by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

August 20 marks the date of one of the most violent days in the history of Newton, Kansas. One hundred and forty-three years ago, “Newton’s General Massacre,” captured the attention of the nation and gave the new town the reputation as “Bloody Newton.” The events of the early Sunday morning hours of Aug 20, 1871 are still the subject of questions, books, and even, a screen play. Our next three posts will feature the event that gave early Newton such a bad reputation.

In the 1870s there was a saying . . .

“There is no Sunday west of Newton . . . and no god west of Pueblo.”

In the opening paragraph of the “Newton” section in his History of Harvey County, (1881) Judge RWP Muse wrote,

“It is an old saying, that a bad beginning insures a good ending, and if this be true, then will the infamous character, which the town justly earned, in the early days, fore-shadow an after career of unexampled greatness and prosperity”.

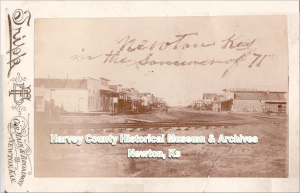

During the summer of 1871 Newton seemed to go up over-night around Joseph McCoy’s stockyard. A cowboy passing through provided this description of the new town.

“We crossed Bluff Creek into Kansas and passed Newton during the latter part of May. A blacksmith shop, a store, and a dozen dwelling places made up this town at that time, but when we came back through the place on our return home thirty days later, it had grown to be quite a large town, due to the building of the railroad. It did not seem possible that a town could make such a quick growth in such a short time, but Newton, Kansas sprang up almost over night.” (Waltner, p. 14 quoting J. Marvin Hunter, ed. The Trail Driver of Texas, Vol. I p. 369)

The first passenger train arrived in Newton on July 17, 1871. Judge Muse and R.M. Spivey opened a land office and aided in constructing wood structures with false fronts and awnings along Main Street. The new town soon had it’s share of businesses that catered to the “cow-boy” along Main Street including grocers, clothing and entertainment.

A reporter for the Wichita Tribune (24 August 1871) observed that Newton had ten bawdy houses

“in full running order and three more underway. Plenty of rotten whiskey and everything to excite the passions was freely indulged in . . . Rogues, gamblers, and lewd men and women run the town.”

Henry Lovett’s 1st Saloon, opened in the Spring 1871, and was located at the northwest corner of 4th & Main and the O.K. Saloon was located on 5th Street with two additional “houses” located east of the OK. One writer claimed that every third building was a saloon.

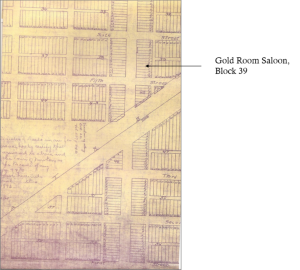

The Gold Room, owned by future Newton mayor James Gregory, was located between 5th & 6th on Main and was considered the “grandest.”

Described by a Topeka Commonwealth reporter, the Gold Room Saloon was a large, roughly constructed, frame building. Inside, a twenty foot bar was left of the front door. Barrels containing all kinds of liquors and wine were behind the bar. The “mantle or show part of the bar, lined with clusters of decanters daintily arranged and polished until their shimmer is like that of diamonds” was above. Opposite the bar, were the gaming tables. A raised platform for entertainers was at the rear. (Topeka Commonwealth, September 17, 1871).

In general, saloons in Newton had been constructed quickly. They were often were long, narrow rooms, darkly lit, with small, not very fancy bars. Kerosene lamps provided a yellowish light; everything was smelly and dirty.

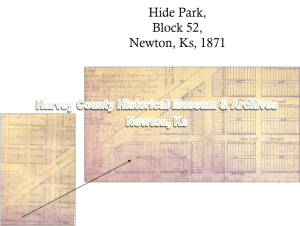

In addition to the Main Street saloons, there was an area south of the AT&SF tracks known as Hide Park “because the girls showed so much of their hide.” ** The two largest and best known were the saloons were owned by Perry Tuttle and Ed Krum and located in the “red-light district,” otherwise known as Hide Park.

Tuttle’s was more popular, all through the night, Sundays included, there was activity.

Law enforcement in Newton was uncertain. The new town had to rely on township authorities from Sedgwick or special policemen hired by the saloon owners.

The Topeka Commonwealth observed one “of the constables and the deputy sheriff have been appointed policemen. They receive their pay from a fund raised by the gamblers.” Fights were not uncommon.

Long time resident C. H. Stewart recorded memories of his boyhood in Newton during the mid-1870s. He recalled that there were “many cow-boys in town who frequented the saloons . . . And the ‘boys’ would get drunk and come staggering along those walks with their jingling spurs and clanging boots and wild whoops”. (C.H. Stewart, “Newton History” )

Into this environment of lawlessness comes the Texas cowboys, many of whom sided with the Confederacy during the Civil War, and northern veteran businessmen looking for a new start. The two groups mixed together on the streets and in the saloons with sometimes tragic results.

Several well-known gunfighters came through the area during July and August. John Wesley Harden, one of the most notorious Texas gunfighters, had followed the Chisholm Trail in 1871 on a cattle drive and spent time in Newton. Billy Brooks also was in and out of Newton as law enforcement and as gunfighter depending on the situation in the early 1870s.

- Billy Brooks

- John Wesley Harden

Trouble started early. Muse reported:

June 15, 1871 Snyder shot and killed Welsh in front of Gregory’s saloon. Both were “cow-boys”. A few days later Johnson killed Irvin in the Parlor Saloon. His pistol was accidentally discharged, the ball passing though a partition and killing Irvin. . a man of no known character.”

August was the peak of the cattle drive season and all the ingredients were in place for violence. Muse described the atmosphere;

“About the first of August, a young man, named Lee was shot and killed in one of the dance-houses in Hyde Park, accidentally. . . Newton was indignant over the murder of a young cowboy named Lee.”

Lee was well liked, handsome and outgoing with many friends “but the citizens of the town were helpless before the fierce, gun-totting Texans” and the incident was ruled an accident.

Ten days later another shooting.

Mike McCluskie, an Irishman from Ohio, also known as Arthur Delaney or Art Donovan, was in town. He had a rough reputation and was described as “among the hardest individuals to ever walk Newton.” Previously he had worked for the Santa Fe Railroad as a night policeman. In August 1871, he was hired by the Newton authorities as a Special Policeman to help keep order during the railroad bond election on August 11.

“Billy” Bailey, a Texan, described as a “thoroughly offensive and officious” gambler. It was rumored that he killed at least two other men in gun fights. Bailey was also hired as a Special Policeman for the elections. The two men, McCluskie and Bailey, had a long standing feud, possibly over a woman, which came to a tragic conclusion August 11, 1871.

August 11, Friday – Election Day

During the day, McCluskie and a drunk Bailey argued. Later, at the Red Front Saloon, the argument escalated into a fistfight. Bailey left the saloon with McCluskie following, guns drawn. Two shots were fired at Bailey, who died the next day. McCluskie, realizing he is in danger from Bailey’s Texas friends, left for Florence by a train.

August 19, Saturday

A week later, feeling the danger had passed, McCluskie returned to Newton and went to Perry Tuttle’s Hide Park Dance Hall to gamble.

August 20, Sunday Morning

1:00 a.m. Apparently, sensing trouble, Perry Tuttle attempted to close the dance hall. Customers refused to leave, even after the band left.

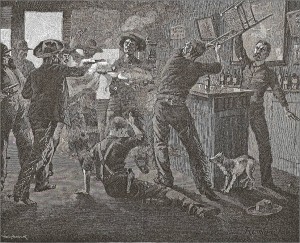

2:00 a.m. McCluskie remained at the faro table. Three Texans, Billy Garrett, Henry Kearnes, and Jim Wilkerson, entered the dance hall, one joined McCluskie at the faro table. A short time later a Texas cowboy, Hugh Anderson entered, gun in hand.

Anderson was the son of a wealthy Texas cattleman, and was in Kansas working as a cowboy in August 1871. He had recently ridden with John Wesley Hardin and had been part of a brutal killing of a Mexican cowboy earlier in the summer. Now his mind was on revenge for the death of his friend Bailey. McCluskie’s return to Newton on Saturday was Anderson’s opportunity.

The Emporia News described the next few minutes inside Tuttle’s Dance Hall.

Anderson walked directly to McCluskie, “with murder in his eye, and foul mouth filled with oaths and epithets, he steps up to McCluskie and shot him,” striking him in the neck. Mortally wounded, McCluskie fell to the floor while attempting to fire his own pistol, which misfired. This account goes on to note that “shooting then became general” ending with five men killed and three wounded. (Emporia News, 25 August 1871)

Next week: “The Full and Graphic Account” Newton’s Bloody Sunday Part 2 Several reporters were in Newton to cover the cattle drive and the provided their readers “back East” with detailed accounts of the “Wholesale Butchery” that occurred in Newton, Ks on August 20.

Links to other posts.

- Part 2,

- Part 3

- Carlos B. King

- Hugh Anderson, Part 1

- Hugh Anderson, Part 2

- Hell Upon Earth: Hide Park

**Note: Hide Park has also been spelled “Hyde Park“. Muse used “Hyde“, but other contemporary sources used “Hide.”

Sources

Maps:

- Plat of the Town of Newton, Ks, 17 August 1871. Map Collection, HCHM Archives.

Newspapers:

- Topeka Commonwealth, September 17, 1871.

- Emporia News, 25 August 1871

Accounts:

- Muse, Judge RWP. History of Harvey County, (1881) Harvey County Historical Museum and Archives, Newton, Ks. First published in Edwards, John P. Historical Atlas of Harvey County, Kansas. Philadelphia, 1882.

- Stewart, C.H. “Newton History” February 25 1938 recalling 60 years ago (1878). Chisholm Trail Collection, HCHM Archives.

- Hunter, J. Marvin, ed. The Trail Drivers of Texas. 2 Vols.

- McCoy, Joseph G. Historic Sketches of the Cattle Trade of the West and Southwest, 1874.

Secondary Sources:

- Davis, Christy. “Rediscovering Newton: An Interpretive Architectural History” Master’s Thesis, WSU, 1999.

- Drago, Sinclair Wild, Wooly and Wicked: the History of the Kansas Cow Towns and the Texas Cattle Trade. New York, 1960.

- Dunlap, Great Trails of the West, New York: Abingdon Press.

- Miller, Nyle and Joseph Snell. Why the West Was Wild. Topeka, Ks 1963

- Streeter, Floyd B. The Kaw: Heart of the Nation. New York: Farrar and Rinehart, 1941.

- Waltner, John. ‘“The Process of Civilization on the Kansas Frontier, Newton, Kansas, 1871-1873” MA These, University of Kansas, 1971.

This three part blog series is adapted from our Speaker’s Bureau Program, “Newton’s Bloody Sunday.” For more info on our Speaker’s Bureau and programs available see: https://hchm.org/speakers-bureau/