by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

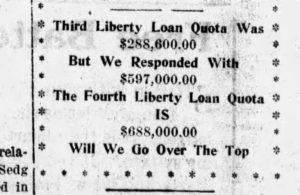

Throughout the fall of 1918, Harvey County was focused on the war effort in France. The purchase of Liberty Bonds was one way to show support for war efforts at home.

Liberty Bond Booth, Fall 1918. Intersection of 6th & Main, Newton, Ks. (Kansas State Bank in the background)

“Crowds Expected to Gather”

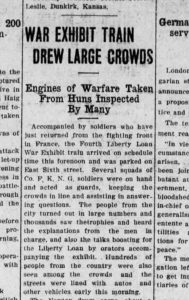

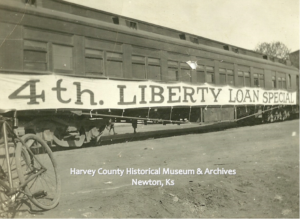

To kick off the 4th Liberty Loan Bond drive, a train with a war exhibit stopped in Newton on Saturday morning, September 28, 1918. Across the nation, kick-off events were held to encourage the purchase of Liberty Bonds. As part of the promotion, twenty-four trains traveled from town to town reaching four towns each day. On board, were “speakers and salesmen” who received “subscriptions . . . as they moved place to place.”

In the days prior to the trains arrival, the newspaper editor assured the public that there would “be ample space for the crowds expected to gather.”

“Mud of the Trenches”

On Saturday morning, the train under the guard of three squads from Co F National Guard arrived and parked at east 6th. The train consisted of two flat cars, one box car and a Pullman. Items on display were “all newly captured” at the front including German howitzers and siege guns. Together the objects “show . . . what our men are going through over at the front.” Many of the objects were captured during a battle at Hoboken on September 12, 1918 and arrived in Newton “with mud of the trenches adhering to their wheels.”

Wounded soldiers recently returned from the trenches in France also accompanied the train.

The occasion was also marked with a parade of the Newton drum corps under that direction of Paul Hubner.

After completing the tour, “the war material, guns, bombs, were returned to France “to be used in the war on the Hun.”

The editor of the Evening Kansan Republican noted:

“Perhaps no one thing could be picked out as of special interest, but it was all a display that brought the people into a feeling of closer proximity to the actual fighting.”

List of objects in the War Exhibit

4th Liberty Loan Drive

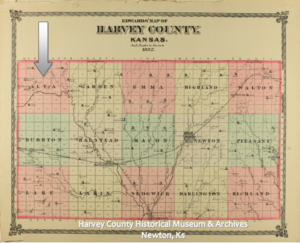

The week following was devoted to “education, publicity, and preparation.” Sunday, October 6 was declared “Liberty Loan Sunday” and subscriptions to the loan would take place October 7 through October 12. The quota for Harvey County was $688,000,000.

The following week, October 14-19, was “devoted to cleaning up unfinished work and looking after slackers.”

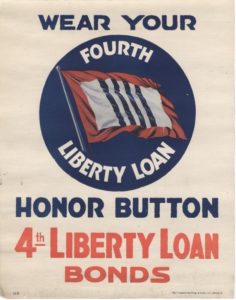

A new button was created. Earlier buttons had a metal base with a celluloid cover with a lithograph design. Buttons for the 4th Liberty Loan did not have the celluloid due to expense and “the fact that it is needed for making explosives.” The design was lithographed on the metal at nearly half the cost. More than 30,000,000 buttons were ordered.

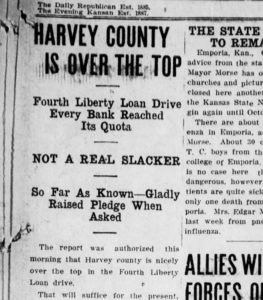

“Over the Top”

The Saturday, October 19 Evening Kansan Republican reported that “Harvey County is nicely over the top in the Fourth Liberty Loan drive.”

Click the link below to watch President Wilson leading the 4th Liberty Loan Parade in September 27, 1918 at Pennsylvania Railroad Station, New York.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rvFKmyOIQfg

Sources:

- Evening Kansan Republican, 26 September 1918, 28 September 1918, 19 October 1918.

- Newton Journal 27 September 1918.