by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

The 1880s in Newton were filled with optimism and incredible growth. Main street was filling in with buildings and new businesses. Businessmen were busy with real estate and building a modern progressive city. They were eager to push away the reputation of the 1870s and “Bloody Newton” and replace it with “Progress and Prosperity.”

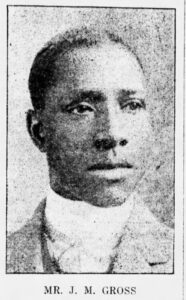

Perhaps this thriving community was what drew thirty-one year old James M. Gross and his wife, Frances, to Newton in approximately 1884* to establish a barber shop. No doubt James and Frances were also looking for a good place to raise a family. The couple’s first child, Carl J., was born on October 7, 1885 in Newton. By 1888, James had joined his brother, George, in the barber shop business. Throughout the next thirty-three years both James and Frances were active leaders in Newton’s “colored” community.

James & Frances Gross

James was born on December 25, 1866 near Lexington, Mo. In 1883, he moved from Missouri to Ottawa, Kansas where he learned the barber’s trade. Perhaps to apprentice, he spent a year with Dan Lucas of Kansas City. Once in Newton he worked with his brother for a number of years. By 1900, he was the sole propietor of the barber shop and the Evening Kansan Republican noted, “he has made his business a financial success.” and is known as a “progressive Kansan.”

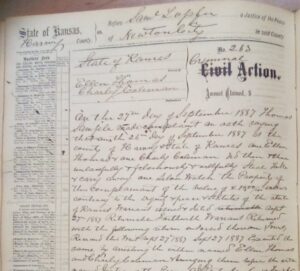

James M. and Frances Gross were married 12 June 1894 in Buchanan, Missouri.** Frances also known as Fannie was born in 1863 in Christian, Kentucky, to Loyd and Melonia Clements. Frances was previously married to a man named Ben Morrow.

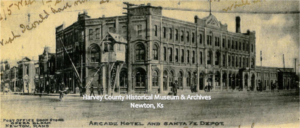

Arcade Barber Shop

In Newton, James opened his own barber shop in the newly rebuilt Arcade/Santa Fe Depot building in May 1900.

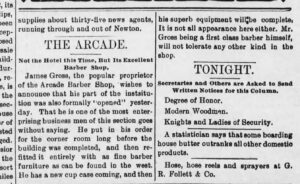

Always looking for ways to impove his services, in the spring of 1901, Gross annouced that he had “added an adjustable chair for children to his barber shop.” At the state level he had the respect of both Black and white barbers. Gross was a charter member of the Kansas State Barber’s association No. 6 of Newton. The organization had a membership of twenty, seventeen of whom were white. He was elected treasurer and later, secretary for the organization.

Both the Evening Kansan Republican and the Topeka Plaindealer agreed; James “conducted the leading tonsorial parlors of the city . . . he is held in the highest estem by the businessmen of his town.”

“One of the Leads in Society”

Both James and Frances were active members in the Black community, locally and at the state level. James was a writer for the Topeka Plaindealer, a newspaper run for and by the Black communities in Kansas and printed in Topeka.

Locally, he was active in the local Fred Douglas literary society, serving as president in 1900. The group of men met to discuss various issues of concern or interest to them. At their December 1900 meeting, papers were read and then a discussion was held on the topic, “That the Negro has a better right to this country than the Indian.”

Frances was described as “his cultured wife . . . one of the leads in society and church circles” with her “winning way and sweet disposition.” She also was involved in several local women’s group including N.U.G, which seemed to function much like the all white Ladies Reading Circle, Unic Octon Club, and the Colored O.E.S. Almond Chapter 27 where she served as Worthy Matron in 1920-21.***

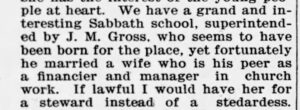

Both James and Frances were heavily involved in their church. At a benefit in 1902, James “made a fine Uncle Rufus or ‘Ole Man’.” A short time later, the paper reports that James’ performance of I’ve a Longing in My Heart for You “brought the house down.” He also served as Sabbath Superintendent for the A.M.E. Church.

Frances apparently also had a mind for business and the Topeka Plaindealer, May 1901, noted she was James’ “peer as a financier and manager in church work. If lawful I would have her for a steward instead of a stewardess.”

“A Delightful Lawn Party”

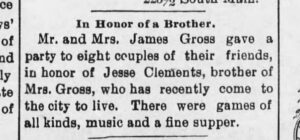

The couple frequently entertained in their home. In April 1900, they held a welcome to Newton party for Frances’ younger brother, Jesse, which included games, music and “a fine supper.”

Later that same year, they hosted “a delightful lawn party” for their out-of-town guests, P.J. Morrow and his wife, at their home on east 4th. “Excellent music was furnished by Messrs. Hamilton and Robinson of Wichita and it was of a very high order.” Morrow was likely a relative of Frances’ first husband, Ben Morrow.

“Most Prominent Colored Citizen”

In 1909, James sold the Arcade barber shop to G.A. Tong. In the announcement to the paper, he noted he plans to remain in Newton, but wanted to make a trip to the Pacific coast. In July 1909, he accepted a position as a Pullman porter. His “run” was between Newton and Amarillo.

James and Frances were living at 511 east 8th with their son, Carl and his wife Canilla Gross in 1918.

One year later the Evening Kansan Republican on May 16, 1919 carried the sad announcment that at 3:30 in the afternoon James Gross, “one of the most prominent colored citizen of Newton” had died from stomach cancer.

He is buried in Greenwood Cemetery, Newton, Ks.

Describing James M. Gross, the Topeka Plaindealer noted; “He was well respected by all who know him as a man devoted to his family and race.”

Notes

*Gross’ Obituary gives the date 1897 for his arrival in Newton. This is likely an error in printing, as census and newspapers have the family in Newton Ks by 1885 when Carl was born.

**Frances Clements Morrow Gross was previously married to a man named Ben Morrow. Some of his children also came to Newton at the turn of the century.

***In 1925-26 Carl J. Gross family moved to California and established a life there. There is no mention of Frances in the Newton papers after 1921. The location of her burial has also not yet been discovered.

Sources

- Evening Kansan Republican: 1 May 1899, 12 Jan 1900, 15 May 1900, 25, 12 Dec. 1900, 29 April 1901, 9 Jan 1902, 4 Mar 1902, 8 April 1902, 17 May 1902, 23 July 1902, 1 September 1902, 18 Aug 1903, 26 Aug 1903, 29 Aug 1903, 18 Aug 1905, 25 May 1909, 30 July 1909, 16 May 1919, 5 Feb. 1920, 29 June 1921, 29 Dec 1921.

- Newton Journal: 23 May 1919.

- The Topeka Plaindealer: 1 June 1900, 2 Dec 1900, 1 Mar 1903, 13 Nov 1903, 29 July 1904, 2 Oct 1904, 3 Oct 1904, 2 Dec 1911, 2 Feb 1912, 9 Feb 1912 13 December 1912, 3 March 1916, 4 April 1919, 16 May 1919, 30 May 1919, 31 Oct 1919.

- U.S. Census: 1870, 1900, 1910, 1930, 1940.

- Kansas Census: 1915

- Marriage Certificate for James M. Gross and Fannie B. Morrow, 12 June 1894, Missouri, County Marriage, Naturalization, and Courthouse Records, 1800-1991.