by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

Note: For the month of May we are focusing on the people behind the trails, rails and buildings that form the foundation of our community. For this post, I am indebted the Newton Public Library oral history project from 1977. On May 3, 1977, A. W. Holt interviewed Antonio Gomez about his experiences as a child in Mexico, the trip to Kansas and what it was like for his father working on the railroad and later for Antonio himself. Antonio was 10 when his family came to Kansas as one of the first Mexican American families to settle permanently in Newton, Ks. The transcript for the interview, along with several others, is available at the Newton Public Library, Newton, Ks.

As much as possible, I let Antonio tell his story.

Coming to Newton

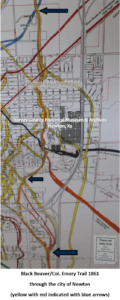

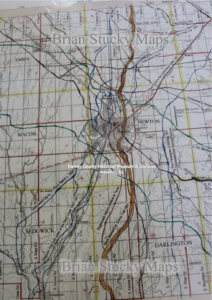

In 1905, 10 year old Antonio Gomez boarded a train with his family and started the long journey that would change his life. To get to Walton Kansas, from Villa Obergon in Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico, the family first went by “three cars and the express in a small engine.” At El Paso, TX, they boarded the train that would take them to Kansas. Antonio later recalled the journey noting, “I came here with my father and my stepmother in 1905.”

Antonio described his impressions of Newton.

“There was not any pavement when I came here on Main Street, and I remember how . . . when they passed the track, those horses, cars of horses and horses left much mud, all that. Then they brought a man with a little car cleaning all that the horses had thrown, the earth and all in that.” He also recalled that the buildings were “littler . . .and then some . . . were completely redone . . renovated from little to bigger.”

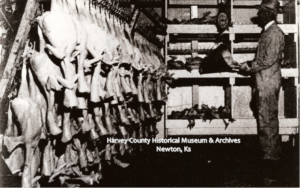

The Gomez family was comfortable in Villa Obergon, where the elder Gomez was a butcher and Antonio was able to attend six months of school. Antonio’s mother, Nicolasa (Varrientos) Gomez died, and his father remarried. Mostly life was normal. Despite this, Margarito must have felt there were more opportunities for his young family in the United States.

Unlike many other Mexican men that worked for the Santa Fe Railroad in the early 1900s, Margarito did not want to work seasonally. Traditionally, the laborers would go to the US to work for the railroad during the summer months to earn money and return to Mexico for the winter. Margarito, however, was of the mind that if he was going to go work in the United States, the family would go with him and stay. The family, which included Margarito, his 2nd wife, Antonio and a sister, came to Kansas.

“Because He was in the Free Air”: Margarieto Gomez

Margarieto found work with the railroad that summer, but, because he wanted to stay past the summer season, he was forced to move to Wichita to find construction work. The family moved to Wichita. They lived in a tent all winter and a very cold March. In a 1908 report, March 1906 was recorded as the coldest March in the middle Plains in 40 years. In May, they returned to Newton.

Gomez recalled one other time the family had to move for his father’s work. They spent eight months in Herrington, Ks, while Margarieto worked for the railroad. Ultimately, Margarieto found regular year round work with the Santa Fe Railroad in Newton at the roundhouse and the Gomez family able to put down roots. At that time, he was paid ten cents for ten hours of work. Eventually, the elder Gomez changed to section track work, which he enjoyed more “because he was in the free air.”

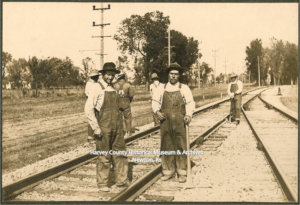

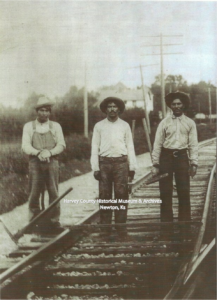

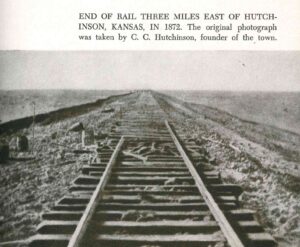

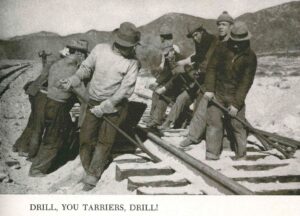

Track men or section workers lived along and maintained a six to eight mile section of the railroad. Most of their responsibilities included reinforcing weak railbeds, tapping down loose pins, and clearing debris from the track and the area around it. They worked six days a week for ten hours. Typical pay was $1.10 to $1.25 a day.

Marshall, photos. Section workers on the job. Photo is not taken in Kansas, but illustrates the type of labor these men did.

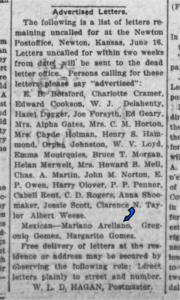

Margarieto also kept in contact with his family in Mexico. His name frequently appears in the newspaper under the section “Advertised Letters” indicating he had mail to pick up.

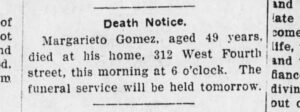

Margarieto Gomez, husband, father, adventurer, dedicated employee worked until December 1915 when he died at the age of 49 years old.

Margarieto’s second wife died from influenza in 1918, and 23 year old Antonio remained with the recently orphaned children “two little girls (chamaquitas) and two boys (chamacos), they were four. One year later, their grandparents in Mexico sent for the children to live with them.

Beginning a family: Antonio and Yrene Gomez

Shortly after the children went back to live with their grandparents, Antonio married Yrene (also spelled Irene) Pedrosa. The couple had six sons and two daughters.

“I began to work about the age of sixteen:” Antonio Gomez

Antonio Gomez went to work for the AT&SF at the age of sixteen. He recalled that they did not want to give him a job, “but, always my father signed, and they gave me work.” Antonio worked in the roundhouse and described his responsibilities.

“The roundhouse had thirty-seven housings where they enter the engines. . . and extinguish the fire. Then there was one [person] that changed the water and washed and flushed them. I worked there when I was very young. Then, one put all the flushers in, return position and we filled them with water and then there was a man who started the fire and then they began to have steam and leave, with the steam on the outside.

I began to work releasing the steam from the engines, filled on return with water. . . .that was my first work I did there. Then I was working with the boilers for six month and stoked the boilers to give steam for the roundhouse and to the depot. . . from there I changed to the coal chute. There was in the coal chute . . . sand and coal for the machines. . . well I remained working all those years from ’15 to ’64.”

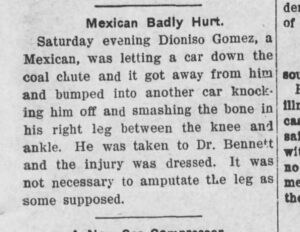

“It was not necessary to amputate the leg”

The railroad was a dangerous place to work. Although Dioniso Gomez may or may not be connected to the Antonio Gomez family, his story illustrates the dangers faced daily by these men. Due to a mishap with some of the cars, his leg was crushed. The brief announcement in the paper concluded with “It was not necessary to amputate the leg as some supposed.”

Luckily, Antonio Gomez seems to have escaped serious injuries in his work. The loss of fingers from coupling cars or any other dangers working with the big engines was a constant concern.

“I worked continuously”

Antonio Gomez worked for the railroad from 1915 to 1964 or as he put it “I worked continuously without leaving . . . thirty-four years.” He was one of the first Mexican American children to come and live permanently in Newton, Ks. With only six months of school, he did not know how to read and write, but he learned. Largely self taught, he did recall a man who him taught the basics of reading and writing. The rest he learned by reading newspapers and books.

Antonio B. Gomez died April 11, 1983. He is buried in St. Mary’s Cemetery.

Sources:

- Gomez, Antonio interviewed by A.W. Holt, 3 May 1977. Newton Public Library, Newton, Ks. Call Number K K687.292

- The Yearbook of Agriculture. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1909. Google Books.

- Ducker, James H. Men of the Steel Rails: Workers on the Atchinson, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad 1869-1900. University of Nebraska Press, 1983.

- Marshall, James. Santa Fe: the Railroad that Built and Empire. New York: Random House, 1948.