By Kristine Schmucker, Curator

Previously posted on our old blog site on March 28, 2013

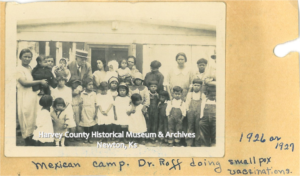

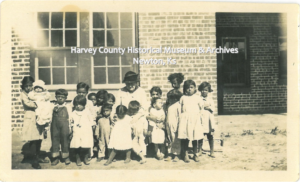

We are so grateful to the health care workers that are working tirelessly during this time of a global pandemic. Harvey County has a long tradition of caring. Early on the women of Harvey County played a leading role in providing health care for the community. Dr. Lucena Axtell worked with her husband, Dr. John T. Axtell, to establish Axtell Hospital as the first health care facility in Newton. Harvey County women were also leaders in the field of public health. In the 1920s, Miss Johanna Conway, along with a group of women from St Mary’s Catholic Church worked on education for the “Mexican Camps.” In 1916, Harvey County was one of the first Kansas counties to establish a Public Health Nurse. Initially, the Public Health nurses was under the direction of the Women’s Auxiliary of the Bethel Deaconess Hospital, Newton.

Sister Anna Gertrude Penner, a Deaconess with the Bethel Deaconess Hospital, served as the first Public Health Nurse from 1916-1921. In this role, Sister Gertrude joined a national movement started by Lillian Wald in New York that sought to educate and care for the health of the community and especially the poor.

What was a Deaconess in the Mennonite Church?

The Deaconess movement that started among south central Kansas Mennonites came at a unique time when needs in health care and desires to devote one’s life to caring for others came together for several women in the Mennonite Church. June 8, 1908 Sister Frieda Kauffman, Sister Ida Epp, and Sister Catherine Voth, after completing their training, were the first ordained Deaconesses of the Mennonite Church. This was during a time when women were not allowed to attend “Brotherhood meetings” or vote on church matters.

Deaconesses were not paid wages, rather all of their needs were met by the “motherhouse” and any wages received from other sources went to a common account at the sponsoring organization. In Newton, the Bethel Deaconess Hospital provided the Deaconess with a home, full maintenance, monthly pocket allowance, an annual vacation allowance, and opportunities to attend institutes, conventions, and take post graduate work with expenses paid.

Sister Anna

Born October 4, 1886 near Hillsboro, Ks, Anna Gertrude Penner was the second of fourteen children in the family of Rev. Heinrich D. & Katherine Dalke Penner. Education was important to her parents. In addition to serving as a minister for the Hillsboro Mennonite Church, Rev. Penner taught at several schools in the area including the elementary school in Lehigh, Ks, Bethel College, North Newton from 1893-1897 and the Hillsboro Preparatory School from 1897-1913. No doubt he instilled this value in his children and encouraged their education. As the second oldest, Anna would have also been called on to assist her mother with the younger siblings as she grew to adulthood. Perhaps these influences led her to consider dedicating her life to educating and caring for the sick and infirm.

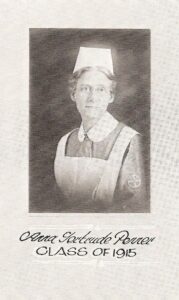

Anna Gertrude Penner graduated from the Bethel Deaconess Hospital School of Nursing in Newton, Ks in 1915.

Following her graduation, she took four months of additional classes in Chicago specializing in public health, paid for by the Women’s Auxiliary of the Bethel Deaconess Hospital. Upon her return to Newton in 1916, she became Harvey County’s first ‘visiting nurse’.

On October 1, 1916, at the age of thirty, she was ordained as a Deaconess by her father Rev. Heinrich D. Penner. For the next fifty years Sister Anna served the Newton community in a variety of ways. She served as the public health and school nurse until 1921, when she serviced as a R.N. at Bethel Deaconess Hospital, Newton. She also taught future nurses and finally served as a receptionist at the Bethel Student Nurses Home. Rev. Penner also remained a supporter of the Deaconesses at Bethel Deaconess Hospital, serving as a teacher and spiritual advisor. He also published several educational pamphlets for use in classes.

Public Nurse

As a Public Health Nurse, Sister Anna cared for the sick, but more importantly, she worked to educate households on preventative measures. She provided information and care to new mothers in their own homes.

In 1917, Sister Anna expanded her duties to include school nurse for the Newton schools. To assist her, Sister Anuta Dirks joined her as public health nurse for the county.

According to Sister Anna the role of the public health nurse was more than just caring for the sick patient, they must “look for causes outside the patient and family, and see what role the community plays in the matter of health and disease. It is possible . . . that neither the patient nor his family is to blame for having typhoid fever or tuberculosis or even for being poor and ignorant.”

At first, the Public Health Nurse was supported solely by the Women’s Auxiliary of the Bethel Deaconess Hospital. They provided the funds for Sister Anna to attend the additional classes in Chicago. Although after her ordination, Sister Anna did not receive any salary for her work, there were other expenses.* The Auxiliary requested that the Newton City Commission help pay for the support of the Public Nurse. In 1918, the city contributed $150 to the program. By 1920, a monthly allotment of $100 was allowed and the Newton Board of Education funded the school nurse position at $70 a month.

Due to a shortage in nurses in 1921, Sisters Anna and Anuta were needed at the Bethel Deaconess Hospital. From that point the Women’s Auxiliary arranged for non-Deaconess nurses to take over the position of Public Health Nurse in Harvey County.

In 1966, Sister Anna was the first Bethel Deaconess to serve for 50 years

Sister Anna Gertrude Penner “quietly departed” on February 22, 1967. She is buried in Greenwood Cemetery along with the other Bethel Deaconesses.

Sources

- “Sister Anna Gertrude Penner”, Mennonite Weekly Review Obituary March 30, 1967, p. 12.

- Deaconesses of the Bethel Deaconess Home & Hospital, “The Deaconess and Her Ministry”, Mennonite Life January 1948, p. 30-37.

- Krahn, Cornelius and Richard D. Thiessen. “Penner, Heinrich D. (1862-1933).” Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1959. Web. 22 March 2013. http://www.gameo.org/encyclopedia/contents/P466042.html.

- Krahn, Cornelius and Richard D. Thiessen. “Penner, Heinrich D. (1862-1933).” Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. 1959. Web. 22 March 2013. http://www.gameo.org/encyclopedia/contents/P466042.html.

- Myers, Lana. Newton Medical Center: Merging the Past with the Future. Newton Healthcare Corporation, Newton, Ks, 2006.

- Writers’ Program Kansas, Lamps on the Prairie: A History of Nursing in Kansas.

- Wiebe, Katie Funk. Our Lamps Were Lit: An Informal History of the Bethel Deaconess Hospital School of Nursing Mennonite Press Inc., Newton, KS, 1978.