by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

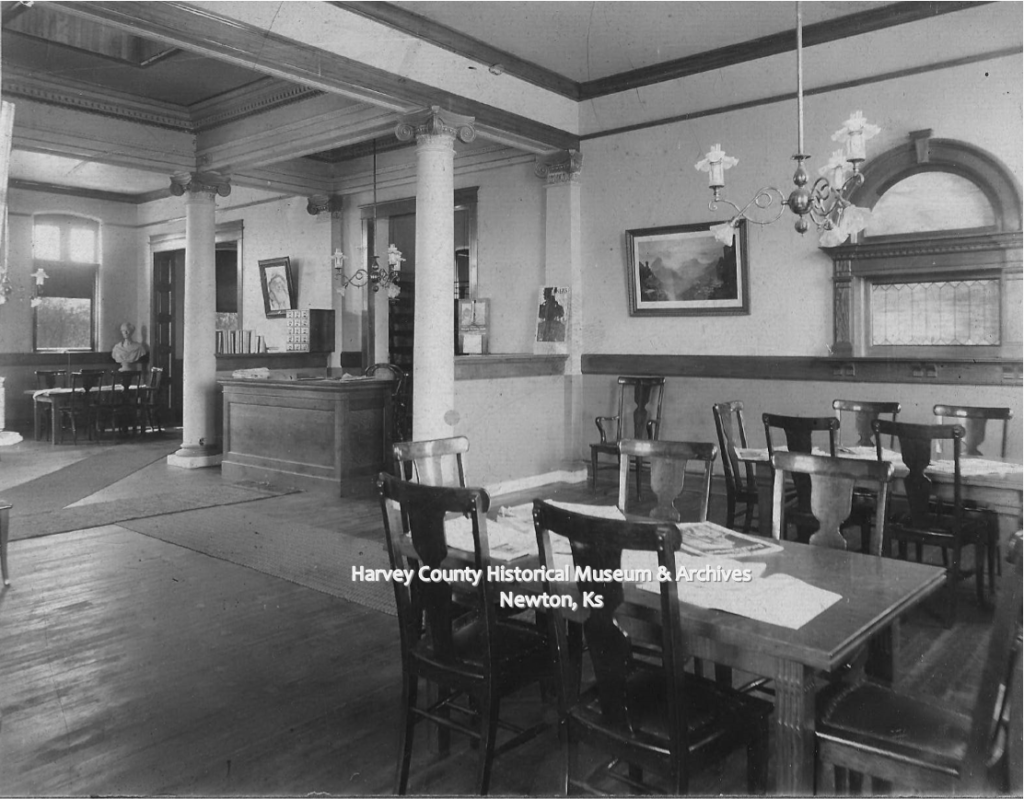

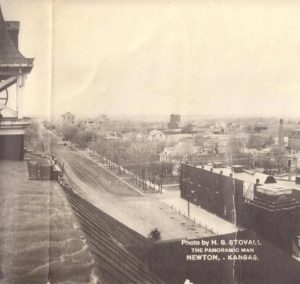

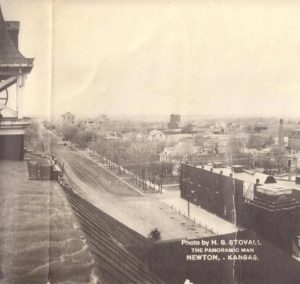

View of Newton, Ks from the roof of the Opera House, taken by H.S. Stovall.

“Photography is history and in a book like the Semi-Centennial edition of the Kansan, the the contribution of this profession to its success is obvious.” -Editors of the 50th Anniversary Edition of the Kansan, 22 August 1922.

Harvey County was fortunate to be home to several talented photographers that documented the progress of county communities through photographs. From the earliest photo taken in the summer of 1871 to today, HCHM has an extensive collection of images created by Harvey County photographers.

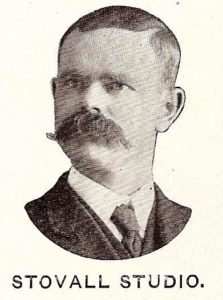

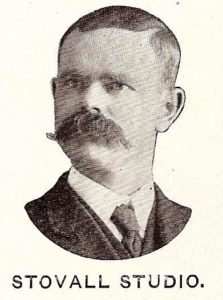

H. S. Stovall was one of several photographers active in the county in the early 1900s. Born in Kentucky in 1872, Stovall moved with his parents to Missouri. He attended the Chillicothe Normal School and Business Institute located in Chillicothe, Mo. While studying business at the college, Stovall became interested in photography. After he graduated, he “devoted his entire business energy to this profession.”

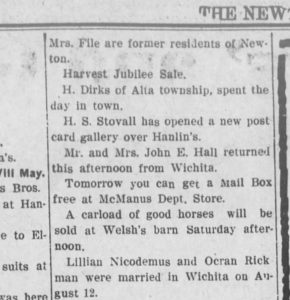

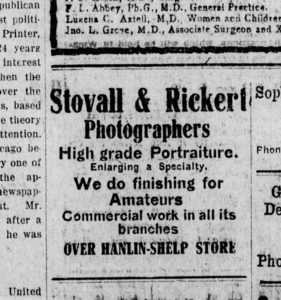

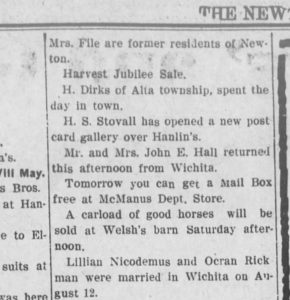

Evening Kansan Republican, 9 September 1909.

By 1909, this “progressive business man” had moved to Harvey County where he was “an earnest worker for the best interests of Newton.”

H. S. Stovall

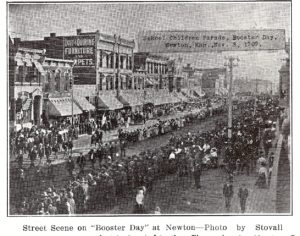

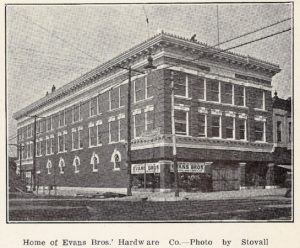

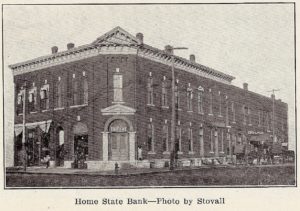

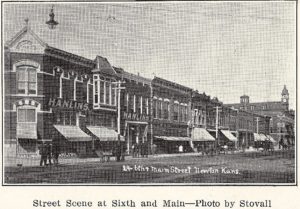

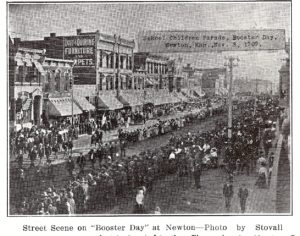

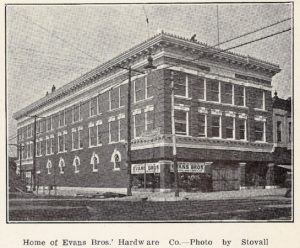

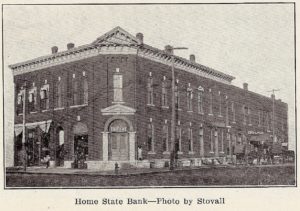

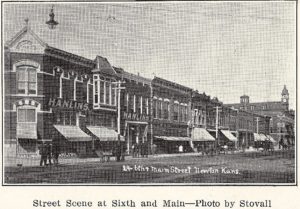

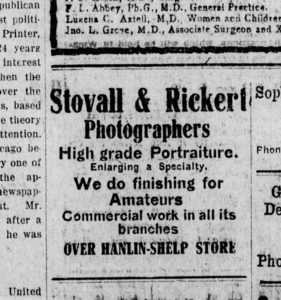

He opened a gallery above Hanlin’s Department Store at 603 Main in Newton, Ks. Stovall provided many of the images for the 1911 Souvenir publication “Newton, Ks: Past & Present, Progress & Prosperity.”

Panorama Photography

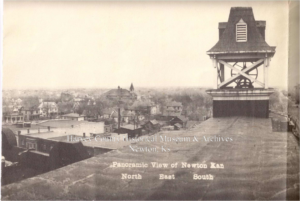

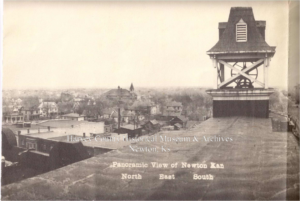

One focus of his work was on creating panoramas including one taken pre-1915 from the roof of the Opera House.

View of Newton, Ks from the roof of the Opera House, taken by H.S. Stovall.

Enlargements

Enlargement looking east.

Enlargement looking north.

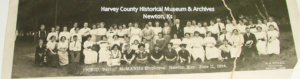

Large Groups Photos

He also was a popular photographer when the subject was a large group.

District Meeting. Church of the Brethren, 1015 Oak Newton, Ks. 1911 taken by H.S. Stovall.

McMannus Employee Picnic, June 11, 1914, Photo by Stovall.

1st Christian Church, Main & E 1st, Newton, 1918. Photo by Stovall.

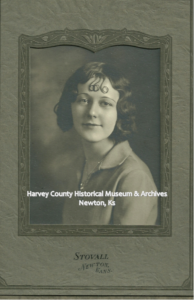

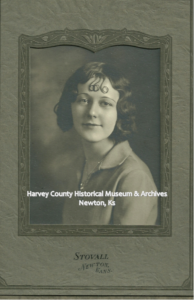

Senior Photos

Florence Holmes, 1928.

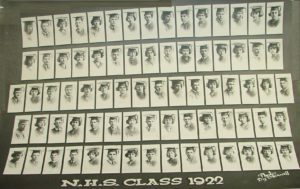

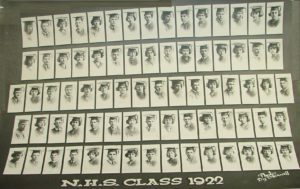

NHS Class of 1922, by Stovall.

Portraits

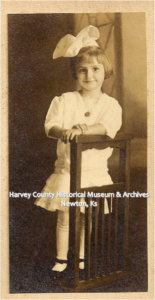

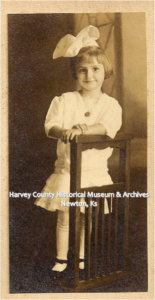

Janet Parris, 4 years old, 1916. Photo by Stovall.

Evening Kansan Republican, 19 August 1914.

In 1924, Stovall is listed on Socialist Ticket Presidential Electors, along with Reed Crandall from Newton, Ks.

Council Grove Republican, 24 July 1924.

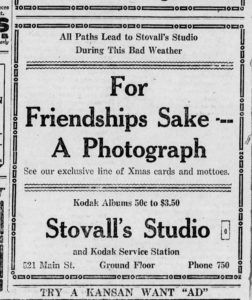

He was an active photographer in the Newton community throughout the 1920s.

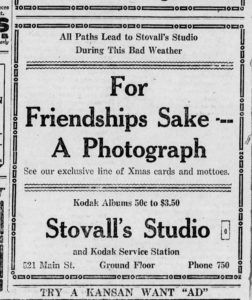

Evening Kansan Republican, 10 December 1920.

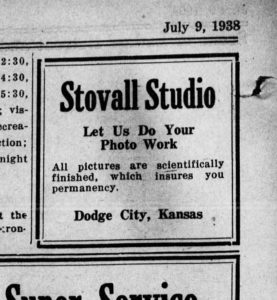

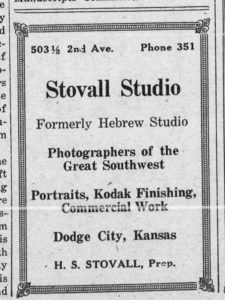

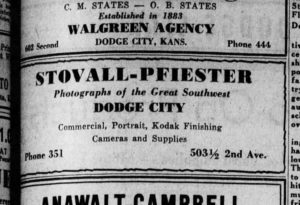

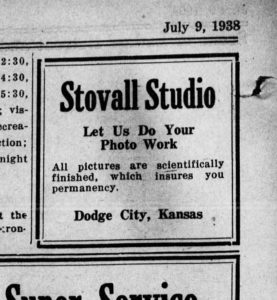

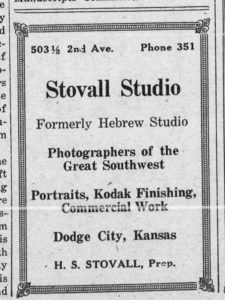

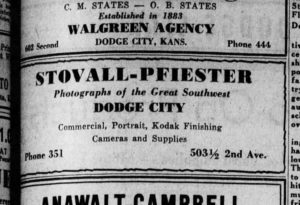

By the 1930s he is advertising in Dodge City, Kansas newspapers and the Catholic Advance.

The Independent, 9 July 1938.

Catholic Advance,9 February 1935.

The last advertisement that was found for this article was in the Catholic Advance January 16, 1942. Stovall would have been about 70 years old.

Catholic Advance, 16 January 1942.

If you have information on H.S. Stovall, contact HCHM.

Other Harvey County Photographers

Charles L. Gillingham, W.E. Langan, F.D. Tripp, W.R. Murphy, Mrs. B.F. Denton.

Sources:

- Catholic Advance: 1 October 1929, 2 February 1931, 9 February 1935, 9 July 1938, 16 January 1942.

- Council Grove Republican, 24 July 1924.

- Evening Kansan Republican: 9 March 1909, 20 April 1909, 7 September 1909, 9 September 1909, 8 September 1910, 13 February 1913, 6 March 1913, 19 August 1914, 5 September 1914, 8 March 1916, 17 April 1917, 8 September 1917, 30 September 1918, 10 May 1920, 17 September 1920, 21 September 1920, 30 September 1920, 20 October 1920, 23 October 1920, 10 December 1920, 22 August 1922,1 September 1920.

- The Independent: 27 July 1922, 2 November 1922.

- Newton City Directories: 1911, 1913, 1917, 1919, 1931, 1934, 1938.

- United States Census: 1900, 1910.

- Kansas State Census: 1915.