by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

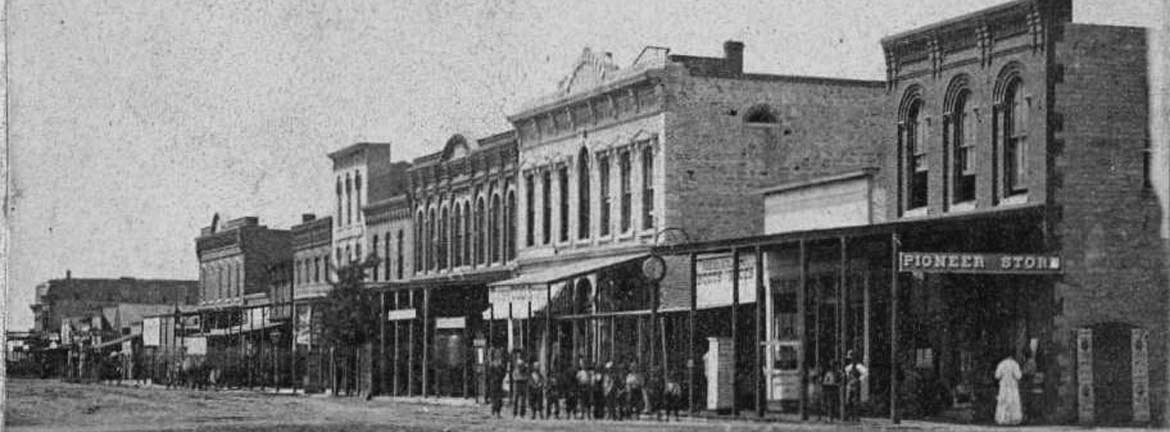

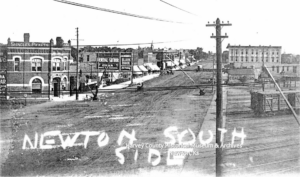

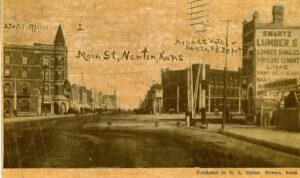

Trains. A fact of life in Newton, Kansas since 1871. Anyone who has spent any time in Newton has likely had to wait on a train and wondered can something else be done? An overpass? or perhaps, a subway? Throughout late 1899 and early 1900, there seemed to be serious consideration into the idea of putting a subway or viaduct at one or several of the railroad crossings in Newton.

In September 1899, Newton City council passed Ordinance No. 434, “granting Santa Fe permission to lay a subway across Main street for steam pipes connecting the Arcade and Clark buildings.” Even though this did nothing to fix the traffic problems, maybe the idea of a vehicle subway was planted.

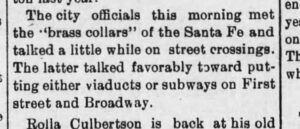

“The city officials this morning met with the ‘brass collars’ of the Santa Fe and talked a little while on street crossings. The latter talked favorably toward putting either viaducts or subways on First street and Broadway.” ( Evening Kansan Republican 8 August 1899)

“Had It Not Been for Her Grit”

In addition to the inconvenience for people trying to get across town, the intersections were dangerous, especially for horse drawn buggies.

One such incident was reported in May 1899. Mrs. Sam Bourne was driving south on Main when she had a collision at the Santa Fe crossing. The paper noted, “had it not been for her grit, it might have ended seriously.” Two engines were at the crossing, and Ed Slaymaker’s horse became spooked. The horse ran against Mrs. Bourne’s horse, “and in a jiffy her rig was overturned.” Mrs. Bourne was praised for preventing a runaway by holding onto the reins even though she was thrown from the buggy. Luckily she was not hurt. Horses and train engines were not a good combination. (Evening Kansan Republican 30 May 1899)

“The Question of the Santa Fe Crossings”

Throughout the months of February and March 1900, the question of a subway at one or more of the crossings in Newton was considered by the City Council, Commercial Club and the Santa Fe Railroad.

The Commercial Club held a special meeting only for members January 31, 1900 “for the purpose of discussing the question of the Santa Fe crossings.” All members were required to attend and to be ready to “speak to the question intelligently.”

The Commercial Club further noted that

“there is need of immediate action in this line it is no long a question for discussion. No one realize this more than the officials of the Santa Fe . . . they have signified their intention of doing something as soon as the will of the people is ascertained. “

Following the meeting the members were instructed to talk to community members “in an effort to ascertain the sentiment of the people.”

The general consensus, even before the January 31 meeting was that “the disposal of the First street and Broadway or Seventh street crossings seems to be an easy matter, but Main street promises to be a more difficult matter.”

“The Greatest Objections”

In a report from the meeting in the February 1 issue of the Evening Kansan Republican, the editor shared some of the objections to the subway.

The strongest objections were regarding the Main street crossing. People were against anything that would ultimately result in the closing of Main Street. One stated reason was “it will spoil the appearance of the Main street of the city.” In addition to changing the look of Newton’s Main Street, it “would divide the town almost as effectually as a stone wall.” The City also was unwilling to assume any damages that might result to property adjacent to the proposed subway. Finally, the property owners around the area of the proposed subway had “the greatest objections.” They observed that the value of their property will suffer.

The editor of the Evening Kansan Republican replied to the business owners with a quip of his own. “On the other hand, the safety of life and limb museum be taken into consideration.”

There was a strong feeling that Santa Fe “should stay by the original contract and always keep open Main, First and Walnut street and Broadway.” Some suggested a subway or viaduct constructed near Main either from 4th or 5th streets.

The editor concluded his report “it is up to the people now to say what they want.”

At the regular meeting of the City Council on 1 February 1900, a committee of representatives from the Commercial Club including J.C. Nicholson, D.W. Wilcox, S. Lehman, reported to the city council. They had been meeting with the Santa Fe regarding a subway. The City appointed Williams, Spooner, and Bennett from the City to meet with these groups and report back “as soon as possible.”

Thoughts From the Street

Meanwhile, everyone had an idea or opinion of how to solve the problem.

An Elevator

One big concern was that Main street remain open. Some people had creative ideas to accomplish this.

J.R. Pruit offered the following as a solution to keep Main street open.

“An elevator on both sides of the track. Vehicles can be lowered to the subway, drive through, ‘ring’ the other elevator down, go up and drive off. He has not drafted the plans and specifications for the scheme yet.” (Evening Kansan Republican, 3 February 1900)

“You May Quote Me”

Others thought a subway was entirely unnecessary.

“You may quote me as being against a subway or viaduct on Main street. We don’t need one there. Did you ever hear of anyone being hurt there? Of course you didn’t. What accidents have happened in the vicinity were due entirely to the carelessness of the victims, and they didn’t happen on the crossing but in the yards. What we do need, as a time saver is a viaduct across from Fifth street.” N. A. Mathis (Evening Kansan Republican, 26 March 1900)

“What do You Think of a Subway?”

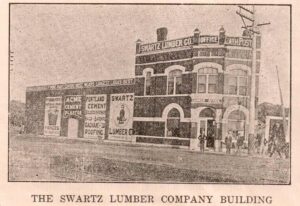

The editor of Evening Kansan Republican posed this question to several men one cold, windy February evening just as a “long freight train was pulling over the crossing” at Main. The group of men, standing in the sleet and rain, had businesses on the north side of the track. They were returning to their homes on the south side of the track for the evening. One merchant replied, “Oh, gives us anything in that line you can think of. We are not at all particular what it is.” The editor could not help but notice that none of the businessmen had a business in the block just north of the track.

Santa Fe’s Proposal

By March 1900, they had a proposal ironed out. Mayor Young and Commercial Club President Hoisington met with Supt Dolan, J.H. Banker and Engineer Earl from the Santa Fe, “in regard to the proposed subway the company has offered to build.”

The proposal from the Santa Fe was as follows:

“The company will build a subway under its tracks and across vacant lots, commencing at East Seventh and ending on Broadway west of Kansas Avenue and will open a street from Broadway to Sixth.”

The estimated cost was $16,000. In return, the Santa Fe asked the City to close the Broadway and Walnut street crossings. “Main street and West First street was left for further discussion.” (Evening Kansan Republican, 17 March 1900)

The city council meeting on 3 May 1900 was “a long session and transacted much business. All members with Mayor Young, were present.” The first order of business was a motion from the “railroad crossing committee” consisting of members of the city council and the commercial club.

A motion made by Mr. Spooner and carried unanimously,

“it is the sense of this committee that the proposition for a subway at Seventh street, submitted by the A.T. & S. F. Ry., does not furnish a practical and satisfactory solution to the question involved and can not be recommended to the people.”

“Second, . . . that a crossing should be constructed at right angles to the railroad at the point just west of the present freight depot, that the north and west approach be on Sixth street and the south and east approach be over the fractional block 58 to Pine and Fifth streets.”

The idea of a subway seemed to be finished.

“Nestled Away in Some Remote Corner”

Not everyone was satisfied with the outcome. The editor of the Evening Kansan Republican printed a conversation he had with several men who were not ready to let the matter rest. In the 22 December 1900 issue, he published a column entitled “Saturday Night Talks.”

He described a conversation with several men. They noted that there had been several recent accidents at the Main street crossing, including one fatality, “yet we hear nothing about the subway.”

One complained, “recently we have heard nothing about the matter. The whole subject seems to have wrapped itself in a slumber robe and has been nestled away in some remote corner of the council chamber.”

Another individual responded, “Well, the railroad was here first, I guess, and the town built on both sides of it. It wasn’t the fault of the railroad.”

A friend challenged him on this. “Hold on now . . the city of Newton is a child of the railroad. The railroad company laid it out on both sides of the track way back in 1871. It sold town lots and encouraged building other south as well as on the north side . . . If the city waits until the railroad voluntarily remedies the matter, it will wait a long time.”

After the editor faithfully reported the discussion he noted “that it is not the citizens of Newton alone who are interested in the subject. It interests every citizen of the county who, in the transaction of his business, is compelled to cross the tracks on Main.”

Continuing Discussion

Over the next few years, there would be subtle and not so subtle mentions in the Evening Kansan Republican.

“The Question of the Santa Fe Crossings”- 1901

In the January 30 issue of the Evening Newton Kansan, the editor again asked the question” “Has the proposition to build a subway or a viaduct at the Santa Fe crossing been laid on the table?”

Subway Agitation Revived? 1902 Headline

“Subways are Needed” – 1904

The matter was again brought up in May 1904. Another committee was formed. It was noted that there remained strong feelings “among the councilmen . . . that Main street must be kept entirely open, no matter what subway plans are adopted. The council recognizes the most imperative need of a subway crossing at Seventh street and West First.”

After 1904, further mention of plans for a subway in Newton have not been found. Safety, however, continued to be a concern.

“The fool that rocks the boat has a close rival in the fellow who tries to cross ahead of a train.”

The editor of the Evening Kansan Republican observed in September 1910 that

“hardly a day passes but what there are narrow escapes on Main street where people who are foolhardy enough to cross just ahead of the train.”

He scolded his readers noting, “The gates are lowered . . . for the protection of the public . . . but to watch the people who cross the tracks, one would think the people did not want any protection but wanted . . .more of an element of danger.”

He urged the readers to “exercise a little more judgement at the crossing.”

The railroad crossings at Main, Broadway and 1st street continue to be a challenge to Newton drivers 122 years later.

Sources:

- Evening Kansan Republican: 8 August 1899, 8 September 1899, 26 January 1900, 30 January 1900, 31 January 1900, 1 February 1900, 2 February 1900, 3 February 1900, 8 February 1900, 17 March 1900, 26 March 1900, 4 May 1900, 22 December 1900, 30 January 1901, 15 May 1902, 24 May 1904, 2 September 1910,