Originally posted Wednesday, February 20, 2013 A Front Row Seat to History

This post continues the story of Charles Schaefer of Sedgwick, Ks. For more stories see Part 1 & Part 2.

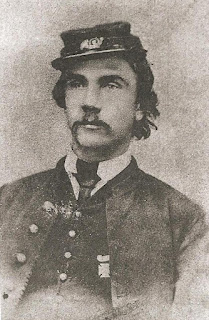

Most of us will never have the chance to meet the President of the United States, but one Kansan did. In later years, Schaefer recalled his experiences as a soldier in the capitol during which time he met President Lincoln.

Front Row Seat to History: Meeting Lincoln

In his handwritten notebook of remembrances, Schaefer related his impressions of President Abraham Lincoln.

“A very queer man. . . Personally there was much good about him which was alright in civil life, but in war was not good.* I met him face to face between the White House and Treasury Building, stood at attentions and saluted as was proper. He certainly was the homeliest man I ever saw; stove pipe hat, big clothing that did not fit. But I gave him a square good look in the eyes and I do not believe I ever saw a kinder and sympathetic [person]. I rather pity him, he looked so lonesome and sorrowful. . . Of course, I saw him several times at Grand Reviews.”

Buried Secrets

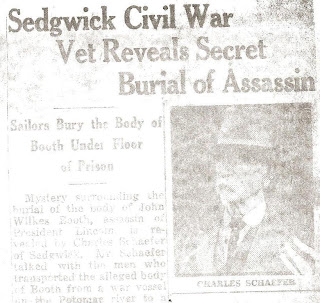

Schaefer also had stories to tell about his time in the army. In this faded clipping from an undated Wichita Eagle, Schaefer recalled an incident from the close of the Civil War related to the assassination of President Lincoln.

|

| Newspaper clipping in the Schaefer Scrapbook Sedgwick Historical Society Sedgwick, Ks |

“Eight sailors of the U.S. navy detailed to have charge of a boat kept in readiness for the governments use. . . . One night they had been called upon to take their boat and row upstream til they found a ship on the other side of the Potomac. . . . When the drew alongside the ship, they were stopped and a box, casket-shaped, was lowered into their boat and they were ordered to return to shore.”

The men were sure that they recognized the room as one in the Old Penitentiary and they were convinced that the body was that of John Wilkes Booth.

Schaefer concluded his story by noting:

“I promised I would not repeat the information since they were under orders to keep still. I kept my word until this long distant date when telling can do no harm.”

Tall Tale?

| John Wilkes Booth’s Autopsy http://rogerjnorton.com/Lincoln83.html |

Sources:

- Schaefer Scrapbook, Sedgwick Historical Society, Sedgwick, Ks

- http://rogerjnorton.com/Lincoln83.html;

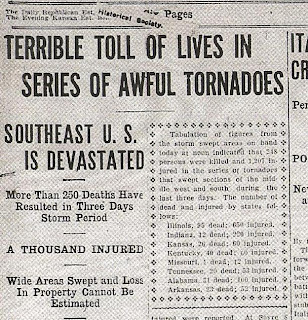

Dewey Faw was the 18 year old boy who was killed. He and his brother Floyd Faw were raised by their Aunt Caroline Coble after their mother died in 1902. Dewey was in the house and he opened the door when he heard the noise. He couldn’t escape. Floyd was one of the lucky ones who made it to the cellar. Four years after the tornado Floyd married his nurse Ivalee Harvey who cared for him while he was recovering from his injuries in the hospital. They were my grandparents.