by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

Part 2

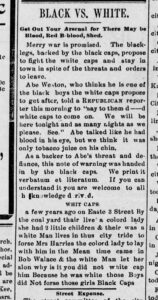

“A few years ago on Easte 3 Street by the coal yard thair live a colord lady she had 2 little children & their was a white Man lives in thus city tride to forse Mrs. Harries the colored lady to lay with him. in the Mean time came in Bob Walace & the white Man let her alone. why is it you did not white cap him? Because he was white. those Boys did Not force those girls. -Black Caps” – Abe Weston, Evening Kansan Republican, 3 April 1896.

When Abe Weston questioned why the “White Caps” had not gone after the men who had assaulted Mrs. Harris, he was not expecting the impossible. The men in the White Cap organization had imposed their own type of justice on others in the community in the past.

Who Were the White Caps?

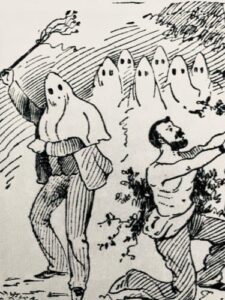

The White Caps was a group of self-appointed arbiters of community conduct, not necessarily concerned with race. They were concerned with preserving morality and maintaining social norms of the community. Both Black and white citizens were subject to their censure. The movement started in southern Indiana. It spread to other states and sometimes led to extreme violence. One of the most extreme incidents occurred in Sevier County, Tennesse where several people were murdered. In 1889, John S. Farmer described the White Caps as “a mysterious organization in Indiana” that was “trying to correct and purify society” where they felt the law was not adequately protecting citizens.

The organization’s name corresponded with its uniform. This description appeared in the Knoxville Sentinel, April 27, 1892: The White Caps scarcely ever ride horseback and wear coverings on their head similar to a hangman’s cap, also gowns or dusters reaching to, or below, their knees.

The Ominous Words ‘White Caps.’

In Harvey County, the organization was short-lived with only sporadic mentions in the newspapers over a 20-year time span, 1889-1909. The men involved were never named but at least twelve men participated.

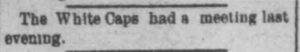

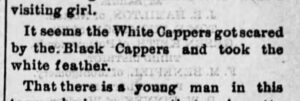

At first, the “White Caps” were viewed as something of a joke by the editor of the Evening Kansan Republican. He was often dismissive of the group. Although a meeting was noted in the Evening Kansan Republican on December 29, 1888, subtle criticisms followed.

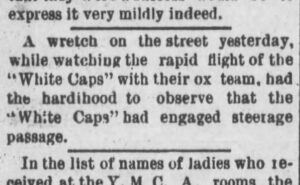

Likely, they were planning for the New Year’s Day Parade. In the next issue of the paper the description included details about the parade. The editor of the Evening Kansan Republican was not impressed with the White Caps and their contribution to the parade. He complained that “everything went along smoothly and without confusion . . . the only departure from this rule was in the case of the ‘White Caps’ who sailed around at the rate of one knot an hour in a covered wagon drawn by Frank Dickensheet’s prize oxen, and with the banners on the wagon bearing the ominous words ‘White Caps.’ (Evening Kansan Republican 2 January 1889)

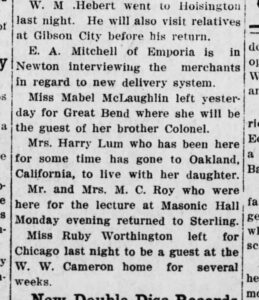

Another clipping from the paper regarding the New Year’s Day parade.

A few years later, the editor of the Weekly Kansan Republican seemed annoyed by the group when he noted in a February 6, 1898 “that ‘white cap organization’ in this city is going the rounds. It is wonderful how familiar some people are with such things.”

The men of the group were serious about their duty of monitoring the morals and social activities of the community. In 1889, John Burns, a farmer living north of Sedgwick, caught their attention.

White Caps & John Burns – 1889

By February 1889, small notices appeared in the local newspapers making threats to those the White Caps felt were acting outside of the morals of the county. In the Evening Kansan Republican on February 8, 1889, a notice appeared from the Sedgwick White Caps. They explained that they had left a notice for Mr. Burns of Sedwick which stated:

John Burns: You are hereby notified to move off of this place inside of 3 days from this date. What you get tonight will be nothing compared to what you will get if we have to come back. We will hand you to the first tree we come to. – White Caps”

This followed the typical pattern of the group. The notifications would be sent to the offender as a warning. The notices always had “a regular skull and cross bones and red ink seal.” The note also stated that Burns’ daughter who was living at the house should leave “before that night as they would call on them.” Burns’ son saw the note and for some reason did not share it with his father. He took his sister to visit a neighbor, leaving their father at home alone.

Alone in the farmhouse, Burns heard a number of men approaching. He blew out the lights and waited with an ax as his only weapon. Later he reported; “The men came close to the house and after firing a large number of shots into it with revolvers left.” They also left a second notice written in red ink; “We will give you two days to leave and if at the end of that time we come and find you here, we will hang you to the nearest tree. – White Caps”

Burns reported the incident to Deputy Sheriff Groom, who investigated at once and promised to provide protection. The editor pondered “what Mr. Burns has done to make himself offensive to the cowardly regulators.” (Evening Kansan Republican 07 February 1889)

Apparently, Burns was ready for their next visit at which they “riddled his house with bullets” but nothing more. Perhaps they were scared off because Burns “had fifteen old army comrades with him and each armed with a rifle.” Burns insisted that he would remain in his house and that he was ready for the White Caps, which the newspaper editor noted, “will no doubt make it interesting for any that come to regulate him.”

What was the motivation for the White Caps to visit John Burns?

One of the activities that the White Caps frowned on was abusive behavior. From the pension records for John Burns, it is clear that he was abusive to his wife. The abuse was so bad that she often feared for her life and lived apart from him. In April 1902, he was declared insane and sent to the Asylum in Topeka, where he died a short time later on April 26, 1902.

Walton White Caps

The youth of Walton caught the attention of the White Caps in 1892. The White Caps sent warnings to change their behavior. (Evening Kansan Republican, 16 January 1892) Nothing more could be found, presumably the young people changed their behavior.

The End of the White Caps

The group’s activities dwindled after 1896 and the incident with Abe Weston.

In 1909, there is one last mention in the Weekly Kansan. It was reported that the two men run out of town by “so-styled White Caps” had returned. The men received a second warning from the group. Nothing more was reported in the paper.

For a short time, some in Harvey County resorted to a type of vigilante justice that had echoes of past groups like the KKK and perhaps foreshadowed the revival of the Klan in the 1920s in Harvey County.

For more on Abe Weston – “Not the Most Peaceful People on Earth” Abe Weston – Harvey County Historical Society

For John Burns’ story – “A Woman of Good Moral Character” John Burns Pension – Harvey County Historical Society

Sources

- These racist vigilantes inspired the Ku Klux Klan and battled state governments for years | by Matt Reimann | Timeline | Medium

- The sad era of the White Caps | Community Columns | newportplaintalk.com

- Isaacs, Charles C. “The White Caps: A Case Study of Violent Resistance to Social and Moral Change in the United States” Indiana University Southeast, 4/26/2021

- John S. Farmer, Americanisms, Old and New: A Dictionary of Words, Phrases, and Colloquialisms

Peculiar to the United States, British America, the West Indies, Etc..,Etc.,: Their Derivation, Meaning andApplication, Together with Numerous Anecdotal, Historical, Explanatory[S.I] (London: Privately Printed by T. Poulter,1889),557.

- John S. Farmer, Americanisms, Old and New: A Dictionary of Words, Phrases, and Colloquialisms