by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

“The truth never stands in the way of a good story.” – Jan Hoarold Brunvand

Part 2 for Part 1 Salubrious Soil of Newton’s Boot Hill

Tracing the Story of Newton’s Boot Hill

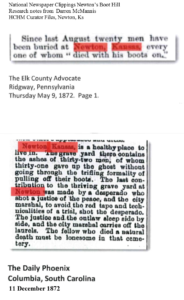

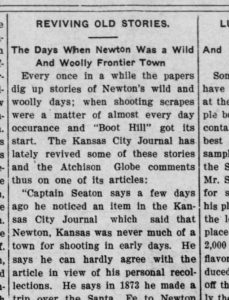

Perhaps the earliest mention of a a Boot Hill Cemetery in Newton was discovered by Newton researcher, Darren McMannus. The two 1872 clippings below are from Pennsylvania and South Carolina, perhaps reflecting the on-going interest by easterners in tales of the ‘wild west.’

Reviving Old Stories

“He can hardly agree”

In 1904, several articles appeared in the Kansas City Journal and The Atchison Globe that noted that Newton “was never much of a town for shooting in early days.” A man identified only as Captain Seaton felt the need to set the record straight. He asserted in an interview with the Evening Kansan Republican that “he can hardly agree . . . in view of his personal recollections.”

Seaton claimed to be a first hand observer although he did not arrive in Newton until 1873. He reported “although not a man had died a natural death in the town, he counted 63 graves in the town cemetery.” He noted that he “scrutinized the markers” which consisted of “boards . . . with names of the deceased printed in rude fashion.” The names included interesting descriptors like “Red Eye Pete,” “Brimstone Bill,” “Wild Ike.” Seaton further recalled an experience he had years ago sitting in a store, he “noticed a skull lying near the road. . . . the proprietor said it was nothing.”

Captain Seaton’s story seems a bit fantastic when compared to other accounts.

Stories abounded in the early part of the 20th century. Many of the old settlers were inspired to tell their stories of the early days of Newton. Like the story told by Captain Seaton in 1904, all referenced the violence in Newton in the summer of 1871.

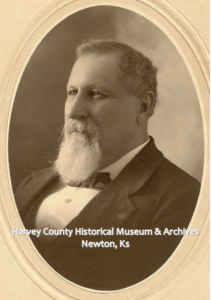

“Frontier Justice” 1908

In 1908, Henry Mayer recorded his memories of early Newton. Mayer arrived in the summer of 1871 to homestead. He served as Newton city marshal 1873 -1894. In 1882, he was credited with “arresting four saloon breakers, single handed at one time.” As a reward for his bravery, Mayer received a “gold Marshal’s badge valued at $100.” During his time as Marshal, he saw “what so many of you did not and never will see” of “frontier justice.” He noted that during this time “Newton had a nation-wide reputation as a bad town.”

“Boot Hill Used for Filling” 1915

In 1915, something of a controversy was stirred up surrounding Newton’s Boot Hill.

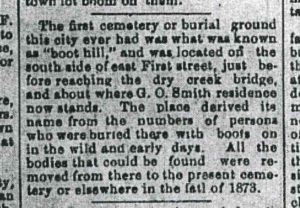

The Newton Weekly Republican reported “Boot Hill Being Used for Filling.” The location was described as “just south of the bridge on East street that spans the ravine which has received the name of Slate Creek, is a knoll of ground that was named many years ago and still bears the name of ‘Boot Hill’.” The knoll in question was being leveled and the dirt taken to a property owned by Dr. J.T. Axtell.

Dr. Axtell had his own story to tell. As a young medical student, he was working with Dr. Hartley in 1879 and he heard a rumor that “Boot Hill was to be placed under cultivation . . . he asked permission to open up some of the graves in the hill, that he might have some skeletons for his study of anatomy.” He removed three skeletons, one of which he still had at the hospital. He noted that “Boot Hill” was “one of the oldest landmarks of Newton.” He recalled that the bodies had been buried in “wooden boxes and buried in everyday suits, no boots were found to substantiate the early day story.”

“There were twelve or thirteen bodies interred there. . . one of the skeletons taken from the know was that of Marten. The clothes identified him.” Jim Martin was one of the men killed in the General Massacre on August 20, 1871.

“Buried on the Knoll” 1907-1915

The reporter interviewed several other men, including Judge C.S. Bowman, on the topic of Newton’s Boot Hill for the 1915 article. Judge C.S. Bowman shared his eye-witness account of the August 1871 General Massacre. Early on Sunday morning August 20, Bowman woke to the sound of gun fire. He estimated “about a hundred shots must have been fired in fifteen minutes.” An inquest was held the next day, however. .” all the men who had been wounded were hidden by their friends and could not be found to give evidence.”

In an earlier document written by Bowman’s wife, Clare Bates Bowman, she noted that “thirteen persons were reported killed and buried on Boot Hill.” In 1871, the Bowman family lived “in a frame built shack between Main street and the cattle trail.”

In a 1912 Bowman was again asked about the early cemetery. In an interview with the Evening Kansan Republican, C. S Bowman described the origin of the name “Boot Hill” located “in the southeast part of town. “

“There was a feud between railroad men and the cow boys which occurred in a dance hall resulting in several deaths and thirteen injured . The men were buried on the knoll since known as Boot Hill from the expression ‘dying with their boots on.'”

“An Every Saturday Night Occurrence” 1921

As part of the celebration of Newton’s 50th birthday in 1921 stories were collected from early settlers.

Henry Brunner operated a restaurant “where the first marshal named Bailey died from being shot . . shooting and killing was an every Saturday night occurrence.” Brunner claimed that seven men were killed and fourteen wounded in one night, with “twenty-four buried in ‘Boot Hill’.”

As a “mere lad,” F. A. Bacon assisted his father in 1871 with his freight business, going between Newton and Emporia. Bacon claimed that “he was here when the first killing took place, and was in the dance hall, and saw the first shot fired at . . . the ‘massacre’.” He recalled seeing “eleven men laid out in a row on the floor and remembers the burial in ‘Boot Hill’.”

John C. Johnston related:

“a fight would be started and they would go to shooting and frequently some cow boy would be shot, killed or wounded. ‘Boot Hill’ cemetery was on east First street, on the south side of the street, and west of the slough. At one time it was said that out of thirty-two interments only two had died a natural death. The others died with their ‘boots on.’ I have always thought that this was an exaggeration, that there were not that many killed.”

“Buried Out on East 1st Street” 1931

C. H. Stewart wrote in 1931:

“they had a ‘Shooting scrape’ in one of the Saloons and some 14 men died that night ‘with their boots on’ and were buried out on east 1st street (just east of the small creek) and it was called ‘Boot Hill’ . . Afterwards dug up and buried in the southwest corner of the present cemetery.”

“South Side of East First Street” 1947

In the History of the First Presbyterian Church of Newton, Ks: 1872-1947, author George Nelson noted that “Newton had its Boot Hill . . . south side of East First Street. . . Thirty-seven murders are recorded. Of the first thirty-two only two were from natural causes.” Unfortunately he does not give any documentation to back up the numbers.

“I Know for Sure” 1961

Mrs. John Reese told this story in 1961:

“Newton’s Boot Hill is out on East 1st Street where you come to that little bridge before you get to the cemetery. It is south of the bridge and halfway between the creek and Ruby Perkin’s house (809 E. 1st) The fence that runs through there is right over boot hill. I know this is true because Grandpa Reese often told us about that and Dr. Axtell went out there and dug up the bones. He studied them in Axtell Hospital . . .This is the reason I know for sure where Boot Hill is or was.”

“Buried in Boot Hill” 1970

In a 1970 document, Irene Schroeder, long time Newton Free Library Librarian, again told the story.

“Mike McCluskie and the others were buried in Boot Hill, which was near First Street and the present Missouri tracks. Later relatives moved McCluskie’s body back to Kansas City or St Louis. Boot Hill was later moved to the northwest corner of Greenwood Cemetery.”

Fact & Fiction

Today, the location of the Boot Hill cemetery described above is private property and not open to the general public.

The stories over the years are consistent with the general location of East 1st and Slate Creek. An early cemetery in this area seems likely. Recently, two researchers attempted to map the area and they found evidence that suggested there had been at least 13 graves in the area. As suggested in the earliest stories, the graves were likely moved to Greenwood in 1872-73.

The majority of stories related to Newton’s Boot Hill cannot be backed up by other sources. They are primarily the memories of people, who were here, but are significantly embellished over time. A review of the Newton Kansan and the Harvey County Coroner Reports for the years 1872-1873, reveal violence in the Newton community, but not to the degree suggested by stories over the years.

Sources

- Bowman, Mrs. C.S. “Organization of Harvey County” typed manuscript, October 7, 1907, HCHM Archives, HCHM, Newton, Ks.

- Mayer, Henry. “Early Days — Newton & Vicinity” typed manuscript, February 29, 1908, HCHM Archives, HCHM, Newton, Ks.

- Reese, Mrs. John. “Boot Hill In Newton.” type written manuscript of the oral interview of Mrs. John Reese by Eldon Smurr, March 24, 1961, HCHM Archives, HCHM, Newton, Ks.

- Schroeder, Irene. Early Days in Newton.” typed manuscript, October 1970, HCHM Archives, HCHM, Newton, Ks.

- Stewart, C.H. “Main Street Sixty Years Ago” typed manuscript, n.d. HCHM Archives, HCHM, Newton, Ks.

- Newton Kansan; 21 January 1915

- Evening Kansan Republican: 1 February 1912; 23 October 1914, 5 March 1921; 1 April 1921; 26 July 1921.

- McMannis, Darren. e-mail correspondence, 18 December 2012.

- Elk County Advocate, Ridgeway, PA, 9 May 1872, p. 1.

- Daily Phoenix, Columbia, South Carolina, 11 December 1872.

- Stucky, Brian. “Newton Boot Hill Exploration” 22 December 2012 research notes, HCHM Archives, HCHM, Newton, Ks.

- Nelson, George W. A History of the First Presbyterian Church of Newton, Ks: 1872-1947. Archives, HCHM.

- http://www.newtonkansas.com/departments-services/parks-and-cemeteries/greenwood-and-restlawn-cemeteries