by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

Based on research notes from Brian Stucky’s Alta Mill research.

“Alta was named in memory of the deceased daughter of the writer, Alta O. Muse.” — Judge R.W.P. Muse, History of Harvey County: 1871-1881.

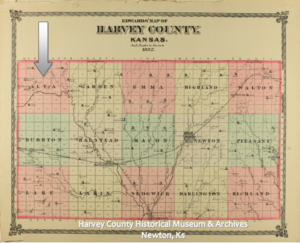

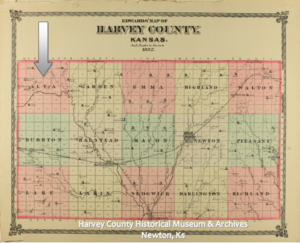

Historical Atlas of Harvey County – Alta Township indicated.

In his 1881 History of Harvey County Judge Muse, noted in the section on naming cities and townships: “Alta was named in memory of the deceased daughter of the writer, Alta O. Muse.” Alta Muse was something of a mystery to Harvey County historians. She does not show up on Harvey County census, nor was she buried in a Harvey County cemetery . . . until recently.

Brian Stucky was able to connect the name with story of Alta Muse. While researching the Alta Mill located in the Alta township in Harvey County, Stucky stumbled on a clue that led to a sad story.

This is one of those moments in historical research that you just gasp and shake, when you say to yourself, “I found her. I finally found her.” –Brian Stucky, June 2018

Stucky noted: “I always thought for some reason that Alta was a young daughter, maybe 9 years old, but I don’t know where I got that. No, she was older, age 23, and she was married to a Josiah Sinclair for almost 2 years. So, we’re looking for someone named Alta Sinclair.” Newpapers had been added to the site Newspapers.com and out of curiosity, he included a search on Alta Muse.

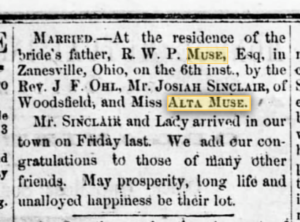

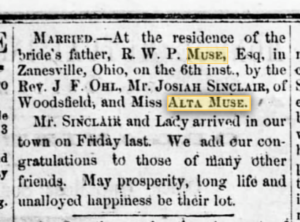

“What popped up was a newspaper from Woodsfield, Ohio, called “Spirit of Democracy.” The date of the story was April 27, 1869. Wow. And, it was the WEDDING OF ALTA O. MUSE and Josiah Sinclair, in Zanesville, OH where they lived. She was married April 6, 1869. I quit breathing for a minute or two.”

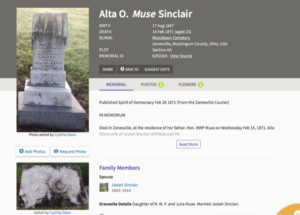

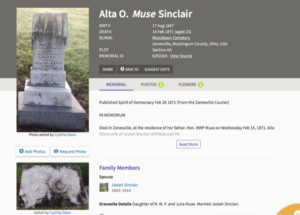

With the knowledge of her married name, Stucky searched Find-a-Grave for “Alta Sinclair.”

“And there it is, a page on her grave, picture of the gravestone, name of her father, Judge R.W.P. Muse, to absolutely confirm it.”

Who was Alta Muse?

Alta Olivia Muse was born in McConnelsville August 17, 1847 to Judge RWP and Julia Hurd Muse. She would be one of four daughters born to the couple. In 1852, Judge Muse moved his family to Zanesville, OH. On August 24, 1860, Alta’s older sister, Ada, died at the age of 19.

Alta spent her growing up years in Zanesville community, graduating from high school in 1866. She “enjoyed, in an uncommon degree, the respect and esteem of her fellow pupils and teachers, who alike recognized her moral and intellectual excellence.”

For her obituary a former high school principal praised her scholarship and character.

“Her manners and address were such as to engage in advance all opinions in her favor. Her light- hearted gayety (sic) and energy in bearing her part in every school enterprise rendering her a pleasing companion and valued associate. . . . Her application to her studies . . . established her reputation as a successful student. By the side of her early grave the writer can only remember her unusual personal attractions and agreeable manners.”

She was baptized on February 7, 1869 and as a member of the Protestant Episcopal Church, she had a strong “desire for Christian usefulness.” Many of her friends could “recall more than one incident . . . which strikingly exemplified the thoroughly practical character of her religion.“

She married married Josiah Sinclair “at the residence of the bride’s father, R.W.P. Muse” on April 6, 1869. Following the ceremony, the newlyweds lived in Pittsburgh.

Marriage Announcement, Spirit of Democracy. Woodsfield, OH, 27 April 1869.

Sadly, the couple did not have “long life and unalloyed happiness.” After “a few months, her failing health rendered it advisable that she should return to her father’s house.”

Alta died at her father’s home on February 15, 1871 at the age of 23 after a “long and tedious illness.”

A Father’s Grief

Shortly after her death in February, Judge Muse was traveling in Kansas to the new town of Newton.

Muse writes in The Harvey County History:

“The first passenger train crossed the new bridge over the Cottonwood (river) and entered Florence on May 8th, 1871. This was then the terminus of the railroad. The writer was on that train, en route for Newton, for the purpose of there erecting an office to be ready to put the railroad lands upon the market, as soon as the railroad reached that point, and was accepted by the governor.

……We arrived on the town site on the afternoon of May 10th, 1871, and passed over it to the banks of the Sand Creek, where several railroad officials had camped for the night, being on their way west to kill buffalo. We stayed that night with the late Capt. John Sebastian, who was living on a tent, on the west bank of the Sand Creek, near the end of the present Broadway bridge.”

Brian notes:

“So, Alta died Feb. 15, and by May 10, her father was camping on the west bank of the Sand Creek. No wonder the memory of his daughter was fresh in his mind. Of course it was natural for him to want to name something after Alta. It was a township.”

Alta’s husband, Josiah Sinclair, according to information on Find-a-Grave, went back Wheeling, West Virginia. He married again in 1874 and served 7 terms in the West Virginia legislature. Sinclair died in 1914.

Thank you to Brian Stucky for sharing his research notes on Alta Muse Sinclair.

For more info Lost Harvey County

Additional Sources:

- Bowman, Mrs. C.S. “Organization of Harvey County” typed manuscript, October 7, 1907, HCHM Archives, Newton, Ks.

- Muse, Judge RWP. History of Harvey County: 1871-1881.

- “Judge Muse Dead” Newton Daily Republican, 23 November 1896.

- Julia Hurd Muse Obituary, Newton Kansan, 30 July 1890

- Marriage Announcement, Spirit of Democracy. Woodsfield, OH, 27 April 1869.

- “Alta O. Muse Sinclair Obituary” Spirit of Democracy 28 February 1871, Zanesville Courier.

- Find-A-Grave, “Alta O. Muse Sinclair” Memorial Number 6292265.

- Find-A-Grave, “Josiah Sinclair” Memorial Number 187771766.

- Find-A-Grave, “Ada Burke Muse” Memorial Number 6292263.

- U.S. Census, 1850, 1880.

- Kansas State Census, 1895.