This is an updated article based on a previously published post on Friday, February 8, 2013 at Voices of Harvey County: Stone Mason – Joe Rickman (harveycountyvoices.blogspot.com)

by Kristine Schmucker, Curator

This is the second in our series featuring the Rickman/Anderson/Clark/McWorter families who settled in Harvey County in 1871. For the first installment which features Mary Rickman Anderson Grant see: An Ordinary, Amazing Woman: Mary Rickman Anderson Grant – Harvey County Historical Society (hchm.org)

Eldest Son

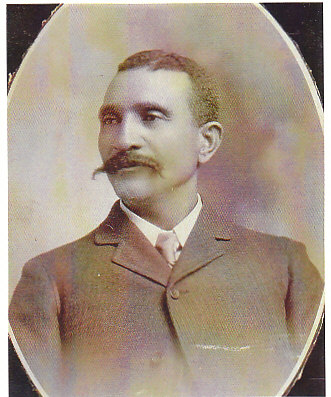

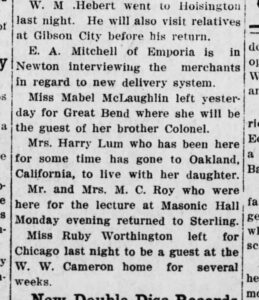

Joseph C. Rickman was Mary Rickman Anderson Grant’s oldest son. Joseph was born November 2, 1850 in White County, Tennessee. His mother, Mary, was about 15 years old when he was born. It is uncertain who his father was; according to family genealogies David Anderson, Mary’s first husband, was not his father and Joseph always used his mother’s maiden name, Rickman. On his death certificate, however, David Anderson is listed as his father.

|

| Joseph C. Rickman Photo Courtesy Jullian Wall |

Joseph Rickman was twenty-one years old when he came to Kansas in 1871 with his mother, Mary Rickman Anderson, to homestead alongside his stepfather, David, sisters; America, Lucy and Tennessee, and brothers; Wayman, Jefferson, and Nathaniel.

|

| Rickman Anderson Brothers |

A few years later, Joe returned to Tennessee for a brief time. On October 26, 1874, he married Lucinda Paige. The newlyweds returned to Harvey County and Joe farmed. They had five children, the three girls Linnie, Estelle and Alta died very young and were buried on the Rickman homestead. Only the two boys, Clarence (b. 1884) and Ocran (b. 1889) lived to adulthood.

|

| Lucinda Paige Rickman Photo courtesy Jullian Wall |

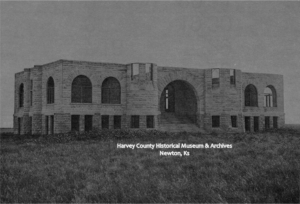

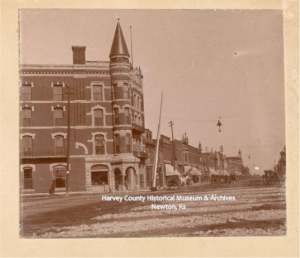

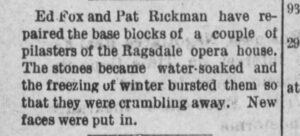

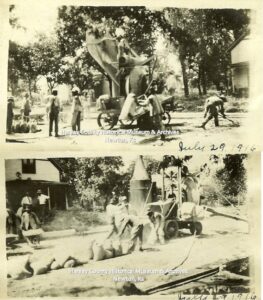

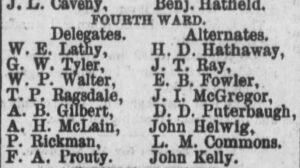

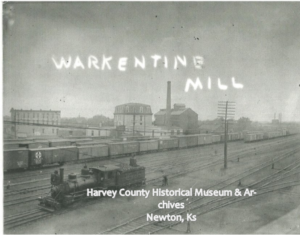

Joe and Lucinda had moved to Newton by 1885. The family was living at 424 w 5th and Joe was working as a laborer. Two years later, Joe is listed as a stone mason. According to family tradition, he helped to build the Warkentin Mill (today known as the Old Mill), and the Administration Building on the Bethel College Campus, North Newton. It is not known what other buildings Joe might have worked on over the span of his career. He also could have been part of the crew, along with nephew Pat Rickman, that laid the bricks for Newton’s streets.

|

| Warkentin Mill & Train Yards at Main & Third, Newton, Ks, ca. 1915 |

Constantly Increasing Business

By 1905 the family had moved to 114 W 4th Newton. While in Newton, Joe was also a businessman. In April 1900, he built a two story, seven room house on west 5th street. Joe also operated a restaurant and rooming house on west 4th street. In 1908, he needed to enlarge the building. The addition, located on the west side of the existing structure, was two stories high, 12 feet by 40 feet with a brick front. It was noted in the Newton Kansan that “Mr. Rickman finds the addition room needed because of his constantly increasing business.”

Bootlegging and Gambling

In March 1913, Joe was arrested, charged with “bootlegging and running a nuisance.” On the evening of May 15, 1913, authorities again raided Joe’s place. While he was not arrested this time, two “vagrants” J.E. Hill, white, and Katy Robbins, colored, were charged with vagrancy. They each had a bond of $15.00. Another patron of the establishment, “Big Boy” Taylor, paid the bond for Katie Robbins. Both Hill and Robbins failed to show up the next morning and forfeited the bond. The editor of the Newton Kansan noted that the new county attorney Hart was “going after the rough element” to “put a stop to the all the bootlegging and gambling” in Newton.

This was not the first time Joe Rickman had run afoul of Newton’s law enforcement. The area of W 4th and W 5th was the target of many police raids over the years. Rickman’s place was no exception.

In October 1903, the Newton police raided the “sporty colored population” on W 4th & W 5th. Joe Rickman was one among several brought in. He was “convicted of running an immoral resort and fined $50 and costs amounting in all to $61.50 which was paid.”

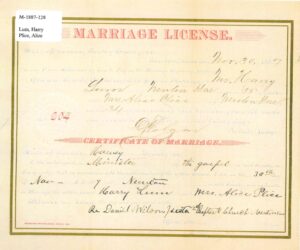

The most serious offense took place in 1909, when Rickman was put on trial for stabbing Arthur Childs in Harry Lum’s place. According to the Newton Kansan around 2:00 am “Joe Rickman stuck his stiletto into Arthur Childs” at Harry Lum’s place on W 4th. When witnesses along with Rickman and Childs were questioned, “they shut up like clams.”

The Kansan suggested that the altercation could have been over some money Rickman owed Childs. After Childs struck Rickman, Rickman “drew a knife and stabbed Childs in the right breast.” The knife hit a rib which resulted in a flesh wound and not a fatality. The reporter express frustration over the lack of cooperation of witness and even the victim Childs who treats the matter lightly and seems not disposed to sign a complaint.” Ultimately, his father, Frank Childs, signed a complaint against Rickman. After a trial at the end of March, Rickman was found guilty and sentenced by Judge Mears a fine of fifty dollars and sixty days in jail. Rickman appealed the case to the district court.

Joseph C. “Joe” Rickman died in May 1918 at the age of 68. Lucinda lived at 114 W 4th until her death in 1931 at the age of 76.

Clarence, son of Joe C. and Lucinda Rickman, owned and operated a “recreation parlor” locatedat 114 W 4th, Newton for a number of years, possibly from 1911 – 1913. Clarence was married to Jessie J. Greenboam, a native of London, England, on June 13, 1917. Their other son, Ocran, served in World War I. At the time of his death in 1955, he was living in Omaha, Nebraska.

During the month of February, in honor of Black History Month, we will be featuring related stories from Harvey County. Much of the information on the Rickman/Anderson/Grant family is based on oral traditions preserved by Marguerite Rickman Huffman & June Rossiter Thaw and research by Karen Wall. We are grateful for their willingness to share the stories of this Harvey County family.

Sources:

- Newton City Directories, 1885, 1887, 1902, 1905, 1911, 1913, 1918. Harvey county Historical Museum & Archives, Newton, Ks

- Evening Kansan Republican: 10 January 1900,27 April 1900, 9 August 1900, 1 April 190217 October 1903, 3 June 1910, 15 October 1910, 13 March 1913, 21 March 1913, 7 May 1913, 16 May 1913, 6 May 1914