by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Archivist/Curator

Thanks to Jim Brower for sharing this advertisement card to start us on our search.

Many of us are happy to be able to get out into our gardens again after a long winter. We have our favorite nursery or Garden Store to go to for supplies, seeds and plants. Just like now, 1880s Harvey County had several nurseries, including the Harvey County Nursery, Halstead, Ks owned by Joseph Cook.

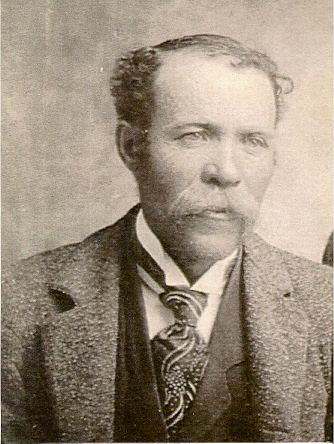

Joseph Cook was born in Indiana in approximately 1825, he first appears in the Halstead paper in 1881 as an agent for Dr Ryder’s American Fruit Dryer or Pneumatic Evaporator which was advertised as being “equal to canned goods and is saving the cost of cans, jars etc.” He had one on his farm 3 1/2 miles north of Halstead in operation and “he would be pleased to have his brother farmers come and see work and test the fruit.” (Halstead Independent 5 August 1881) In the 1875, he is listed with his wife Mary and three children John Jay, 18, Emma, 14, Melona 3.

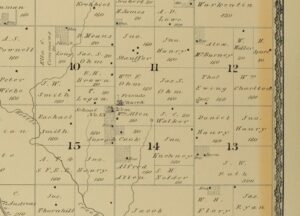

By 1882, Joseph Cook had an establish tree stand that included fruit trees. He had 160 acres in section 15 and 80 acres in section 14, Halstead Township, Harvey County, Kansas. In addition to the orchid, the plat indicates a residence and two other buildings. A one room school was also located at the corner of section 15. The map also shows the location of the Friends Church, of which he was a member, and the cemetery.

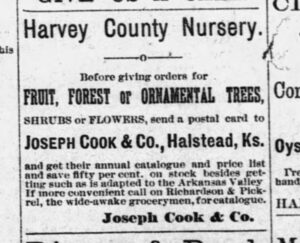

Harvey County Nursery

In 1885 the Halstead Independent reported that they would be publishing a “treatise on “Growing an Orchard in the Arkansas Valley'” written by Joseph Cook. At that time the Harvey County Nursery were known for their Apple, Pear, Soft Maple, Hardy Catalpa and Russian Mulberry trees, grape vines and evergreens. In the spring of 1885 their goal was to be the “best evergreen nursery west of Topeka.” To meet that goal they had several thousand evergreens for sale. He also wrote advice columns on growing various plants occasionally for the Halstead Independent.

In the fall of 1885, Cook made the decision to move his business closer to Halstead. Business had increased over the summer and it was inconvenient to be a distance from town. They purchased 60 acres of land from Frank J. Brown.

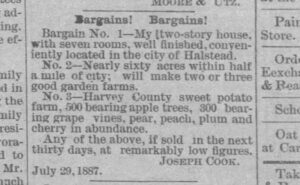

By the end of 1886, Cook was advertising to sell the nursery. The editor of the Halstead Independent noted, “while we should regret to see these parties retire from the business . . .it is a rare opportunity for some enterprising man . . . to invest in a profitable and pleasant business.”

August 5 1887 in an advertisement for his farm Cook describes a two story house with seven bedrooms, close to 60 acres within a half mile of Halstead, and finally a sweet potato farm, 500 bearing apple trees, 300 bearing grape vines, pear, peach, plum and cherry in abundance.

From Halstead to Rialto, CA

October 14, 1887 make their homes not only in Southern California, but at the beautifully located projected town of Rialto.” Among those than made the mover M.V. Sweesy, former editor of the Independent, J.W. Tibbott, dry goods and stock raiser, Joseph Cook, farmer and “influential member of the Quaker church,” J.W. Sweesy,, farmer. Wm Tibbot, merchant, Frank Brown, farmer, and Leroy and Mr. McDonald, “two estimable young men.”

The Halstead Independent kept up with Cook for a few years in the November 11, 1887 issue a letter from Cook in California was published. Then in May 1888, there was a report that Joseph Cook and the Tibbot brothers “were on the outs.” Cook himself felt compelled to answer writing; “there is not the least bit of foundation for the slang about me and Tibbots . . . I look upon it simply as malicious lying, nothing less.”

One final mention of Joseph Cook in the Halstead Independent came from the Rialto Orange-Grower in California. “Mr. Cook and family have returned for Jennings, La to Rialto . . . Mr. Cook has not yet determined definitely as to his future movements. He may remain with us or may move to some point farther north on the coast. We trust he will find it to his advantage to remain and make his home in Rialto.”

“Two Prohibitionists Discussing Prohibition”

In addition to growing his business, Joseph Cook had a passion for temperance. From 1883 to 1886, Cook’s name appears frequently advocating for temperance and supporting strict enforcement of Kansas’ Constitutional law. He wrote several lengthy articles published in the Newton Kansan and Halstead Independent.

At the Prohibition Convention in September 1886, Cook was elected president and gave “a short but appropriate speech.”

On October 29, 1886, Cook engaged in a discussion at White’s school house with Hon. T.J. Matlock. The Halstead Independent editor noted that “it was, however, a rather queer discussion. Two prohibitionists discussing prohibition.” While both gentlemen acquitted themselves well, “it was conceded, we believe, that Matlock got the better of the argument and really out Ceasared Ceasar himself.”

Cook spoke again November 5 1886 at a political meeting featuring the Hon T.J. Matlock, two other men spoke Charles Bucher, of Newton on November 5, 1886 and gave lectures at the Y.M.C.A. in Newton.

It is not known if he continued to be active in the Prohibition movement once in California.

Sources

- Kansas State Census, 1875.

- United States Census, 1880.

- Halstead Independent: 5 June 1885, 30 October 1885, 20 November 1885,10 Sept 1886, 29 October 1886, 3 December 1886, 11 January 1889.

I really appreciate sharing this great post. I like this blog and have bookmarked it. Thumbs up

Great,great, granddaughter of Amos. I just discovered Amos Frazier’s obituary. It stated that he was a man of kindly, jovial disposition a good neighbor and friend. In his later years he served as night marshal of Sedgwick. I enjoyed learning another side of his character.