by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Archivist/Curator

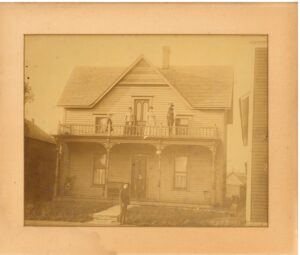

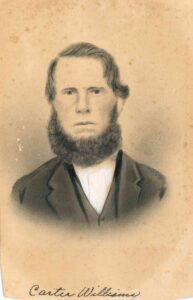

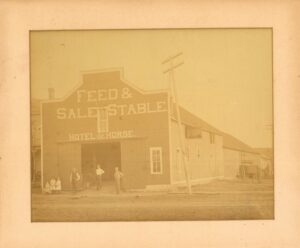

Recently the museum received three photos with limited information. The donor had been told by older relatives that they were photos from the time their family lived in Newton, Ks. The donor’s grandfather was Joseph Murphy, but had been born in Newton with the name Job Combs March 26, 1885. The photos are of a house, a Feed & Sale Stable and a man identified as Carter Williams. The house photo had the Mrs. B.F. Denton photographer stamp on the back along with the color scheme of the house.

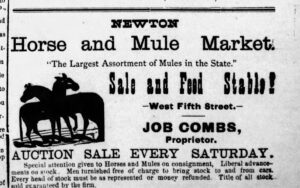

Research started to discover the location of the Feed & Sale Stable business, but the mystery of the Combs became the story long after the location of the stable was known. The Feed & Sale Stable was located at the corner of 5th & Poplar, Newton in 1885. The business was owned by Job Combs, but who was he?

The Feed & Sale Stable was located at the corner of 5th & Poplar, Newton in 1885. The business was owned by Job Combs, but who was he?

The Mystery

The biggest question surrounded the identity of Job Combs and why did he change his name to Joseph Murphy? The second was the identity of Carter Williams and how did he connect. The first thing discovered was there were two Job Combs – a father and son.

Job Combs Family in Newton

In 1871, 28 year old Job Combs arrived in what would become Harvey County with his 16 year old wife and several children, the oldest William was eleven. Job was born in Indianna in 1843 and served in 2nd Indianna cavalry. An oral story in the family says that he was a spy, but when he was captured, he was able to escape due to his slender wrists. He lists his occupation as “jockey” in the 1880 Census. His wife, Mollie, or MJ, was born in Arkansas in 1855 and listed her occupation as “Keeping house.”

Ten years later Job Combs announced that he was an independent candidate for the office of sheriff. He noted that he was not a politician and had never run for office. He served in the military as a member and promised; “if elected he will be a terror to horse thieves and other law-breakers throughout the ‘Great Southwest’.” (Weekly Republican 7 September 1881) He did not win election.

Throughout the early 1880s, Job Combs worked for various stables in Newton including the Ensign Stable.

The next mention in the newspapers is on September 27, 1883, when R.O. Tyler was put on trial for selling liquor to Job Combs. The complaint was brought by his wife, Mollie Combs who had instructed Tyler not to sell to her husband. Over forty witnesses were subpoenaed in the case.

Life must have stabilized for the Combs family for a few years. In 1885, Combs bought two lots at the corner of 5th & Poplar and erected a stable 32′ x 110′. (Newton Democrat 24 April 1885).

He built a house next to the stable “with six rooms, a good well and cistern, cellar and every convenience.” (Newton Democrat 12 Jun 1885)

Baby Combs

Earlier in March the Combs family added one last son to the family. On March 27 1885 the Newton Democrat offered congratulations to the Combs family on the birth of a son named Job Combs.

“Mrs. Job Combs . . . presented her leige lord with an heir – a son who kicks the beam at 12 pounds avoirdupois . . . the mother and child are doing nicely and hopes are entertained that the father will if an antidote can be found for his excessive hilarity. We congratulate, you Job, and wish you many, many -er, er, well, many happy days, even years , with the youngster.” (Newton Democrat 27 March 1885)

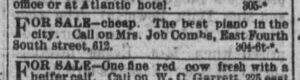

“The Best Piano in the City”

Two years later, Combs sold home on 5th and bought a farm three miles west of the Fair ground. His land and other assets are sold at a sheriff’s auctions in 1892 and 1889.

Job Combs and Mollie Williams Combs divorced May 18, 1888, and Mrs. Combs began selling furniture. One item in particular was a point of contention, “the best piano in the city.” Mrs. Job Combs advertised it for sale in 1888. It is possible that her ex-husband Job did not agree to the sale of the piano. In May 1891, this piano became the focal point when Job Combs was arrested for disturbing the peace in an altercation with D.S. Welsh. Welsh had possession of the piano.

Combs spent time in the City jail and was fined $5 and costs as a result. No further word on what happened with the piano. Job Combs does not appear in the Harvey County papers after 1892.

Who Was Mrs. Mollie Combs?

Born in Arkansas in 1855, she married Job Combs young, possibly at the age of 14. She came with him to Harvey County in 1871. After the divorce from Job Combs, Mrs. Combs’ name begins to appear in the Police Court sections of the newspapers.

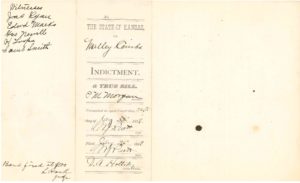

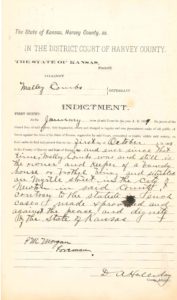

In 1890, Mollie Combs got in trouble with the law as “a proprietress of a bawdy house.” Her establishment was located on E 6th and was known as the Atlantic House. In June 1890, Dr. Earnest Schurchart was arrested for violating a prohibitory liquor law. Schurchart, described as a “German of rather disreputable character whom it is said has only been out of the penitentiary a short time,” was living at the Atlantic house. One witness against Schurchart was Mrs. Combs son. Mrs. Combs was “fined $50 and cost for keeping a house of ill fame.”

The 1900 Census shows that Mollie has moved to Minneapolis, Minnnesota and is married to Patrick Murphy. Included in the census is a 16 year boy named Joseph Murphy born 26 March 1885 in Newton, Kansas. Patrick Murphy is listed as his father.

Who Was Patrick Murphy?

In a document with the U.S. Social Security Numerical Identification Files, Name and Form, 1943 for Joseph Murphy, Patrick Murphy is listed as the father and Mollie Williams is listed as the mother. Joseph’s birthdate was 26 March 1885 in Newton, Ks. Was Patrick Murphy Job Combs’ actual father?

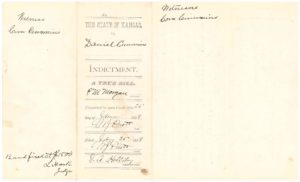

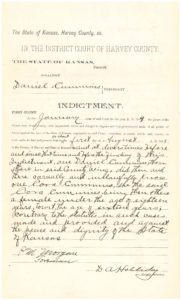

Patrick Murphy was a difficult man. He lived in Burrton, Kansas. He was a known gambler who regularly beat his wife. For example, on December 23, 1890, the Newton Daily Republican reported; “Sheriff Pollard has gone to Burrton for Patrick Murphy who is accused of assaulting his wife and children.”

Samantha Murphy received a degree of divorce from Patrick Murphy on the ground of extreme cruelty February 27, 1891.

Job Combs/Joseph Murphy

Joseph Murphy made a life in Hennepin, Minnesota. He married Ollie L. from Norway sometime before 1910. They had one child, Amy Virginia Murphy.

On an application to change his name dated February 1943, Job Combs officially changed his name to Joseph Murphy and listed his parents as Patrick Murphy and Mollie Williams. Just a few years later on documents related to his death on 2 April 1948, Job Combs is listed as his father, Mollie Williams his mother and his spouse was Ollie L. Murphy.

Job Combs/Joseph Murphy was 63 years old when he died at St. Louis Park, Hennepin, Minnesota.

Loose Ends

Mollie Williams Combs Murphy died in January 1925 at the age of 80 in Minneapolis, MN. She was survived by her sons Joseph Murphy, Harry C. Combs and William Combs, daughters Nellie Combs Halliday and Amy Combs Drain.

At this date, nothing more has been found on Job Combs (the elder) or Patrick Murphy.

Who Was Carter Williams?

The last mystery includes the photograph identified as Carter Williams, “grandfather of Job Combs who changed his name to Joseph Murphy.” Evidence suggests that the photo is of Mollie Combs Murphy’s’ father. No evidence could be found that he ever lived in Harvey County.

Sources

- Divorce Index, 1872-1940, Archives Indexes, Harvey County Historical Museum & Archives, 203 N Main, Newton, Ks.

- Burrton Graphic: 27 December 1890,3 July 1891, 30 September 1892,

- Newton Daily Republican: 18 June 1890 27 June 1890 23 December 1890.

- Newton Democrat: 12 September 1884, 17 September 1886.

- Newton Journal: 20 June 1890.

- Newton Kansan: 20 September 1883, 1 September 1887.

- Weekly Republican: 25 September 1885, 26 December 1890, 27 September 1891.

- Kansas County Marriages, 1855-1911, Charles C Flowers and Amy Combs, 1 June 1886.

- Kansas County Marriage Records, 1855-1911, Ira Combs and Mary Elisabeth Simpson, 12 May 1890.

- Kansas County Marriage Records, 1855-1911, Wm M Combs to Luella Callager, 11 August 1889.

- Kansas County Marriages, 1855-1911, Patrick Murphy and Samanta Gibson.

- Kansas Naturalization Records, Partrick Murphy 10 October 1887.

- Minnesota Deaths, 1887-2001, Entry for Joseph Murphy and Job Combs, 2 April 1948.

- U.S. Social Security Numerical Identification files, 1936-2007, Joseph Murphy.

- U.S. World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1942, Entry for Joseph Murphy and Ollie L Murphy.

- U.S. Census: 1880, 1885, 1900.