A program, “The Latest in Home Entertainment: Enjoying Music in Harvey County,” will be given on Sunday, September 20, 2015 at 2:00 at the Harvey County Historical Museum & Archives. Join us to learn not only more about the way in which “how” we listen to music has changed, but some of the early musical leaders in Harvey County. This post highlights one person who enriched lives with his passion for music.

By Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

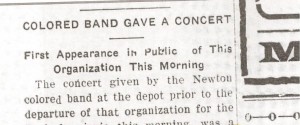

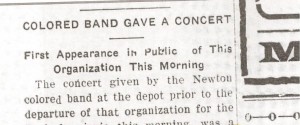

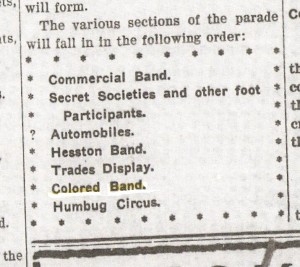

A small announcement in the August 11, 1909 issue of the Evening Kansan-Republican, indicated the start of a new venture in Harvey County.

Evening Kansan-Republican, 11 August 1909, p. 5.

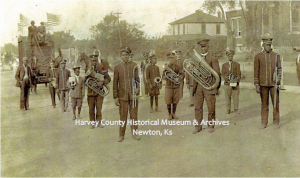

The “Colored Band”** was formed March 3, 1909 with a local man, Lloyd Rickman, serving as director. For some band members this was a brand new undertaking. Several could not even read music. They “applied themselves diligently to practice” and their first concert at the Newton depot in August was a success. After the performance, the band left on the train for Peabody, Ks, where they played for the Peabody picnic. The editor of the newspaper noted that it “was a revelation to most of our citizens who heard it. Many have not known before that this organization existed.”

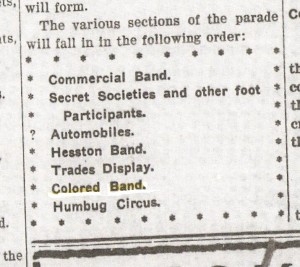

The Band was also one of three bands that marched in the Booster Parade November 2, 1909.

November 1909 Parade Order

Evening Kansan Republican, 2 November 1909, p. 1.

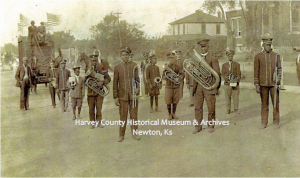

Lining Up for the Parade

“Rickman’s Band” Booster Day Parade, 1909, standing in formation at Main and 8th Street, Newton

The 1922 50th Anniversary ed of the Newton Kansan noted that the band was a “self-supported organization and pays its expenses out of what can be raised through concerts and entertainments.” With the money raised, they purchased instruments and uniforms.

The editor further noted that Rickman’s band was one of the “best colored bands in the state” and the fifteen member band hoped that they “may inspire the people to become better citizens.” The editor concluded that they “work hard to give Newton an admirable colored band.”

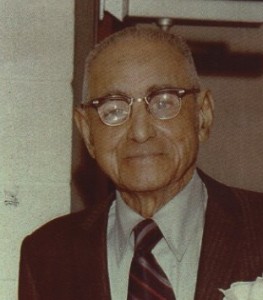

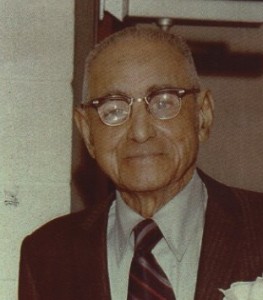

Lloyd W. Rickman

Lloyd Rickman. Courtesy Jullian Wall, Find-A-Grave.

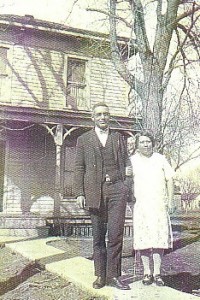

Lloyd Rickman was the driving force behind the band. Born September 19, 1887 to Patrick Rickman and Amanda Burdine Rickman, he married Hazel and they had three children; Lloyd, Kenneth and Ruthabel.

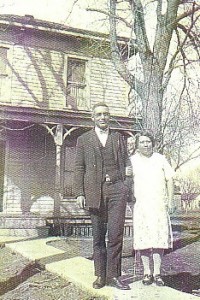

Lloyd W. and Hazel Rickman. Courtesy Jullian Wall, Find-A-Grave .

After the death of Hazel in 1949, Lloyd remarried Josephine Gross Rickman. He was a member of the Hall’s Chapel A.M.E. Church in Newton.

At different times, he worked as a janitor in the city building and auditorium. He also worked as assistant station master for the Santa Fe Railroad. Lloyd Rickman died March 6, 1985 at the age of 97.

Sources

- Evening Kansan-Republican; 13 October 1902, 20 February 1903, 24 February 1903, 11 August 1909, 2 November 1909,24 September 1909, 8 May 1914, 14 September 1917, 2 August 1919, 26 May 1921, 2 July 1921, 25 July 1921, 26 August 1921.

- Newton Kansan: 6 March 1985, 7 March 1985, p. 5.

- “Band Music Has Prominent Place in Newton Community Life,” Newton Kansan 50th Anniversary Edition, 22 August 1922, p. 80.

- U.S. Census 1930, 1940.

- Lloyd Rickman, Hazel Rickman and Josephine Gross Rickman, Find-A- Grave Memorial.

Links to other posts on Harvey County Musicians, and posts related to the Rickman/Anderson family, and Joe Rickman.