by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

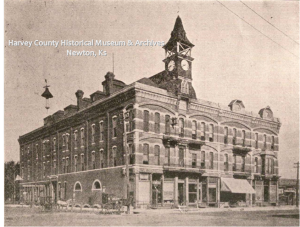

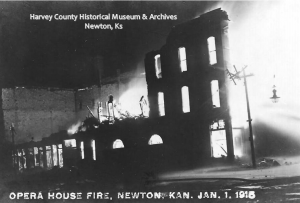

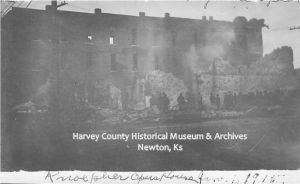

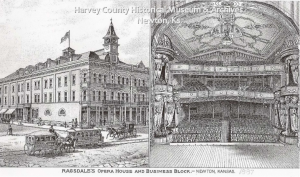

Note: This post concludes our three part series on the Ragsdale/Knoepker Opera House Fire, January 1, 1915.

It is hard to imagine what Thomas H. McManus thought on the morning of January 1, 1915 after viewing the destruction of his business, for the second time in five months. The Weekly Kansan Republican noted that McManus“had no statement to make . . . He is very much discouraged.”

A heavy loser in the fire that consumed the 500 block of Main in August, McManus was temporarily located in the Opera House while he was rebuilding his store at 516 Main.

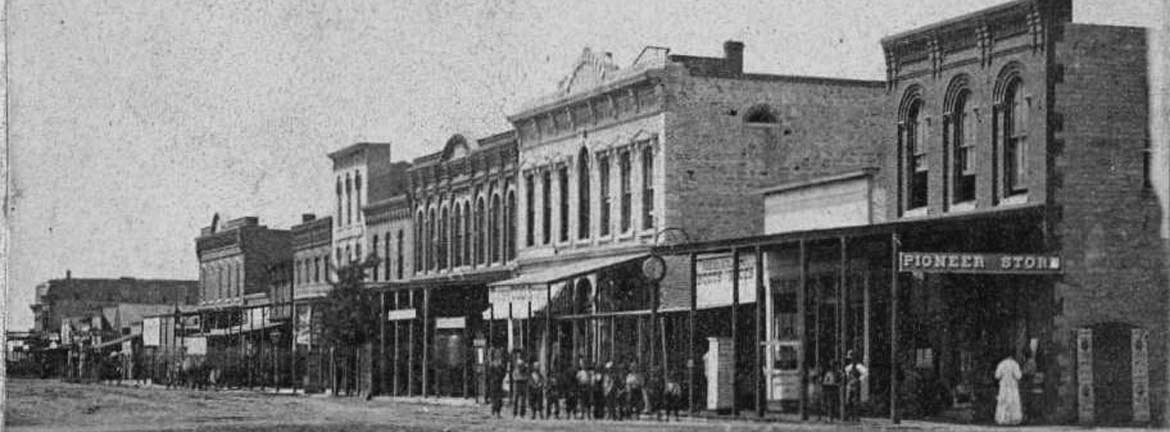

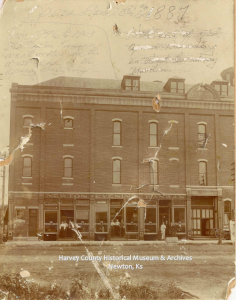

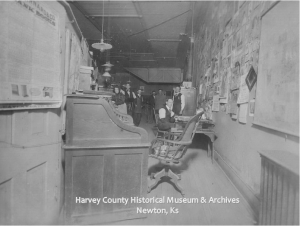

McManus Department Store, 510-512-514, Main, Newton, 1911.

Scene from 4 August 1914, McManus Department Store, 510-512-514, Main, Newton.

According to the newspaper reports after the Opera House fire, he was well stocked with new merchandise.

“The heaviest loser, aside from the owner of the opera block, is T.H. McManus, who has built up the stocks of his department store in this building since the great fire in August, when he was also one of the heaviest losers. . . the rooms occupied were packed full of new goods. the store occupied the entire front of the first floor and a part of the second floor.”

Bystanders had been able to rescue “a few armsful of ready-to-wear garments,” McManus’ desk, and the “safe was dug out of the debris.” Everything else was a loss.

Born in Ireland in the mid-1860s, Thomas H. McManus had immigrated to the United Sates in the 1880s. In February 1895, he purchased purchased the dry goods portion of H.M. Walt’s Newton store. A year later, McManus married a Kansas girl by the name of Bernice. They had at least two daughters, A. Irene, born in 1897, and Bernice, who died at eleven months. For a short time, his brother Bernard, was also part of the business.

Following the opera house fire, the Weekly Kansan Republican had words of encouragement for McManus.

“He has overcome great obstacles . . . and will not himself be overcome by this last disaster. He is, of course, undetermined on future plans in detail, but Newton needs Tom McManus, and will pardon the expressed thought that his greatest asset is his loyal friends in the locality.”

On January 2, McManus announced that the grocery portion of his business would be ready to open at a temporary location on west 6th. In addition, he expected to be in his new building on Main by the middle of January. Noting that he “has employed 113 men . . . and they will be kept at work night and day until the work is finished.”

McManus operated some form of his business in Newton until approximately 1920. At some point after 1920, the McManus family moved to California. Bernnice McManus died in 1928 and Thomas in 1934. There are both buried at the Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, California.

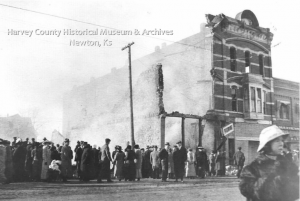

Trousdale Building

Although McManus lost the most, several other businesses also suffered from the fire. The Trousdale Building was the structure to the north of the opera house. A hotel, operated by J.E. Hall, and Marten Motor Co were located in the building. In addition to hotel guests, Hall and his wife lived in the building and lost all of their personal possessions in addition to new furniture for their new restaurant.

Once the structure was “declared safe,” the Martin Motor Co. continued to operate in the Trousdale Building. Until the evening of January 6, when,

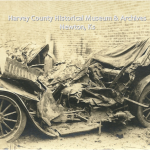

“during the worst of the wind storm they [the walls] were blown over. The bricks fell on the top of Martens garage . . . and the roof on the south side was caved in and the automobiles which were kept in the building were covered with falling brick and wood. . . there is not much chance of any of them being repaired.”

Martin Motor Co. after January 6, 1915

Marten lost two cars, both Buicks, one of which had never been used. Seven other men lost cars they had stored there. Luckily, only one person was in the building at the time, Dora Dahlem worked for Marten Motors, and she was able to get out safely. She reported that “from the noise that was made she thought that an earthquake was taking place.” The damage was estimated to be around $8,000. Following the collapse, “a force of men was set to work . . . tearing down part of the third story in order to prevent another occurrence.”

Total losses for the opera house fire $158,000 and affected six businesses, not including Knoepker’s loss as property owner. Those affected included; T.H. McManus, J.E. Hall, W.J. Trousdale, Mel Reynolds, John Murphy and Martens.

The cause of the fire that consumed the Ragsdale/Knoepker Opera House, took one life, and damaged nearby structures in the early morning hours of January 1, 1915, was never determined.

Sources:

- Evening Kansan Republican, 1 January 1915, 2 January 1915.

- Weekly Kansan Republican, 7 January 1915.

- Newton Journal 8 January 1915.

- Newton City Directories: 1887, 1902, 1905, 1911, 1913, 1917, 1919, 1931.

- U.S. Census, 1900, 1910.

- Early Fire Protection In Newton, Kansas, 1872-1922.

- Newton Kansan 50th Anniversary, 22 August 1922.

- Fent, Mary Jeanine. Ragsdale Opera House — Newton, Kansas, 1885-1915. MA Thesis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1977. HCHM Archives.

- HCHM Photo Archives

- Find A Grave, Thomas H. McManus and Bernice McManus.