Traces of the past are all around us . . . and sometimes right under our feet. Guest blogger Michael Wingo relates how his father, Gene and others, dug up a piece of Harvey County history in 1966.

by Michael Wingo

It was late October of 1966 and the men of Rhoades Construction’s sewer projects crew were looking forward to the coming winter and the seasonal shut-down of operations. They could rest and enjoy the holidays and have some well-earned down-time. They were deep in the middle of a project trenching and building sewer lines for a new sub-division of Newton, Kansas.

The job was one often required when towns access new sections to add to housing areas: Trench and lay the sewer system, and place corresponding manhole accesses every few hundred feet. A massive bucket-fed trenching machine was used to dig the long straight lines the pipelines would follow. At strategic places along the lines, access holes would be constructed to use for maintenance, cleaning and so forth. These are known as manholes, areas that are enclosed with a lid that can be removed from the top allowing access to the pipeline.

The crew that day included my father, Gene Wingo, who was the grade man in charge of making sure the pipe was all placed at the proper level and depth, and in the correct orientation. Herb Keazer, job foreman (now deceased), was operating the large trenching machine. Additionally, Harrold Berg (now deceased) and Jim Rosiere were assisting that late October day.

At times, the job moved forward at a snail’s pace due to the saturation of ground water that was found at lower depths of the project’s required trenches. Periodically, another crew would be required to bore a deep well, and to insert electric pumps to remove the water.

As the trencher moved along, leaving behind a windrow of freshly churned earth, the men noticed a spot where the top of the pile was covered in a ground, white substance; but, time being key and wanting to move forward, they did not investigate.

Roughly a hundred feet later, the massive trencher began to cough up more white earth. As it churned, it began laboring more forcefully and then ground to a halt. The men working were somewhat shocked. The machine in question was a massive unit and was cutting a three-foot wide swath at the time. It was laboring at a depth of roughly twenty feet. What could have happened?

As they clambered around the trench for a better look, it became obvious they had trenched right into something massive across their path. First guess was a downed tree or perhaps a massive hedge post. The only thing that appeared odd was the white color of the piece. The depth was also problematic. At nearly twenty feet down, another guess was an old water-line or pipe of some kind. However, the object was not man-made, and seemed made of a white substance, similar to wood. It projected from the south wall of the ditch. The object was boarded over with a sheet of plywood similar to the shorings down the length of the ditch, and work progressed. The sewer line was put in place and over-filled with gravel.

My father then asked permission to go back, remove the plywood covering and remove the curious item that had slowed them earlier. He was given permission to cut the shoring and dig into the side of the ditch, a somewhat dangerous task given the amount of moisture and depth of the ditch. Jim Rosiere helped and, with shovels, they began trying to remove the odd object. They had to work quickly and carefully to avoid the collapse of the trench wall.

The men cut back roughly eight feet, with their quarry never seeming to end. Finally the decision was made to take the portion uncovered. The side angle cut into the trench was becoming overly extended and dangerous. Hooking on with a cinch cable and crane, the object was lifted slowly from the trench. It was curved slightly, roughly ten feet long, and in diameter exceeded eight inches.

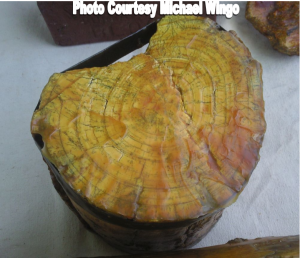

As the object was lowered to the ground, some suggested it was just an old hedge post or perhaps a petrified tree. My father decided to use a tree saw and slice some sections off to give to the men who had helped. He cut a few large sections off, dulling several saws. Harrold Berg, Herb Keazer, and Jim Rosiere were given pieces. The remainder was left to my father. The object was clearly white and had rings similar to a tree. The men were baffled what they had found. My father’s large piece was taken to a local rock-and-mineral-club member, my grandfather Raymond Wingo. He began to examine the piece and work with it a bit.

The following morning, my grandfather visited my father and told him–quite excitedly–that the strange object was ivory!!! The crew had stumbled upon a prehistoric mastodon tusk! The level it was found in was composed of soft dirt with groundwater present constantly, so the entire tusk was saturated with water. As it dried, it became obvious that it would be at risk to crumble or deteriorate. The decision was made to coat the pieces with wax or tung oil to protect it from exposure.

As my grandfather was a member of the Newton area gem and mineral society, the site was closed for a day to allow the local townspeople, teachers, and curiosity seekers to come see what had been found and from where it was removed. The trench area was lined with boards to walk on and curious people came to look and see.

The foreman of the job announced they had found nothing except a dumb old hedge post and ordered the crew back to work the following day. Roughly a week later, as they were digging a manhole some 300 yards east and north of the previous location, my father spied, along the edge of the freshly dug soil, the glimmering edge of another tusk. He kept his secret and waited.

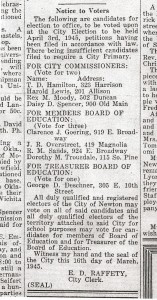

Newton Kansan, 1966. Mastodon Tusk held by Jim Rosiere (lt) and Gene Wingo (rt). HCHM Photo #2012.166.10

Another week and the job site was closed down for the Christmas season and holidays. The very next day, close to Christmas, my grandfather and father went to the site and located the tusk, still buried along the edge of the ditch. It was located less than five feet down and was riddled with roots from the alfalfa field growing there. Snow was falling and it was freezing, but the two men kept at their task. As they had the tusk almost cleared from its shallow grave, it chose to fragment, perhaps due to the cold air. My father was heartbroken but my grandfather told him, “Go ahead and take it. You still have the pieces and can display it.”

When I was fifteen, my father gifted me with the smaller complete tusk they had removed that last day. I kept it until my grandfather passed away, at which point my father asked me if he might have it. He wished he had kept it, due to his memory of his father. I chose to return it, and was given a beautiful sphere in trade.

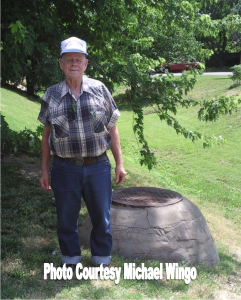

I recently spent a day with my father, jiggling his memory of the finds, and taking some pictures. He is the only crew member still alive today, except Jim Rosiere (whereabouts unknown). We walked the path the job site took, and located the general area of the two finds. That area was directly to the south of where Newton High school stands today. When the work project was ongoing, the entire area was a big empty field. Now there is a housing development, church, and all the increments of modern society located in the area. Much has changed in the 46 years since the tusks were found that cold week in late October of 1966.