by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

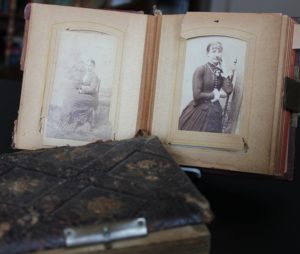

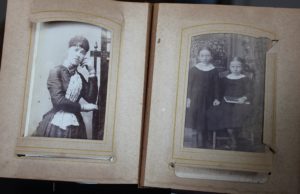

The first school in Harvey County was established in Sedgwick, Kansas in September 1870 with C.S. Bullock and his wife as teachers. We do not have a great deal of information on early schools in Sedgwick, however, looking through photos I came across a collection entitled; “The Giddy 8 of ’98.”

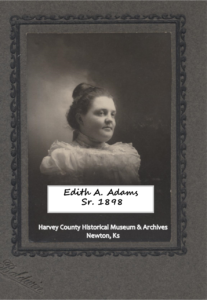

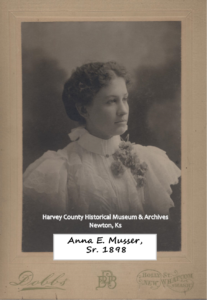

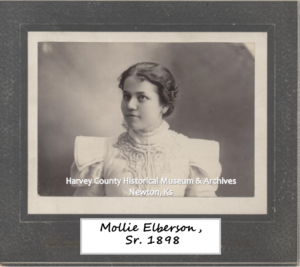

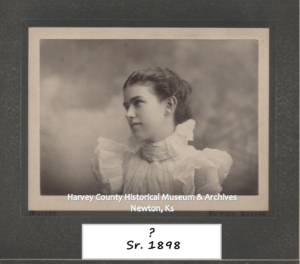

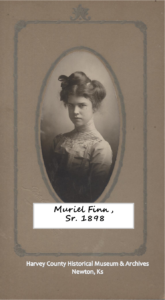

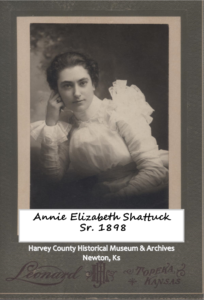

In 1898, the graduating class of Sedgwick High consisted of 8 young ladies. Although their senior photos all look quite serious, they must have had some fun to earn the title of “Giddy 8.”

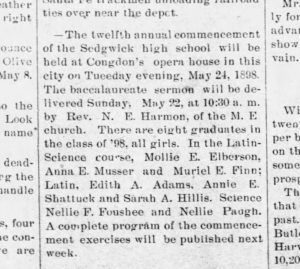

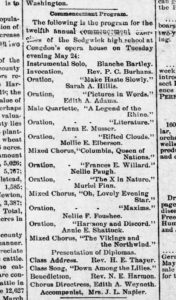

The Sedgwick Pantagraph described the graduation ceremony.

The ‘8 of ’98” Acquitted Themselves Nobly

The “large opera house was crowded to its fullest capacity” for commencement of the Sedgwick High Class of 1898. The class motto was “No brick that fits the wall will be left by that way.” Each graduate presented a oration.

Graduate Sarah A. Hillis delivered “Make Haste Slowly,” and noted that “slow, steady, careful work” were the “stepping stones to success.”

Using “her voice and gestures,” Edith A. Adams “produced a fine oratorical effect” as she presented “Pictures in Words.”

Anna E. Musser spoke on “Literature” in which she “denounced the cheap books of the present day, written merely to sell.”

“Rifted Clouds” was the title of Mollie E. Elberson’s “splendid effort, breathing intense patriotism and thought” throughout the speech.

A “well-worded and nicely delivered eulogy” on the life of Frances E. Willard was delivered by Nellie Paugh.

The oration of Muriel Finn “showed deep research and thought and the phraseology was perfect” as she explored “The X in Nature.”

A vacant chair was placed for Nellie F. Fousbee who could not attend due to illness, which was a “bitter disappointment to her as well as to her many friends.”

The final oration, “Harmony and Discord” by Annie Shattuck was “highly entertaining.”

The diplomas were presented by William Finn, President of the Board of Education. Rev. H. E. Thayer, Wichita gave a “wholesome and earnest class address” followed by a song and benediction to conclude the graduation exercises.

And, the “Giddy 8 of ’98” went out into the world.

Sources:

- Sedgwick Pantagraph, 19 May 1898, 26 May 1898.