by Kristine Schmucker, Archivist/Curator

People of Harvey County

Abe Weston, Jr was a character that kept the police, courts and newspapers on their toes for several years in the late 1890s. He frequently appears in the Police Reports in the Newton Kansan for anything from a knife fight to drunk and disorderly. At one point the editor of the Newton Kansan dryly observed that Westons were “not the most peaceful people on earth.” (21 October 1897) In addition, his interaction with the “White Caps” help tell the story of a little-known organization in Harvey County.

Idlewild, Kentucky to Harvey County, Kansas

Abe Weston, Sr was born a slave, probably around 1819 in Kentucky.**** His final owner, and possibly only, was Col. Elijah Sebree. The plantation home of Col. Sebree still stands near Trenton, Ky. Built in 1830, the property is called Idlewild. Sebree was a prominent landowner, tobacco and cotton trader, coal mine owner and railroad builder.

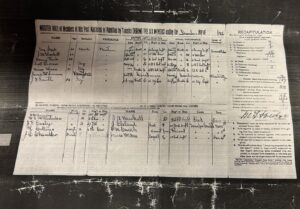

In 1880, a group of thirty-one former slaves from Col Sebree’s planation came to Harvey County, Ks. Among them was Abe Weston, his wife Mariah, and children Frank (4), Stephen (8), John (17) Matilda (13) and Abe Jr (10). Abe Weston, Sr died in 1902 at the age of 83. In his obituary, there is no mention of his wife, only his five children. Not much more can be gleaned from the newspapers about him.

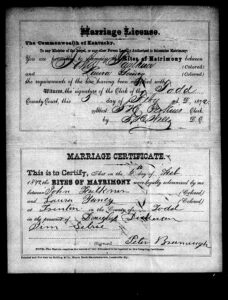

Abe Weston Jr was born in 1870 in Kentucky and came to Kansas with his family in 1880. At some point he married a woman named Florence who went by the nickname Flossie.

In 1888, Abe Weston, Jr begins to appear in various newspaper notices. In January 1888, Abe Weston, 18, was involved in organizing a baseball team along with O.L. Boyd, C. Colman, John Roston, Wm Richman, Chas Fox John McClain, A.J. Tandy, W.A. Brown and Mike Vance. (Newton Daily Republican 27 January 1888).

He was involved in a disturbance in 1888, when he was arrested and appeared before Judge Spooner. His fine was $7.50 and costs. (Newton Daily Republican, 19 October 1888) For five years all was quiet, however, in 1893, both he and his wife appeared in Police Court. Abe was convicted of disturbing the peace. He paid his fine of $5. Mrs. Abe Weston also appeared but her charges were “dismissed on account of the incompetency of the complaining witness.” (Newton Daily Republican, 23 December 1893)

More Sinned Against than Sinning’

The Weston family often had squabbles among themselves that led to injury and an appearance in court. The October 21, 1897 Kansan reported difficulty between Abe and his wife Florence, brother Frank and Klan Rossiter ending in Florence being beaten. The next morning, Mrs. Florence Weston “swore out a warrant” for Abe’s arrest, along with Frank and Rossiter. Abe disappeared. Frank Weston and Rossiter appeared before Police Judge von der Heiden who “after gravely surveying the belligerents through his judicial specs, concluded that Flossie was more ‘sinned against than sinning’ and let her go.” He fined both Frank Weston and Rossiter $5 and costs. (Newton Kansan 21 October 1897)

At that time, the Newton Daily Republican described Abe Weston as “a colored citizen of Newton, ever ready to fight the first man who looks crossed-eyed at him.” (Newton Kansan 21 October 1897)

Perhaps the gravest incident involved some “difficulty in the alley back of Murphy Bros restaurant . . . in which Weston cut (Nate) Rickman with a knife quite severely.” (Newton Kansan 24 December 1896) According to Weston’s statement at the preliminary hearing “Rickman had stayed with Mrs. Weston the night before and that he went around to talk to him about in a gentlemanly way.” According to Weston, Rickman started the fight. (Newton Daily Republican 17 December 1896)

According to Rickman, Weston called him out in the alley regarding Mrs. Weston. Rickman could not abide by the names Weston was calling him, so he struck Weston who then came at him with a knife. He then went after his gun and shot at Weston. Rickman pleaded guilty to assaulting Weston and paid the fines. Weston was sentenced to jail.

Abe Weston released from jail with several others on April 15, 1897 (Newton Kansan, 15 April 1897)“on the condition they behave themselves.”

“Knocked from the Top of a Moving Train”

One of the last times Abe Weston appears in the Newton papers is in February 1900. According to the newspaper, Weston suffered a serious train accident while on the job as a porter for the Santa Fe. Part of his job was to “climb to the top of the blind baggage car” to look for bums “who usually jump the train when it is well down in the yards going east.” As train passed the 2nd street viaduct, “Weston, forgetful of the danger over head, sat in an upright position, and was knocked from the top of the moving train.” He fell to the tracks resulting in a broken leg and “hurting himself about the head. . . the physicians in charge stated nothing serious would result.” (Evening Kansan Republican, 27 February 1900). After this accident, he must have moved from Newton. In his father’s 1901 obituary it lists his residence as Kansas City. Hopefully to lead a more peaceful life.

Perhaps the most interesting is that Abe Weston was quoted, verbatim, in the Evening Kansan Republican. In the fall of 1896, Weston was involved in some activities that caught the attention of a little-known group in Harvey County – the White Caps.

“We Will be Here Tonight!”

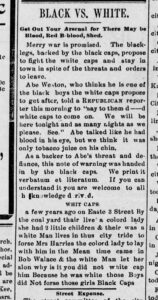

On April 4, 1896, Abe Weston issued a challenge to the White Caps in response to their warning to leave town. He told the editor of the Newton Kansan to “say to them d–d white caps to come on. We will be here tonight.”

Weston then gave the reporter a notice from the “black caps” which the paper printed verbatim.

“A few years ago on Easte 3 Street by the coal yard thair live a colord lady she had 2 little children & their was a white Man lives in thus city tride to forse Mrs. Harries the colored lady to lay with him. in the Mean time came in Bob Walace & the white Man let her alone. why is it you did not white cap him? Because he was white. those Boys did Not force those girls. -Black Caps”

What was the reason for this challenge? At the end of January 1896, there was an incident that was upsetting to many in the Newton community. According to reports, for several weeks a group of young men “occupied” rooms in a building “within a stone’s throw of the Santa Fe station.” It was observed “that there were supposedly respectable white girls enamored with colored young men of the city; that these girls and young men had been in the habit of going together and that to all appearance were in love with one another.” Everything came to a head one weekend when they held a “high carnival until the following Monday night. Refreshments were provided in abundance, including liquid beverages and after dinner cigarettes. It is to be presumed that the four couples let joy be unconfined and made the weekend ring with their hilarity.”

This event came to the notice of people who were “appalled. . . Notices were accordingly drawn up in true White Cap style, signed in red ink, supposed to be blood, and profusely decorated with gruesome skulls and cross bones.” The four young men were warned that they would be tarred and feathered if they did not leave town. They did leave town.

As long as they stayed away, all would be well. The editor noted that the White Cap organization “has taken upon itself the purification of the town so far as these scandalous proceeding are concerned.” On April 3, 1896, two of the young men returned to Newton. The White Caps notified them “to seek other climes or take the consequences, which will probably be tar and feathers or a rope neck tie.” (Evening Kansan Republican 3 April 1896)

The next day, Abe Weston issued the challenge on behalf of the “black caps” that was printed in the paper.

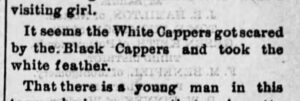

From the newspapers nothing more was reported. On April 8 a small note appeared on the front page “it seems the White Cappers got scared by the Black Cappers and took the white feather.” Noting more could be found about this incident.

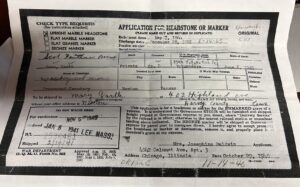

Abe Weston died in 1930 in Kansas City, MO. His occupation is listed as train porter.

Who Were the White Caps?

In his statement to the paper, Weston reminds people of an incident that happened a few years ago to a Black woman and wondered where the White Caps were then? He was right in asking the question.

Find out more about this group and their activities in Harvey County in our next post.

**Based on the 1880 U.S. Census his birth date would be 1832.