By Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

Click on Clark Hotel for Parts 1 & 2

“There are many lingering memories clinging about the old Clark house. . . “

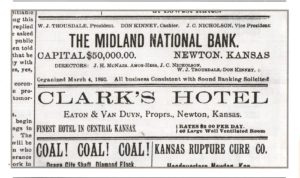

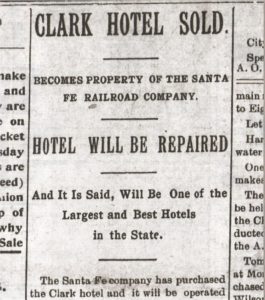

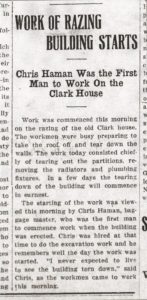

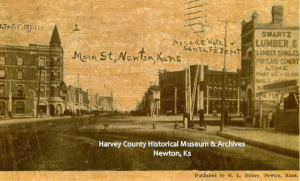

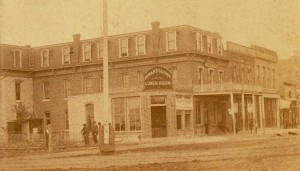

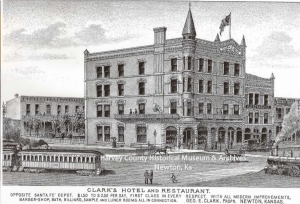

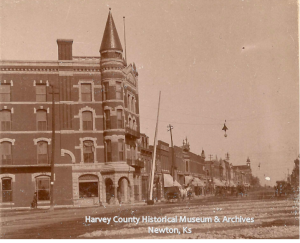

As the fate of the Clark Hotel hung in the balance in April 1913, the editor of the Evening Kansan Republican took some time to reflect on memories of one of the “finest hotels of the middle west.” In his musings, he highlighted a forgotten story from Harvey County history.

“The well-known door under the main staircase through which the thirsty traveler might follow the colored porter, or some well-posted friend, down along a long corridor, around the toilet rooms into a well-appointed bar, and there secure anything in the line of liquid refreshments – this door is still there. . . no doubt hundreds of Kansans . . . can recall many a pilgrimage through the devious windings required to secure the morning eye-opener or the parting night-cap in the old building during the period when the prohibition was gaining a stronghold in Kansas.” (Evening Kansan Republican, 19 April 1913)

Most familiar with Kansas history have heard of Carrie Nation and her saloon smashing campaign for temperance, but the story of prohibition actually begins in the 1880s and 90s. On January 1, 1881, a constitutional amendment that prohibited “the manufacture and sale of intoxicating liquors” went into effect in Kansas. For the next 36 years, Kansas worked to eliminate alcohol from the state.

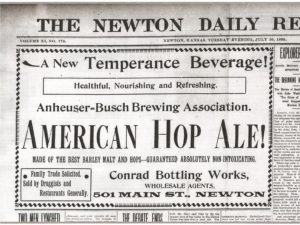

Some tried to develop “temperance drinks.”

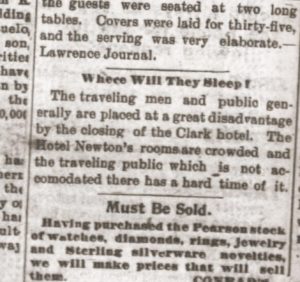

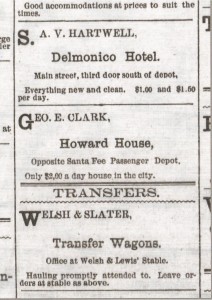

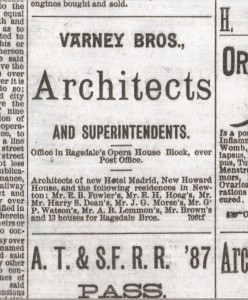

Others looked for ways to work around the new law, which was difficult to enforce. In Newton, several businessmen took advantage of the lax enforcement of the “prohibitory laws” in the late 1890s.

In the 1890s, the Newton City Council adopted resolutions to “fine the jointists of the city.” However, enforcement continued to be a problem as the editor of the Newton Daily Republican noted, “only three arrests have been made” since the resolutions. Exactly who should enforce the laws was unclear. Some blamed the county attorney for not enforcing the law and shutting down the ‘joints.’ The other side pointed out that the county attorney relied on information brought to his office for consideration. The county attorney was not a detective. Early in August 1897, Edward C. Willis complained that the “city authorities have been . . . a little slow in doing their sworn duty.” He quoted “the entire Sec. 2532, Statutes of 1889” to make his point that it was the responsibility of the sheriffs, constables, mayors, marshals, police officers “having notice or knowledge of any violations of the provisions . . . to notify the county attorney.” The tension between the two groups no doubt continued.

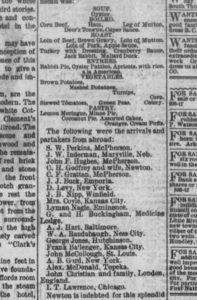

On August 26, 1897, events came to a head when Sheriff Dick Judkins, under the direction of County Attorney W.S. Allen, “moved down on the offenders, having a wagon outside to convey the spoils to the county jail for cold storage.” The Newton Daily Republican reported that four men were arrested for “violation of the prohibitory law, temporary injunctions issued upon them, and goods confiscated.”

At the Clark Hotel and a restaurant known as “Gallup’s place,” the sheriff met with some resistance. The paper reported that “at the Hotel Clark, the negro cook flatly refused to allow the sheriff to make search or look into the ice box, sitting down on top of it to prevent ingress.” The cook finally allowed the search “at the point of a revolver.”

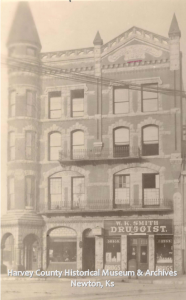

The next place searched was Conrad’s Drugstore, where “no liquor of any kind could be found.” The sheriff did however, confiscate “the icebox from the bottling works counter, with other paraphernalia.”

Judkins met with more resistance at Gallup’s when the cook again sat on the ice box, and again the sheriff’s “revolver was brought into play, with satisfactory results.” The next day, the paper retracted the stories of resistance noting that he did not know “how the story that the two cooks at the two places were so obstinate and that the revolver . . . was necessary . . . is not known. . . . Sheriff Judkins says, however, that all was peaceful.” The editor further notes that yesterday when he printed the story most people believed this to be true.

Regardless, five wagon loads of “goods” were hauled to the county jail and stored in the basement for “future disposal” as a result of the raids. Two were sent to jail, George English and Henry Gallup. The other two, E. Horan and E.E. Conrad were able to post the bond of $500 each.

A day later, more injunctions were filed against two more “druggists” and two more restaurant owners. After prohibiting the various owners from selling liquor, Probate Judge J.W. Johnson personally “went to the drug stores of E.E. Conrad, O.W. Roff, and W.D. Pearson and took away their permits to sell intoxicating liquors.” Judge Johnson noted that this was “in the best interests of the people . . . by taking away the privilege to sell liquors, which privilege had been abused grossly. . . . he meant to removed it for the good of the community.”

Sheriff Judkins was not finished, the paper reported that “immediately after arresting Mr. Porter and Mr. Roff, [Judkins] took the west bound Santa Fe No. 5 for Burrton and Halstead, where this evening he will arrest Ed Debrulier [Burrton] and . . . Charles Steininger and Carl Kaiser of Halstead. These three men are keepers of restaurants and have been violating the prohibitory law.”

The Kansas City Gazette reported the next day that “Newton Has Gone Dry” noting that ‘the joints have been running wide open in Newton for many months and until now there has been no attempt to close them.” The paper further noted that “Horan and Conrad are prominent citizens” and that “County Attorney Allen means to push the enforcement of the law and will close every place in the city.”

The Harvey County District Court convened on October 5, 1897. The docket included “the cases for the unlawful sale of intoxicating liquors.” Several went to trial, but Conrad, Horan, Porter, Roff and Pearson plead guilty to one count – “the nuisance clause.” The men paid the fines and left. County Attorney Allen cautioned that the cases were not entirely dismissed and that “the county attorney holds the whip hand and can keep the men from violating the law at any future time.”

Cases against violators of “prohibitory law” continued to appear in the newspapers throughout the early 1900s as officials sought to enforce the laws at the local level. In 1917, the “bone dry” bill, which banned alcohol statewide, was signed by the Kansas governor. Two years later in 1919, the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution made prohibition the law of the country.

Sources:

- Newton Daily Republican; 30 July 1895, 7 August 1897, 26 August 1897, 27 August 1897, 5 October 1897.

- Kansas City Gazette; 27 August 1897.

- Evening Kansan Republican; 19 April 1913.

- “Prohibition” Kansapedia- Kansas State Historical Society. kshs.org/kansapedia/prohibition/14523