Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

Part 2 of a 2 part Series on Black Beaver

“Turned His Face Toward Home“

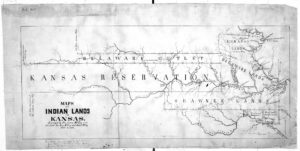

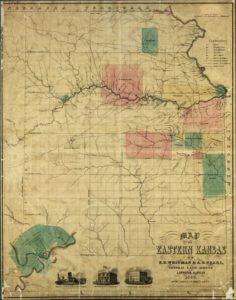

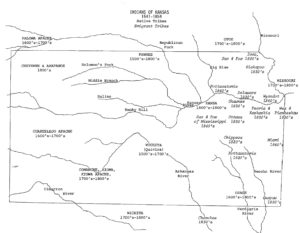

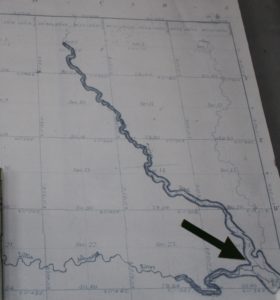

Once the garrison was safely at Ft. Leavenworth, Black Beaver retraced his route toward Washita. South of the Arkansas River, “he met his panic stricken neighbors, the people of the tribes, who were seeking safety . . . from the invasion of their own country on the Washita by Texas troops.”

They carried sad news about Black Beavers own home. What he feared had occurred,“his farm had been laid waste, his home burned and his cattle and horses confiscated and driven away.“

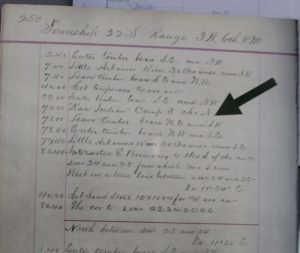

In 1862, Black Beaver wrote a letter to the commissioner of Indian Affairs describing what happened.

“In the spring of 1861 General Emery requested me to guide his command and also the combined commands from Forts Smith, Cobb and Arbuckle to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas . . I hesitated about leaving my stock until General Emery assured me that I should be paid by the United States for my losses, and on that representation I complied with his request and came with his command to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. . . When I visited my old place and found that my stock was killed some having been destroyed by the wild Indians and some by the Southern Army.” (U.S. Senate 1909, 13-14)

“What is Justly Due Him”

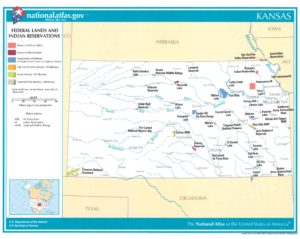

In 1872, Black Beaver filed a claim with the government for the property on the Washita River that had been destroyed by Confederates. The property was valued at $22,268. The commissioner on Indian Affairs recommended compensation of $5,000, which Black Beaver never received.

In response William G. Donna, Iowa and member of the committee on military affairs noted in his report:

“The command reached Leavenworth safety, and several officers certify to the great value of his services and his unflinching patriotism. . . . he is now over sixty years of age, too feeble to earn a livelihood and what is justly due him from the Government.”

Until his death in 1880, Black Beaver continued his efforts at securing compensation for the loss of his property while serving the United States. He never received the compensation promised to him by Col. Emory in the spring of 1861 despite being a“true friend to the army for many years.”

“Noted Delaware Leader”

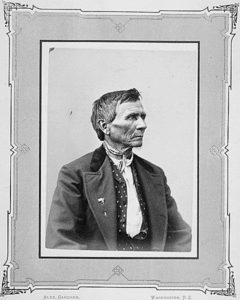

An account of Black Beaver’s life appeared in the Wichita Daily Eagle 17 September 1922. Written by Joseph B. Thoburn, Secretary Oklahoma Historical Society, the story begins “not all great Indians were chiefs or even warriors.”

Thoburn described Black Beaver’s early life as “extremely romantic,” as he traveled the “the unbroken wilderness of mountains, plain and prairie, he was schooled in the elements of resourcefulness and self reliance and became a master of the lore of all that was wild and untamed.”

Black Beaver continued to be a part of history even in his senior years. Described as a “noted Delaware leader,” he was involved with the Medicine Lodge treaty negotiations in 1867 and attended inter-tribal councils throughout the 1870s.

He had three, perhaps four, wives and four daughters. Black Beaver converted to Christianity in 1867 and became a Baptist minister. Black Beaver died May 8, 1880 at the age of 74. Initially buried near Anadarko, his remains were reinterred at Fort Sill in 1975.

Today, Black Beaver’s original grave site is listed in the National Register of Historic Places (NR 73002256).

Sources

- Thoburn, Joseph B. Secretary Oklahoma Historical Society, Wichita Daily Eagle 17 September 1922

- Ezzo, David A. & Mike Moskowitz, “Black Beaver,” 1998.

- Hauptman, Laurence M. “Black Beaver: Delaware Hero of the Civil War” American Indian. Summer 2015/ Vol 2. No. 2. at https://www.americanindianmagazine.org/story/black-beaver-delaware-hero-civil-war

- Jon D. May, “Black Beaver,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=BL001.