by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

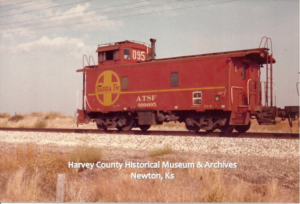

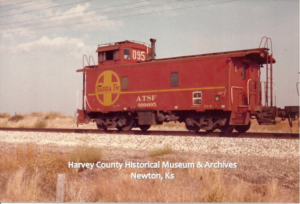

For years, the distinctive red train car that almost looked like a house on tracks signaled the end of the train. Today, the caboose is a a memory and the end of a train is marked with a blinking light on the last car.

Santa Fe Caboose, 999591, August 1987.

The Waycar, commonly called the caboose, signaled the end of the train for years. The waycar served a very particular purpose and was used almost exclusively on trains in the U.S.

First used in the 1830s to house trainmen, the caboose was was the “home away from home” for conductors. The earliest way cars were little more than “shanties built onto boxcars.”

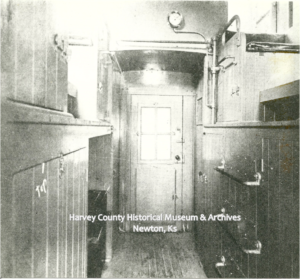

Way Car #1951, old style, 1937.

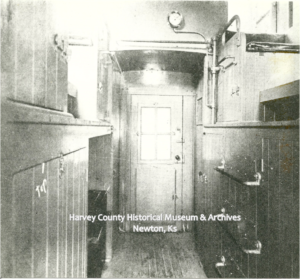

Inside Waycar No 1951 — 1937.

Conductors were assigned a car and many added touches from home including curtains and family photographs.

Interior Way Car #1951, cupola end.

Items included in the above photo: pantry, 50 gallon water barrel, restroom, broom and coat closet.

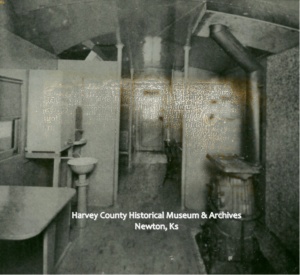

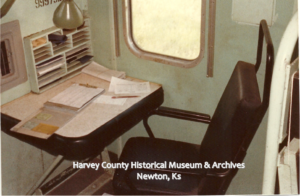

Photo below shows the ‘bunk end,’ or living and sleeping area. Water tanks with washing and drinking water, the conductors desk and four bunks a table with seats made of wooden boxes that held additional supplies.

Interior of Way Car #1951, Bunk End

The brakeman and flagman rode in the caboose. When the engineer whistled that the train was to slow down or stop, one brakeman worked his way toward the front of the train twisting the brakewheels located on the top of the freight car. Another brakeman worked his way from engine to the back. When the train stopped, the flagman would exit the caboose and place lanterns, flags and other warning devices a safe distance from the train to warn and stop any other approaching trains. As technology improved these jobs changed. For example in the 1880s, air brakes meant that the brakeman did not need to manually turn the brakewheels.

AT&SF Engine 1012, ca. 1905. Brakeman – A.F. McDowell & E.C. Humphfres; Engineer – H.B. Mell; Conductor- E.G. Pusey; Fireman – R.D. Beach

The Cupola

The cupola served as a lookout for the the trainmen. First used in 1863, a conductor discovered that he had a better view of the entire train if he sat on boxes and peered through a hole in the roof. This idea led to the improved design for observation of the train. A conductor was able to sit up in the cupola for a panoramic view.

Waycar #999095 — ca. 1960s

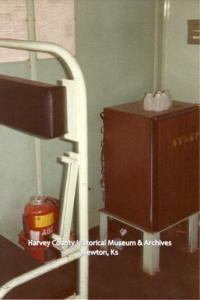

Everything necessary for day to day living of the crew was stored in the caboose.

Way Car 999095, Hurley Collection.

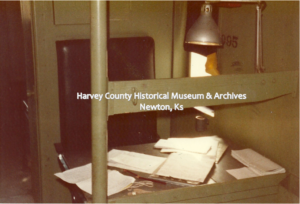

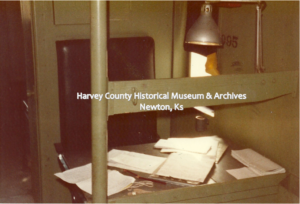

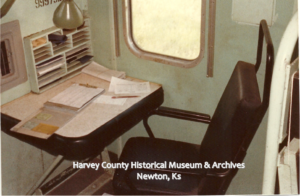

Interior of Way Car #999095, conductor’s desk.

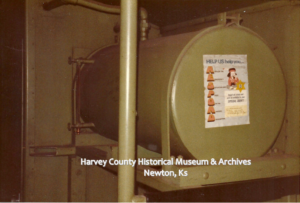

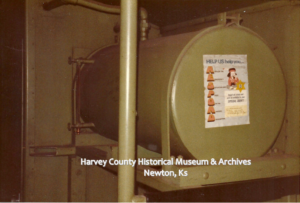

Water Storage Tank.

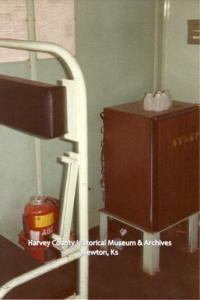

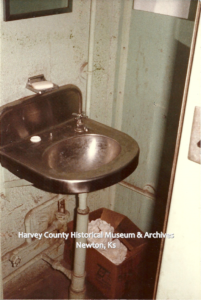

Waycar #999752 Interior

Way Car Interior, #999752, refrigerator.

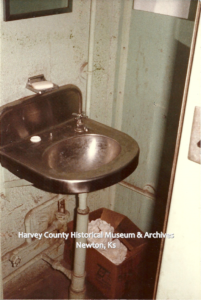

Way Car #999752 interior, wash basin in wash room.

Way car interior, Conductor’s Desk

Technology and the Caboose

Eventually, due to improved technology and a desire for safer work conditions, the way car or caboose became obsolete. As trains became longer and rail cars became higher, it was no longer practical for the conductor to see the entire train from the vantage of the cupola. Improved detectors or “hotboxes” meant that equipment could be checked with more efficiency and reliability by the conductor. With the introduction of computers, the need for a place to store paper and records was eliminated.

Today, the end of the train is monitored using a remote radio, or “End Of Train” (EOT) that fits over the rear coupler and a caboose at the end of a train is rare.

#HarveyCountyTravels

Sources:

- Hurley, L.M. ‘Mike.’ Newton, Kansas: A Railroad Town – History, Facilities & Operations, 1871-1971. N. Newton, Ks: Mennonite Press, 1985.