by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Aarchivist/Curator

On July 28, 2001, Ed Rawlins, a man thought to be the oldest porter in Newton, Ks, died. His death marked the end of an era in Newton’s railroad history. For forty years, 1934-1974, he worked for the Santa Fe Railroad as a porter. A job that he quietly did day after day, along with many other black men, with no hope of advancement. Rawlins was also part of a landmark Civil Rights case to fight this discrimination.

The Hours of Service are Barbarously Long”

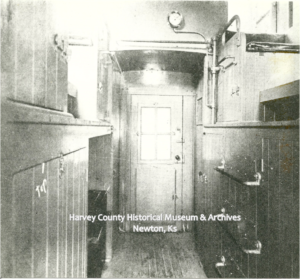

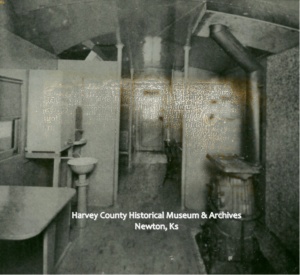

Railroad porter was a profession of status in the black community and a ubiquitous part of traveling on the railroad for about 100 years. Following the Civil War, traveling on the railroad gained in popularity and people began to demand services. Like Fred Harvey with his Harvey Girls and Harvey Houses, where excellence was demanded, George Pullman pioneered excellent service in the luxurious sleeper cars. These “palace cars” included everything one could find in a good hotel – comfortable beds, air conditioning, and even chandeliers. Gourmet meals were served and travelers were pampered. Pullman needed one more thing, people willing to provide the service and do sometimes menial work without complaint.

Pullman discovered the perfect work force to maintain this elegance – ex-slaves. Although the job was held in high regard in the black community, in reality the Pullman porter was one of the most exploited jobs in the country in the mid-20th century. Porters worked very long hours for low pay and performed tasks that most unskilled white workers would not.

Porters were expected to be at the beck and call of the passengers. They often worked 20-hour shifts with only three to four hours of sleep in between. There was also a certain amount of unpaid prep work they were expected to complete. One observer noted that “the hours of service are barbarously long.” (Berman) In addition, they paid for their own food and supplied their own uniforms.

A survey conducted March 1934-February 1935, illustrated the poor pay. Those conducting the study discovered that the annual income of all porters in the survey was $880. The weekly income was $16.02. In comparison, the average weekly wage of all workers in manufacturing industries in the US in 1934 was $19.12, with wages reaching $23.19 in New York. (Berman)

In a particularly demeaning twist, porters were often addressed as “George,” and not their real names, reflecting their employers first name. A practice begun during slavery when slaves were known by the first name of their owner. (5 Things)

There were positives to the job. Porters traveled all over the U.S. They learned to know wealthy, influential people and what was going on in the larger world. They brought this information home with them to share in their churches and communities.

At its peak, the Pullman Company was the largest single employer of black men in the United States — employing 20,000. (5 things)

Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters

In 1925, with the help of a prominent labor rights advocate, A. Philip Randolph, the porters were able to begin the process of unionizing. There was resistance from the Pullman Company and even black community members, but they persisted. After a decade, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was established becoming “the first African-American labor union to successfully broker a collective bargaining agreement with a major corporation.” (5 Things)

The Pullman porters in the 1920s laid the groundwork for the civil rights movement by forming the first black labor union. In the 1960s, the union gave leadership, money and venues to the civil rights movement and the struggle of the porters for equal opportunities. (Seeking)

By the 1960s one thing was glaringly evident, even though they were qualified, black porters were never promoted to better positions.

“I was qualified to do the work. They just didn’t let me do it.”

Joe Sears was a quiet, mild-mannered man who faithfully and diligently worked for the Santa Fe. He had started his career with the Santa Fe in 1936 at the lowest level of employment – the chair-car attendant. He was promoted to porter. He took the necessary classes and passed tests required for a promotion to brakeman in 1936 hoping to move to a better paying position. Over the years, Sears learned every job on the train and often trained those who became porters, brakemen, firemen, conductors and engineers. He applied for promotions to brakeman over the years but was always refused. He was told “You can’t become a brakeman until your skin changes color.” (Roe)

In August 1965, Sears returned home from his normal Chicago-to-Kansas City run and was watching TV when news of the Watts Riots broke. Sears later recalled that he “knew those people on that TV screen. He shared their years of being invisible and beaten down. He shared their anger.” He continued, “I leaped up otta my chair – I’ll never forget it – I said, ‘If I was there, I’d burn some of ’em too!'” Sears recalled his frustration at never getting a promotion, noting “his bosses refused to promote him, ‘They never argued about the fact that I was qualified to do the work. They just didn’t let me do it, that’s all.'” (Roe)

“Charging racial discrimination”

The next morning, he again applied for the brakeman’s job and was denied. The age limit was 35, he was 53. Sears also had learned about the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that made discrimination against the law and people were encouraged to report it. On March 8, 1966, Joe Sears drove to Topeka to the Commission on Civil Rights and filed a complaint against Santa Fe and the United Transportation Union and began a 27 yearlong battle for compensation. (Roe)

October 7, 1972, Sears was notified by Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) that he was entitled to sue the railroad and the union under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act. On November 1, 1972, lawyer Terry Paup filed suit in the US District Court Wichita to stop AT&SF and the United Transportation Union from discriminating against blacks and to collect damages. A class action lawsuit on behalf of Sears and 72 other black porters employed by Santa Fe Railroad was filed.

On August 25, 1975, Joe Sears, the last Santa Fe porter, retired. Sears had worked for the Santa Fe for 39 years. He never received a promotion. His fight with the Santa Fe was not over.

On December 1, 1982, Sears and “all other persons similarly situated” won their case. The decision was then appealed to the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals in Denver in March 1984.

Finally, in December 1993, 27 years after the first filing, the Sears and 273 other men received their money. The court awarded $24.5 million to 273 current and former railroad employees. Seventy-three were former train porters and 200 former chair-car attendants. They successfully sued their employer, Santa Fe Railway and the United Transportation Union, “charging racial discrimination and seeking damages commensurate with the wages they lost by being barred from white-only jobs.” (Roe)

Among the seventy-three porters were three men from Newton, Ed Rawlins, Baylon Thaw, Sr, and Ray Wagner.

Newton Men

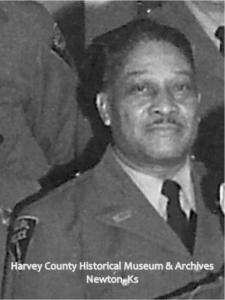

Edward W. “Ed” Rawlins

Ed Rawlins was born in Hutchinson on April 16, 1909, and attended grade school at Sterling. After graduating from Sterling High School in 1929, he attended Pittsburg State University studying business. He also learned the craft of upholstery and refinishing furniture. He married Mary M. Landrum in February 1935. They were married for 66 years. In his adult life, he attended Halls Chapel AME Church in Newton, Ks and at the time of his death, he was the oldest member. Rawlins was active in the church at all levels serving as trustee, lay president, and singing in the choir. He was also active in the community as a member of the Rising Sun Masonic Lodge, No 27 and working as a Newton Police Reserve for many years. He worked for the Santa Fe for 40 years as a porter with no chance of advancement. Rawlins was awarded $123,031.57 with interest earned from 1982-1984 the total amount $140255.99.

Rawlins died on July 28, 2001.

Baylon Kirkpatrick Thaw Sr.

Baylon Thaw was born April 10, 1916, to Harry and Georganna White Thaw. His siblings included Booker T., Jack A., Harold A., and Georganna C. Thaw Gray. His half siblings included Omine and William Beard. He grew up in Harvey County and married Monterie L. (Cox) Thaw. They had one son, Baylon Thaw, Jr. In 1950, the Thaw family moved to Kansas City, Jackson County, Missouri. Thaw worked for the Interstate Transportation Railroad Station as a porter. He died 7 September 1972. In 1993, his portion of the settlement was $131,162.64 with interest the total came to $149,252.41.

Ray Wagner

Ray Wagner was born June 3, 1893. He was awarded $33,931.31 with interest $38,681.69. (Lewis to Byrd) Wagner died in April 1981.

Sources

- Sears v. Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Ry. Co., 454 F. Supp. 158 (D. Kan. 1978) :: Justia

- Sears v. Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Ry., Co., 749 F.2d 1451 | Casetext Search + Citator

- Sears v. Atchison, T. S. F. Ry. Co., 645 F.2d 1365 | Casetext Search + Citator

- Chester I. Lewis to Verda Wagner Byrd, letter, 2 March 1984. Letter shared with HCHM curator includes the names of the men in the suit and the amounts awarded.

- Berman, Edward. “The Pullman Porters Win” The Nation 21 August 1935.

- Seeking the last of the Pullman Porters – Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen

- Five Things to Know About Pullman Porters | Smithsonian

- BLACK HISTORY MONTH | Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters legacy still lasts 100 years after founding | News | tribdem.com

- Roe, Jon. “One Porter’s Long Ride to Racial Justice.” Wichita Eagle, 5 December 1993.

- Thaw, Baylon Kirkpatrick, Find A Grave, #212648021 includes an undated obituary.

- U.S. Census 1930, 1940, 1950