by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

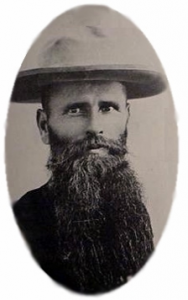

Late in August of 1870, Judge R.W.P Muse left from Topeka, Ks and traveled west and south with several others. He later described some the journey through the vast prairie. On August 28, the group followed the Chisholm Trail

“down on the west side of Sand Creek as far as the mouth of the creek, where we found Dr. T.S. Floyd, with whom we staid all night. . . . After traveling over thirty miles, we had seen no human habitation or sign of civilization, our way being through high prairie grass, often standing above the height of our wagon wheels . . . When we first visited the county, large herds of buffalo were found in the western portion . . . especially where Burrton now stands, and between the two Arkansas Rivers.”

The town of Sedgwick already “did fair business” in 1870 according the Judge Muse in History of Harvey County, 1871-1881. He also noted that “some enterprising and hardy pioneers . . . located in parts of the county as early as 1869.”

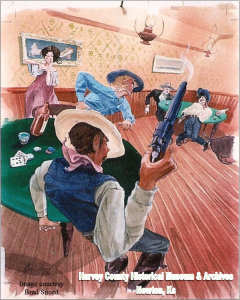

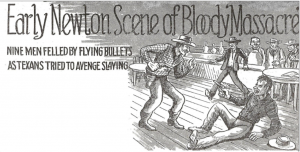

With the arrival of the cattle trade and the railroad in the summer of 1871, the city of Newton grew rapidly and gained a reputation as wild and lawless. Muse, however, saw opportunity in the rough town and decided to stay.

After the shockingly violent summer of 1871 Muse reported that in the fall of 1871,

“the best citizens of the city and county . . . desired law and order to take the place of the disorder and moral confusion. They began to consult for their own protection and the public good and resolved to organize . . . to establish a city and county government.”

Forming a New County

The way to a new county was not without difficulty as ten of the townships were part of Sedgwick County and the others part of Marion and McPherson Counties. Several meetings took place at the law office of C.S. Bowman in Newton to devise a way to create a new county. The final push for a new county came after the Republican County Convention in Wichita. Seven delegates from Newton attended to nominate a county ticket for Sedgwick County. Much their dismay, the Newton delegation was cut to three, and

“after considerable debate and bad temper, all the Newton delegates, headed by the writer, [Muse] withdrew from the convention. . . The strife resulted in the nomination of two tickets, and most of the regular ticket was defeated. This added to the feeling for a new county.”

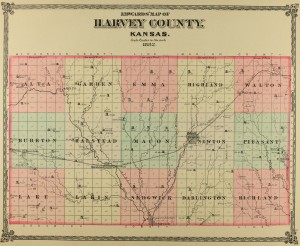

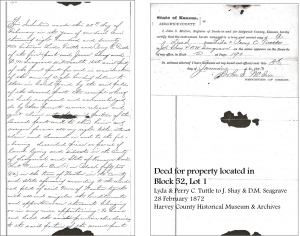

A meeting to establish a new county was held on December 13, 1871 in the office of Muse & Spivy, in Newton. The group was able to get the support of Capt. David Payne, the representative in the Kansas legislature. Several worked on completing the necessary paperwork including C.S. Bowman and Dr. Gaston Boyd. The new county would consist of sixteen townships, ten from Sedgwick, three from McPherson, and three from Marion.

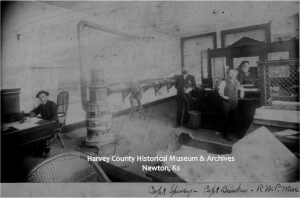

Office of Judge RWP Muse and Capt. Spivey, Newton 1872. Spivey is sitting at the desk, Judge Muse is behind the counter and the man in front of the counter is identified as Capt. Bunker. Fourth man is undientified.

Harvey County organized by Act of Kansas legislature on 29 February 1872. The new county was named in honor of James M. Harvey, who was the governor of Kansas at the time.

A County Seat

Newton was designated as the county seat, but not without controversy. A vote was held on May 20, 1872 for county officers and county seat. and there were some irregularities.

Judge Muse reported the following:

“The poll books of Sedgwick township showing up on their face an excessive and fraudulent vote, equal to more than double the amount of inhabitants in said township at the taking of the census about the 1st of April 1872, and the poll books of Newton township showing a large and excessive vote. . . The census of Sedgwick township taken and filed just before the election, showed that there were not to exceed one hundred and twenty-five legal voters residing in the township, yet the poll books showed that at the election over seven hundred votes had been cast. . . .It was reported that the names upon the Sedgwick poll books were copied from the Cincinnati Directory, and a colored bootblack who was plying his vocation there on election day, is reported to have . . . voted fourteen times.”

Muse concluded; “At any rate, beyond a little strife in court, no harm resulted and Newton was declared the county seat of Harvey County.”

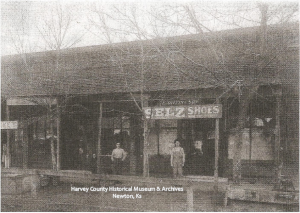

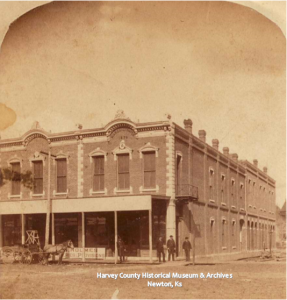

The Johnson Building located at the corner of Main and Broadway in Newton was designated as the location of the county offices. The offices soon moved to a 526 Main. Two years later, in 1875, the county offices were moved to the second floor of the Hamill Building at 513 Main.

In 1880, the county offices were located in the Masonic Building at 700 N. Main.

In his concluding remarks on the history of the county, Muse noted that Harvey County was

“filled with enterprising people, who take great pride in the thrift and prosperity of their respective towns, and whose public spirit ensures the steady growth of these cities, . . . and renders their success certain.”

*****All quotes are from “History of Harvey County: 1871-1881 by Judge RWP Muse, 1882.

Sources

- “Death of Judge Muse” Newton Kansan 26 November 1896, p.1.

- Muse, Judge R.W.P., History of Harvey County: 1871-1881. Newton, Ks: Harvey County Historical Museum & Archives, 2013. Originally published in Edward’s Harvey County Atlas, 1882.

- Bowman, Mrs. C.S. “Organization of Harvey County” typewritten document dated 7 October 1907, HCHM Archives, Newton, Ks.

- Mayer, Henry. “Early Days — Newton and Vicinity” typewritten document dated 29 February 1908, HCHM Archives, Newton, Ks.

- HCHM Photo Archives, Newton, Ks