by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

Working at a museum is never dull – you never know who will walk in the door bringing the next treasure! Recently, our neighbor across the street, Kelly Hayes, Furniture Warehouse, stopped by to give us some photos he ‘laying around.’

What a treasure!

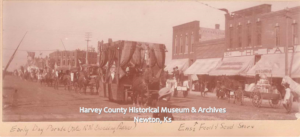

The photos match other photos we have of a street fair in 1899 – seen below.

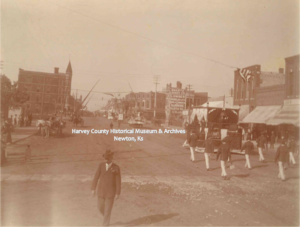

Parade, Main Street, Newton, Ks. 1899. 200 Block on the east side with the AT$SF Railroad Depot and crossing arms visible in background.

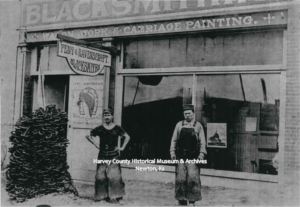

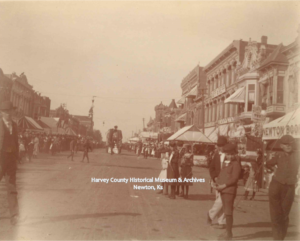

Below is on of a series of 4 photos that we have in our collection.

Photos recently donated.

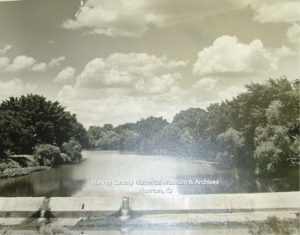

Looking north toward the railroad tracks.

The former Clark Hotel on the left, Arcade/Atchison & Santa Fe Depot on the right.

Note on dating: According to newspaper accounts and other photos in the collection, the Arcade building was remodeled with a different roof line and re-opened in May 1900. On the right hand side of the photo, east side the 400 & 300 block including Swartz Lumber at 322 Main.

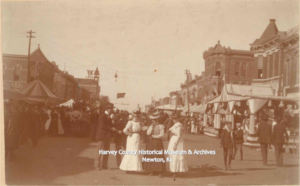

Looking north down Main, east side, 500 Block.

Duff & Duff Furniture & Undertaking, 516-518 Main. Opera House tower visible on the left hand side of photo. This block was destroyed by fire on August 4, 1914.

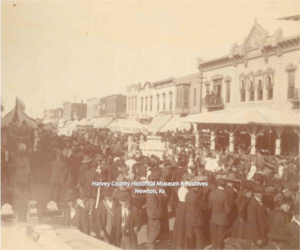

Looking north down Main, east side, 500-600 Block.

Visible on the right – Kansas State Bank; visible on the left – Opera House Tower.

Looking north down Main, east side, 600 Block.

Lehman’s Hardware & Implements, 604-608 Main.

Copies of Photos Available!

These photos may have been taken by F. H. Mann, who worked at the Kansan Book Bindery, and available for purchase.

The Book Bindery was started in March 1898 with Mann at the helm by the Evening Kansan Republican. He had learned his trade at his father’s bindery in Quincy, Ill and had worked in Topeka before Newton.

More on the Clark Hotel and here.

Sources

- The Evening Kansan Republican: 2 March 1899, 7 October 1899. 13 October 1899, 15 May 1900.