by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

“There are times when patriotic Americans feel that they are losing confidence in their country’s future . . . There remains one more victory, as important and far-reaching as any – the conquering of racial prejudice.” Mabel Hillman, May 22, 1900

NHS Class of 1900

Flipping through photos of early Newton High Senior classes, I became curious when I came across the Class of 1900 photo that included one Black woman.

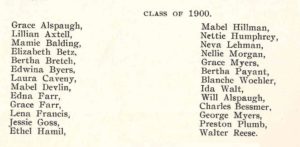

The studio photo did not come with identification other than the class of 1900. Luckily, the 1904 Mirror, perhaps the first annual for Newton High School, listed all of the graduates from 1893 to 1904.

List of names for NHS Class of 1900

The class included some well known Newton family names – Axtell, Bretch, Caveny, Plumb and Reese. Research narrowed the identity of the Black woman to Mabel or Mable Hillman.

Who was she? Could she be the first Black woman graduate of Newton High School?

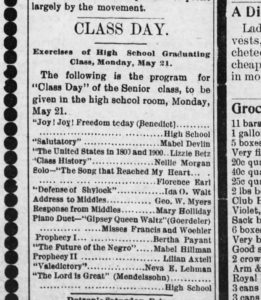

Senior Class Day

The Evening Kansan Republican, 22 May 1900 reported on “Senior Class Day,” which included “lectures instead of the usual program of orations and declamations, the graduates ‘spoke their pieces.” The room at the high school was deemed “too small” and the opera house management “donated the use of the house.”

The editor of the paper proudly proclaimed;

“There is one institution in Newton of which the citizens are proud -the high school – and as a consequence, the house was well filled at 2:15 when the curtain rose.”

The program opened with a chorus “Joy, Joy, Freedom Today,” and A. Mabel Devlin, salutatorian, extended the welcome. She then “launched into the discussion of the question, ‘Why are there so few boys in the high school?’ ” Other students followed, some with serious subjects, entertainment and music.

“One More Victory”

One of the last speakers was senior, Mabel Hillman who “spoke for her race in ‘The Future of the Negro’ treating the subject in a rational manner” according to the reporter.

Miss Hillman began:

“There are times when patriotic Americans feel that they are losing confidence in their country’s future . . . There remains one more victory, as important and far-reaching as any – the conquering of racial prejudice.”

Following the opening, she recounted the ways in which,

“the negro has played an important part in the crises of the nation. In the great wars he has been found trustworthy, brave and patriotic. . . He no longer considers himself the bone while the north and south are dogs fighting over him. But he needs the help, encouragement and guidance of the good people, and then with his own industry and skill, will he carve out his own future.”

She pointed out the many accomplishments already achieved from educational institutions, building projects and “one of the largest and finest farms in Kansas is owned by a negro.”

She closed with a story from the battle at San Juan Hill, “when the boy whose father fell at Gettysburg was by the side of the boy whose father wore the gray, and as they made that terrible charge a colored trooper crawled between them and they sacrificed in common for Liberty’s flag.”

She concluded, “in these shall he conquer. His future depends on himself, if he develop skill, intelligence and character.”

Of the speeches reported on for the article, the one given by Mabel Hillman received the most attention from the editor of the Evening Kansan Republican.

So, who was Mabel (Mable) Hillman?

There are a few clues about her life in Newton as a student and activities following graduation.

School, Church & Clubs: Mabel’s Activities

In 1896, Mabel attended Newton High school and during a Kansas Day Celebration she gave a presentation on “John Brown.”

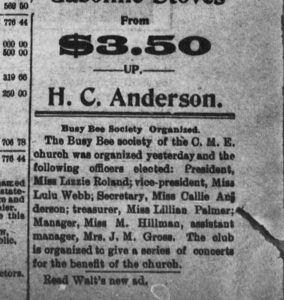

After graduation it did not take long for Mabel to find ways to be involved in her community. By the summer of 1900, Mabel, with her friend, Mrs. J. M. Gross, were “managers of the Busy Bee club.” The purpose of the club was to provide “excellent programs,” a way for Black women to gather together and a benefit for the church. The gatherings were held in homes.

During her time in Newton, Mabel was active in the C.M.E (Holsey Chapel) Church. In 1899, she with Lizzie Roland and Addie Webb gave “recitations” for the Christmas Program at the C.M.E. Church in Newton.

A benefit concert was held at the opera house for the C.M.E. Church with “an abundance of vocal and instrumental museum, interspersed with recitations and other exercises” in May 1902. Among the musical selections was a song “Every Race Has a Flag But the Coon” performed by Miss Hillman and chorus.***

A short time later the new C.M.E. Church on West 5th held a service of dedication. Miss Hillman gave the “Welcome to Our House of Worship” for the service.

N.U.G. Club

The N.U.G. Club was formed in Newton in January 1901 “as an organization among the colored people for the study of current events and the literature of the day.” In format, the club functioned much like the Ladies Reading Circle and other women’s groups popular in the early 1900s. There were 12 members the first year including Miss Mabel Hillman and Mrs. J. M. Gross.

Weekly meetings were held in the homes of members. Opening consisted of a scripture reading followed by a program. At a December 30, 1902 meeting, Mabel read one of Booker T. Washington’s addresses. There was then a general discussion on two topics: “Has the Negro as Many Friends in the North as in the South” and “Do you Think that Booker T. Washington Should Lead Us?”

February 1903, Mabel was elected president of the N.U.G. Club. During a farewell reception for Mrs. H. A. Abernathy, Miss Hillman is described as “the very worthy president.”

A brief note in a September 26, 1903 report to the Evening Kansan Republican described the most recent meeting of the N.U.G. Club with a discussion on “Home Culture”

. . . after which a dainty lunch was served, during which time, the president, Miss Mable Hillman, who will leave in a few days for California, was presented with a paper knife . . .as a token of their love and respect.”

Mabel Hillman had great concern for all aspects of the Black community in Newton. In addition to her work with women, she addressed a newly formed men’s group called the “Newton Invincibles” before she left in 1903. The purpose of the group was to work “for harmony and unity among the negroes of the city.”

In the fall of 1903, Mabel Hillman left for California. She left behind a solid foundation for the N.U.G. organization within the Black community. The N.U.G. Club continued into the 1920s as an organization.

Hillman Family

The Hillman family first appeared in the Kansas State Census for 1895 as living in Harvey County.

- John Hillman, 49, born in Kentucky, a laborer

- Cora Hillman, 47, born in Tennessee, a housekeeper

- Lulu Hilman, 21, born in Kentucky

- Mable Hillman, 17, born in Kentucky

- Jessie Hillman, 5, born in Kansas

Only Mabel is identified has having attended school.

Voter Registration records indicate that John Hillman, mid-40s to early 50s, lived at various residences, including 117 E 11th, in Newton 1888-1891. His occupation was listed as a laborer. After 1891, John Hillman does not appear in the local city directories, voter registration lists or newspapers.

In 1900, Mrs. Cora Hillman, housekeeper, age 50 is listed as living at 117 E 11th, Newton, Ks.

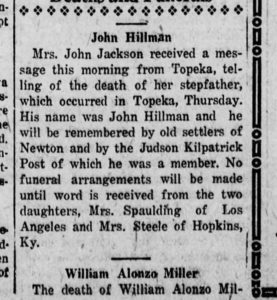

In 1922, a brief announcement appears in the Evening Newton Kansan announcing the death of Mrs. John Jackson’s stepfather, John Hillman. Mrs. Jackson’s given name was Lulu, likely Mabel’s older sister. Two other daughters are listed; Mrs. Spaulding living in Los Angeles and Mrs. Steele in Kentucky, possibly the younger two sisters, Mabel and Jesse.

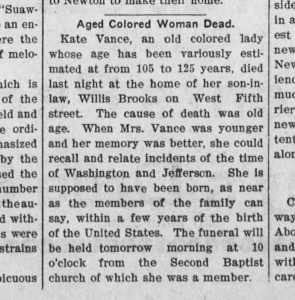

The short obituary for Mrs. Cora Ann Hillman in December 1933 notes that she was 84 years old and she passed away “at the home of her only child, a daughter, Mrs. J.J. Jackson of 119 East 12th.” No other relatives were mentioned in the notice.

Mrs. Lula (John J.) Jackson died in 1960 at the age of 87. At the time of this post, no further information on Mabel Hillman or Jesse Hillman could be found.

Notes:

**At this posting, what N.U.G. stood for has not been discovered. Contact HCHM if you know! Watch for future posts on this Harvey County organization.

***The song, “Every Race Has a Flag But the Coon” written by two white men, seems like a strange choice to perform. Even at the time it was written in 1902, it was considered offensive. Why it was sung at an African American church benefit concert is unclear.

****Was Mabel Hillman the first Black woman to graduate from Newton High School? The answer is a cautious – yes. There is always the chance that additional research will reveal an earlier graduate.

Sources

- Newton City Directories: 1885, 1887, 1901-02, 1905, 1911, 1913, 1917, 1919, 1931, 1934, 1938, 1943, 1946

- Kansas State Census, 1895

- Mirror, 1904 NHS Annual, HCHM Archives

- Voter Index Inventory, HCHM Archives

- Newton Kansan: 30 Jan 1896,

- Evening Kansan Republican: 22 December 1899, 25 December 1899, 18 May 1900, 22 May 1900, 24 May 1900, 10 July 1900, 11 August 1900, 13 September 1900, 24 December 1900, 27 February 1901, 27 March 1901, 22 April 1902, 7 May 1902, 16 May 1902, 7 June 1902, 30 August 1902, 30 December 1902, 18 February 1903, 21 March 1903, 25 March 1903, 30 March 1903, 2 September 1903, 5 December 1933, 6 December 1933.

- The Topeka Plaindealer 6 April 1900, 14 September 1906.

- “Cora Ann Hillman,” died 12/04/1933, Greenwood Cemetery, Newton, Ks.

- “Lulu Jackson,” died 11/20/1960, Greenwood Cemetery, Newton, Ks