by Jane Jones, HCHM Archivist

Kansas was a hotbed of reform movements during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. True or False?

True

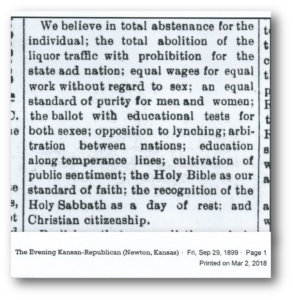

Temperance, Prohibition, Populist, Progressive and Women’s Suffrage were ideas debated and discussed by Kansans including Mary Ellen Lease, Carry Nation, Laura Johns, and Clarina Nichols. William Allen White and other Kansas newspaper editors joined the fray. National leaders, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Anna Shaw and Frances Willard, visited the state. An editor of our 1892 newspaper declared: “What other state can get so many things into her ‘political pot’ and keep the cauldron boiling and spattering at such a furious rate.” But something was the same—the Republican Party controlled the Kansas legislature.

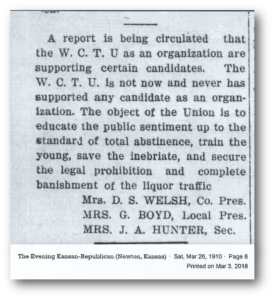

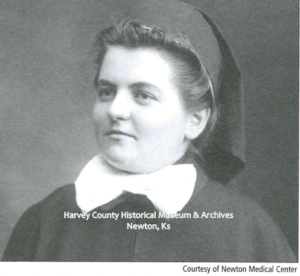

Not only did Ella Welsh fight for temperance, she also was a suffragist. Many members of the WCTU were also members of local suffrage associations.

States Control Elections

In the late 19th century white males over 21 could vote. Suffragists had to convince men, as well as some women, they should be able to vote in Kansas state elections. Middle and upper class women, who dominated suffrage and temperance clubs, were to be at home protecting man’s domain, not out in the public sphere. But, these boisterous women were changing that image. They wanted it all. Sound familiar?

At the National Woman Suffrage Association Convention in Washington, D.C. in February, 1876, the following questions were discussed.

- Are not women also citizens of the Republic-part of the people?

- On what just ground is discrimination made between men and women?

- Why should women more than men be governed without their own consent?

- Why should women more than men be denied trial by a jury of their peers?

- On what authority are women taxed while unrepresented?

- By what do men declare themselves invested with power to legislate for women?

By 1912, when women in Kansas received the right to vote, the suffragists had been part of a cause that had been simmering in the state for 50 years. Twice in 1867 and 1894 equal suffrage amendments were defeated at the polls. The first Kansas legislature in 1861 had given women the right to vote in school district elections. This concession was in a large part was won by Clarina Nichols an early advocate of abolition, temperance, and women’s suffrage.

The Kansas Equal Suffrage Association was formed in 1884. In Newton, “…a large number of women…” met at the Presbyterian Church on Aug 28, 1887 to prepare for a state suffrage convention to be held in Newton in October.

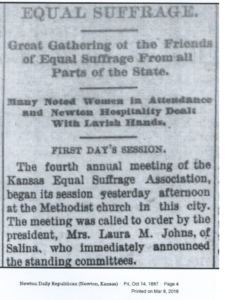

That convention was the 4th annual meeting of the state suffrage organization. The delegates stayed in the homes of the local suffragists. Susan B. Anthony enjoyed the hospitality of Mrs. Lehman (Lehman Hardware) and the first woman mayor of the United States, Mrs. Susanna Madora Salter of Argonia, Kansas stayed with Mrs. Schell.

The daily newspapers, the Republican and the Kansan were thanked “for their kindly notices in the interests of our cause.” The push for woman’s suffrage was so strong in 1887 that the legislature felt compelled to give women the right to vote in municipal elections, the first state to do so.

The support of a local editor was quite important to the cause of suffrage. Some editors around the state were not so helpful to the women suffragists. In comparing the number of votes cast by women as compared to men the Secretary of the State Historical Society concluded …“a much less desire to vote, on the part of women, than existed last year..”

Obviously, women needed the support of men to get a constitutional amendment passed for suffrage. At the meeting on June 13, 1888 at the home of Mrs. Frank Evans both ladies and gentlemen were invited. At the Harvey County convention of the Equal Suffrage Association cordially invited “all friends and those interested in the movement.” I assume that would include men. In March, 1892, at another state convention held in Newton a storm blew up the last evening of the convention. The newspaper reported:

“Young maidens and matrons, even grandmothers, walked blocks facing the storm to attend the meeting this afternoon. (Methodist Church at 7th and Main). A few men too, showed interest enough to leave their comfortable homes to be present. The missionaries are fine ladies, well able to present their peculiar views, but we do not think they made many converts in this locality.”

From the Emporia Republican came this observation, it was not helpful.

“Annie Shaw complains that Kansas women are a drawback to the woman suffrage cause because they will not vote. That is a little rough on the cause, of course, but it is a charming compliment to the Kansas women.” (Annie Shaw was an officer in the National Woman Suffrage Association)

From the Evening Kansan came these words:

“Do women want to vote?…some registered under protest…they registered in order to defeat the woman-politicians. From this view…we do not believe that 200 out of the 779 women registered in this city are believers in, or advocates of, woman-suffrage as a question of principle.”

These statements show how much opposition existed in 1893/94.

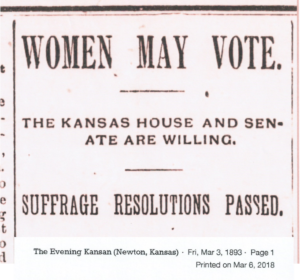

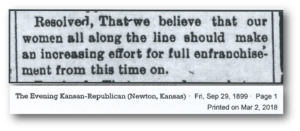

The resolutions passed the Kansas House and Senate and were submitted to the voters. Women’s suffrage was voted down. It was difficult to move the organization forward after this defeat.

In 1910, Mrs. Catharine Hoffman, President of the Kansas Suffrage Association suggested trying again in 1912. So began a push that was even more organized and more focused. They were learning by previous mistakes and were asking politicians how to run a successful campaign. Ella Welsh became involved in this campaign, taking on a leadership role as she had for the WCTU.

The Topeka Daily Capitol received a news release that stated “Harvey county was organized by the women suffragists this afternoon…” (December 12, 1911). Mrs. Ella (D.S.) Welsh was elected president. She presented a program on suffrage to the teachers of Harvey County and asked them to approve a resolution that as a body the teachers association favored equal suffrage. “The resolution was adopted.”

A report from Mrs. John Mack in a special edition of the Topeka newspaper on October 27, 1912 told of the activities of the Harvey County Suffrage Association. Mrs. Noble Prentis met with club women and it was decided to have suffrage headquarters on Main street. Members were to poll the towns and the county. The results of the poll indicate a large number of voters favor the amendment. Mrs. Prentis also spoke to the student body and faculty of Bethel College, as well as, Newton High School students. “Colored people” listened to Mrs. Prentis at one of their churches and promised support. “Mrs. D.S. Welsh… has been at work all of the summer distributing literature and buttons at every large gathering.” Think of what these women would have accomplished with the use of the Internet and social media!

On election night (November 5, 1912) there was a party in Newton. “Forget your troubles when you enter the auditorium, and be prepared for any result that may be announced.” This time woman’s suffrage for the state of Kansas was secured. Kansas was the 8th state to ratify an equal suffrage amendment. The count showed 175,246 votes for and 159,197 against. A suffrage tea was held at the home of Mrs. Gaston Boyd for supporters and non-supporters of the Kansas equal suffrage amendment.

But, work was not done. Barely adopted in 1920, the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution prohibited states and the federal government from denying the right to vote to citizens of the United States on the basis of sex.

I recently read The Paris Wife by Paula McLain. A passage caught my attention. The book is about the first marriage of Ernest Hemingway to Hadley Richardson. Hadley is afraid she is not a “modern woman,” a term describing the younger woman emerging in the 1920s. She says:

“It was ironic to think that nearly all the women I knew now were the direct benefactors of the suffragette work my mother did decades ago, right in our own parlor, while I curled up with a book and tried to be invisible.”

So ladies, when you vote this November, 2018, remind yourselves of all the women before you like, Ella Welsh, who fought for your suffrage.

SOURCES:

- Newton, Kansas Newspapers: Kansas Historical Society. newspapers.com

- Harvey County News. 2 Feb 1876

- Newton Daily Republican. 28 Aug 1887

- The Evening Kansan. 14 Oct 1887, 19 Jan 1888, 14 Feb 1888, 27 Apr 1888, 13 Jun 1888, 4 Mar 1892, 14 Mar 1892, 15 Mar 1892, 22 Mar 1892,3 Mar 1893, 4 Mar 1893, 31 Mar 1893

- The Evening Kansan-Republican. 24 Jun 1912, 5 Nov 1912

- Topeka, Kansas Newspapers: Kansas Historical Society. newspapers.com

- The Topeka Daily Capital. 13 Dec 1911, 27 Oct 1912

- Stratton, Joanna L. Pioneer Women: Voices From The Kansas Frontier. Simon & Shuster, New York. 1981. p. 253-265 (HCHM Library)

- Edwards, Rebecca. “March Murdock and the ‘Wiley Women’ of Wichita: Domesticity Disputed in the Gilded Age.” Kansas History A Journal of the Central Plains Vol.25 No. 1 Spring 2002. KSHS Topeka, KS Allen Press Lawrence, KS pp. 2-13.

- Drury, James W. and Associates. The Government of Kansas. University of Kansas Press. Lawrence, KS. 1961. pp. 35-36.

- Smith, Wilda M. “A Half Century of Struggle: Gaining Woman Suffrage in Kansas.” Kansas History A Journal of the Central Plains. Vol. 4 Number Two Summer KSHS Topeka, KS Allen Press Lawrence, KS

- Gehring, Lorraine A. “Women Officeholders in Kansas, 1872-1912.” Kansas History A Journal of the Central Plains. Vol. 9 Number 2 Summer KSHS Topeka, KS Allen Press Lawrence, KS

- Caldwell, Martha B. “The Woman Suffrage Campaign of 1912.” Kansas Historical Quarterly. Aug 1943 No 3. KSHS Topeka, KS

- Wikipedia: Free Encyclopedia. “Clarina I.H. Nichols” and “Nineteenth Amendment” (en.wikipedia.org)

- Francis, Roberta W. Chair, ERA Task Force National Council of Women’s Organizations. “The Equal Rights Amendment: Unfinished Business for the Constitution. The History Behind the Equal Rights Amendment.” http://equalrightsamendment.org/history.htm.