner’s tombstone and to Wendy Nugent for being curious. Nugent’s article, “Kelly Wants To Straighten Out History” is in the Harvey County Now August 21, 2023 issue.

Sources

- Evening Kansan Republican: 7 June 1935

- Newton City Directories: 1885, 1887, 1902, 1905,1911, 1913, 1917, 1919, 1931, 1934, 1938.

- Kansas Census: 1895

- U.S. Census: 1900, 1910, 1920, 1930

- Greenwood Cemetery Register of Burials, Harvey County Historical Museum & Archives, 203 N. Main, Newton, Ks.