by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

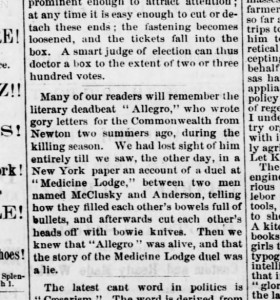

“He sat at the faro-table with the whole of his expressive face in full view, . . . I recalled the hour when three years before, in a Newton dance-house, I was a looker-on and saw the silver-mounted pistol now peeping out at his breast send death into the bosoms of three human beings. This was Anderson, the Texas desperado, the horse-thief . . . the red-handed murderer. I had written of the dance-house tragedy. I had held him up to public execration . . . had even advised the formation of a vigilance committee to inflict on him summary vengeance.” (J.H.E., “Meeting of the Desperadoes” New York World, 22 July 1873 reprinted in full in Ellison, “The West’s Bloodiest Duel-Never Happened!” p. 3)

Part 2 of two posts For: Part 1.

What Did Happen to Hugh Anderson, Texas Cowboy and Desperado?

One basic fact proves that the duel story written by Allegro/Harington was fiction. Hugh Anderson lived another 40 years. He married twice, had three children and was a successful stock man. U.S. Census records show the movements of the larger Anderson family including Hugh in Texas and New Mexico. He clearly did not die in a duel in the fictional town of Medicine Lodge, I.T. in July 1873.

Hugh Anderson was born in DeWitt County, TX on 25 November 1851. He was the third of 10 children born to Walter Pool “Wat” and Louisiana “Lou” Bailey Anderson. In 1868, Hugh and his older brother, Richmond were involved in a “blood feud” between neighboring families named Taylor and Sutton in Texas. Richmond reportedly killing a man during this time. During the summer of 1871, Wat, sent a herd of longhorns up the trail to the new shipping point at Newton, Ks. His son, nineteen-year-old Hugh was on the drive, perhaps to remove him from the feuding families.

While holding the herd near Newton, Hugh met the soon-to-be famous killer, John Wesley Hardin, who was pursuing a Mexican outlaw named Bideno. Hugh rode with Hardin and was present when Hardin killed Bideno. Hugh then returned to his duties watching his father’s herd near Newton. Perhaps when he arrived in Newton, he learned of the death of Bill Bailey, who had been shot by Mike McCluskey earlier in the week. The death of Bailey angered Hugh and he threatened McCluskey. Bailey may have been a relative of Hugh on his mother’s side adding to the motive for vengeance.

After the shootout in Tuttle’s saloon, an injured Hugh was secreted out of Newton by his father with the help of several Newton businessmen. He returned to Texas. Maybe the experience taught him something as he seemed to ‘settle down’ and live in a more law-abiding manner.

On July 11, 1872 in Bell County, Tx, Anderson, age 20, married 22-year-old Amanda Tomlinson. In May 1873, their son, Oscar was born. The supposed duel took place on July 4, 1873. The article in the New York World appeared July 22, 1873.

Three years later, Hugh, still very much alive, but a widower, moved with his young son, and several other family members to McCullock, Tx. The 1880 Federal Census listed Hugh, 28, and son, Oscar, 7, living with his parents and working as a “stock raiser” in McCullock County, Tx.

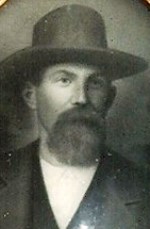

Hugh Anderson. Courtesy Simon Duran, Find A Grave #13728884 .

In 1884, at age 32, Hugh married a second time, Mag Cooke. They moved to Chaves County, New Mexico Territory and Hugh continued to work as a stock man. They have at least two girls. The U.S. Census for 1900 listed Hugh as a widower. In 1910, Hugh is listed as a stock man and living with his married son, Oscar, and three grandsons.

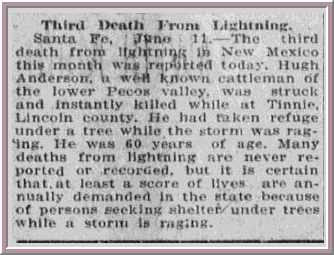

Hugh Anderson died 9 June 1914 at the age of 62 while herding cattle in Lincoln County, New Mexico. He was struck by lightening “and instantly killed . . . He had taken refuge under a tree while the storm was raging.”

Hugh Anderson. , Courtesy A. Firefly, Find A Grave #13728884 .

Hugh Anderson. , Courtesy Delma Ingram, Find A Grave #13728884 .

Years later, Hugh’s younger brother, Wyatt, described his father’s cattle drive during the summer of 1871 to Newton. He confirmed that Hugh was on that drive and had killed a man in Newton during the big fight. He also detailed the actions of the oldest Anderson brother, Richmond, who was involved in two killings, one in Texas, the other in Wichita, Ks during the early 1870s. He made no mention of a supposed duel at Medicine Lodge or anywhere else.

One wonders if Hugh ever read Allegro’s account of his death and what he might have thought of the “West’s Bloodiest Duel.”

Sources

- United States Census 1880, 1900, 1910.

- Muse, Judge R.W.P., History of Harvey County: 1871-1881. Newton, Ks: Harvey County Historical Museum & Archives, 2013. Originally published in Edward’s Harvey County Atlas, 1882.

- Ellison, Douglas. “The West’s Bloodiest Duel-Never Happened!” Western Edge Books, 3 December 2014 at westernedgebooks.com.

- Hugh Anderson. , Find A Grave #13728884 .

For the full article by Douglas Ellison see The West’s Bloodiest Duel – Never Happened.

![Gunfight_note[1]](https://hchm.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Gunfight_note1-265x300.gif)