by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Archivist/Curator

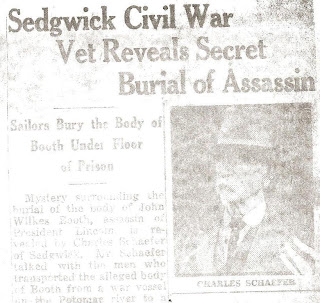

Before settling in south central Kansas in the future town of Sedgwick, Charles Schaefer led an interesting life. At the age of ten he left home and became a part of the frontier army at Fort Leavenworth and traveled throughout the territory as a scout. Later in life, Schaefer recorded his memories of his experiences and the people he met during this time of his life. His account of spending time at Maxwell’s Ranch in New Mexico closely matches other first hand accounts encounters with Lucien Maxwell right down to where he kept his money. Lucien B. Maxwell was a colorful man and today is one of three men who have been the largest private landowners in U.S. history.

For more of Charles Schaefer’s story see part one features Schaefer’s early life, and part 2 his Civil War experiences and later life.

“An Honest trader whose handshake connected three cultures.”

Col. Fauntleroy, along with Kit Carson, led several expeditions against the Apaches in 1859-1861. Young Charles Schaefer was along on some of these missions. It was during this time that he became acquainted with rancher and entrepreneur Lucien B. Maxwell. Before his death in 1875, Maxwell was one of the largest private landowners in United States history, at one point owning over 1,700,000 acres.

In the early days, Maxwell’s Ranch served as the headquarters for the Ute Agency with the government stationing a company of cavalry there to control the Plains Indians. The Ute regarding Maxwell as a friend.

In the summer of 1867, Schaefer spent a “delightful two weeks with Maxwell” and years later he described the man and his experience visiting the Ranch giving us a glimpse of the west before settlement.

A Great Ranch, A Place of Beauty

According to Schaefer, Maxwell’s Ranch was to his surprise a “great ranch, a place of beauty.” Schaefer described Maxwell’s Ranch as a “Manor-House.”

“The kitchen and dining room of his princely establishment were detached from the main residence. There was one of the latter for the male portion of his retinue and guests of that sex, and another for the female, as in accordance with the severe and strange Mexican etiquette, men rarely saw a woman about the premises. Only a quick rustle of a skirt or a hurried view or a hurried view . . . before some window or half open door, told of their presence.”

Maxwell entertained often and Schaefer observed; “the greater portion of his table service was solid silver, and at his hospitable board there were rarely any vacant chairs . . . “ The ranch was located along the “Old Trail” and a frequent stop for overland travelers. Schaefer also recalled that “at all times and in all seasons, the group of buildings, houses, stables, mill , store and their surrounding grounds, were a constant resort and loafing place of Indians.” A large “retinue of servants [was] made up of heterogeneous mixture of Indians, Mexicans and half-breeds.”

|

| Aztec Grist Mill

Established by Lucien Maxwell 1865-1870 |

Schaefer noted that Maxwell “possessed a large and perfectly appointed grist mill which was a great source of revenue.” Maxwell was a wealthy man and Schaefer noted that he was “never without a large amount of money in his possession. He had no safe . . . only the bottom drawer of the old bureau in the large room” that was never locked. Guests were free to roam the grounds with no extra precautions taken to safe guard the gold, silver and government checks Maxwell kept in the drawer. He was said to keep as much as $30,000 in cash in an unlocked dresser drawer.

Schaefer recalled that he once suggested that Maxwell should purchase a safe of some sort, “but he only smiled, while a strange resolute look flashed from his dark eyes, as he said: ‘God help the man who attempted to rob me, and I knew him!'” * While Maxwell had a reputation for hospitality, he could also be brutal. Stories of imprisoning thieves without food or water and flogging servants he was not pleased with were not uncommon. Perhaps this reputation kept would be thieves honest.

Of the man himself, Schaefer recalled the following story;

“Frequently Maxwell and Carson would play the game of Seven-up for hours at a time . . . Kit usually the victor . . Maxwell was an inveterate gambler . . . His special penchant, however, was betting on a horse race, and his own stud comprised some of the fleetest animals in the territory.”

During the time that Schaefer spent at Maxwell’s Ranch, gold was discovered “and adventurers were beginning to congregate in the hills and gulches from everywhere.” According to Schaefer, this discovery led to the ruin of “many prominent men in New Mexico, who expended their entire fortune in the construction of an immense ditch, 40 miles in length from the Little Canadian or Red River, to supply the placer diggings in the Moreno Valley with water. . . The scheme was a stupendous failure.” Maxwell was one of the men who lost a great deal on this venture.

Charles Schaefer truly met many interesting people throughout his long life.

Notes:

- Col Henry Inman, also a frequent visitor to Maxwell’s ranch, told the exact same story in his memoirs. https://www.legendsofamerica.com/nm-maxwell/

Sources:

- “Autobiography Document #2” Charles Schaefer File, Sedgwick Historical Museum, Sedgwick, Ks.

- For more information on Lucien B. Maxwell, his life, land grant and the gold found at Baldy Peak:

- http://www.newmexicohistory.org/filedetails.php?fileID=24150

- Ryus, William H. “Lucien Maxwell by a Santa Fe Trail Driver.” https://www.legendsofamerica.com/nm-maxwelltale/