Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

One of the largest collections in the archives is the the John C. Johnston Collection of Civil War Pensions. The collection consists of 287 files from Harvey County families that applied for pensions through claim attorney John C. Johnston. Johnston himself was a Civil War veteran whose injuries included a “shell wound of the face.”

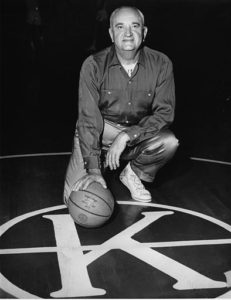

John C. Johnston, Newton attorney, ca. 1930.

Each claim has a file folder with information about the man and his family.

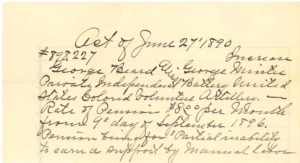

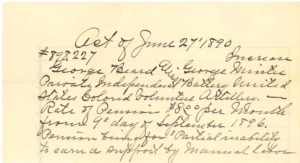

Disability Act of 1890

On 27 June 1890, Congress passed the Disability Act of 1890. This Act extended pension benefits to veterans who could prove at least 90 days of service in the Civil War (with honorable discharge) and a disability not caused by “vicious habits,” even if unrelated to the war. Perhaps even more important, the Act provided pensions to widows and dependents of deceased veterans, even if the cause of death was unrelated to the war.

George Beard Folder, John C. Johnston Civil War Pensions Collection.

The file for George Beard is seemingly simple, but a closer look revealed Beard was part of a unique unit in the Union army – the Independent Battery U.S. Colored Light Artillery and his descendants continue to live in Harvey County, Ks.

On August 15, 1864, under the alias of George Winter, Beard enlisted as a a private in the Independent Battery U.S. Colored Light Artillery. He served until July 22, 1865 in the “war of the rebellion” when he was honorably discharged.

“Douglas’s Battery:” the Independent Battery U.S. Colored Light Artillery

Independent Battery, U.S. Colored Light Artillery, Ft Leavenworth, Ks, 1864

The Independent Battery U.S. Colored Light Artillery had the distinction of being the only federal unit to have the leadership made up entirely of Black officers. Commonly known as Douglas’s Battery in honor of Capt. H. Ford Douglas, the commanding officer was William D. Matthews (pictured below).

William D. Matthews, the commanding officer.

Matthews recruited from Fort Scott, Wyandotte and Quindara communities. Of the recruits, more than one third were teenagers as young as 17. Most were born in slave states including Missouri, Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee. As former slaves, most were illiterate.

George Beard: “A Colored Man of Strong City”

George Beard, alias George Winter, was born in Tennessee in approximately 1846. At the age of 18, he enlisted in the newly created Battery at Ft Leavenworth, Kansas. After George was honorably discharged at he returned to Kansas and settled in Strong City, Kansas.

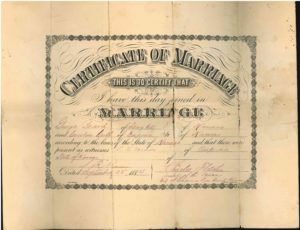

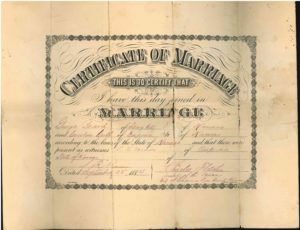

He married Caroline Cobb of Emporia, Ks on September, 22, 1884. George is listed as living in Strong City on the marriage certificate.

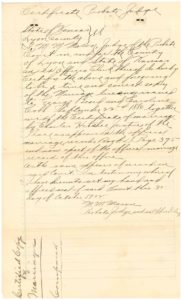

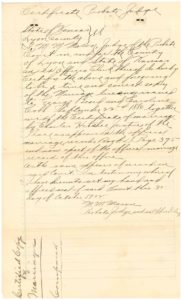

Marriage Certificate, 1884. Civil War Pensions, George Beard Folder

His wife, Caroline Cobb Beard, died December 9, 1890. The couple had one son, William H., and possibly a daughter, Florence.

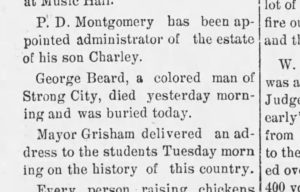

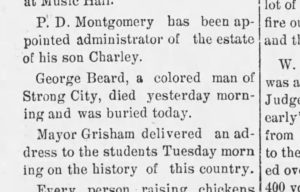

In January 1902, a brief notice appeared in the News Courant, a Chase County newspaper:

“George Beard, a colored man of Strong City died yesterday morning and was buried today. “

News Courant, 19 June 1902.

The Minor Child of George Beard, alias George Winter

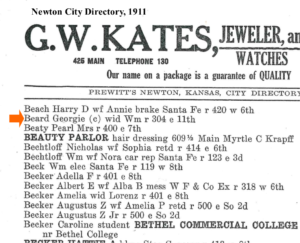

When George died in 1902, William or “Willie” was already living with an aunt, Belle Ramsey, in Newton, Ks. For unknown reasons, the children lived at the home of Belle and C.R. Ramsey in Newton. The Census of 1900 listed both Florence Beard (15 niece ) and Willie Beard (12 nephew) living in the household of C.R. and Belle Ramsey.

George had been receiving a pension of $8.00 per month since September 9, 1896 for “partial inability to earn a support by manual labor.” According to the 1890 Act, his minor children were eligible for this money.

Belle Ramsey became the guardian of the minor child, Willie and applied for the pension. In order for her to get the pension, she had to prove that George and Caroline were married and that William was a legitimate son. Local attorney John C. Johnston helped her with this project. The marriage certificate was of great importance. Additional documentation from Lyon County also was requested to confirm the marriage.

Civil War Pensions, George Beard Folder

Beard-Thaw Family

William “Willie” H. Beard died of tuberculosis on April 7, 1910. He was living at the home of C.R. Ramsey and was survived by his wife of about a year, Georgia White Beard. He was only 23 years old.

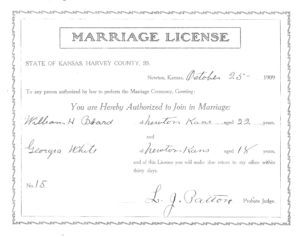

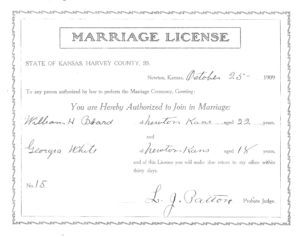

Marriage License – William H. Beard and Georgia White, October 25, 1909.

A son, William H. Beard was born roughly a month later to Georgia Beard.

Georgia White Beard Thaw continued to live in Newton, Ks. She died 1979 at the age of 88.

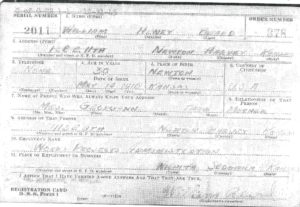

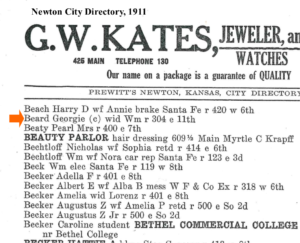

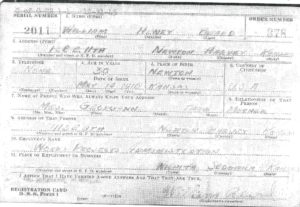

William H. Beard’s draft registration card shows that he worked for the Works Projects Administration.

Selective Service Draft Card.

After the war, married Esther Pitts and worked for the City of Newton. He died in July 1983.

Sources

- John C. Johnston Collection of Civil War Pensions, George Beard Folder. HCHM Archives, Newton, Ks.

- Evening Kansan Republican, 7 April 1910 (death notice for William H. Beard), 7 December 1925.

- Newton Kansan: 28 July 1983.

- News Courant, Cottonwood Falls, Chase County 19 June 1902 (death notice for George Beard).

- Marriage License Collection, HCHM Archives, Newton, Ks

- U. S. Census: 1900, 1910, 1930

- Kansas State Census: 1915.

- WWII Draft Registration Cards for Kansas 1940-1947.

- Newton City Directories; 1909-10, 1911, 1920, 1923-24, 1926-27, 1930-31, 1940, 1952, 1960.

- Cunningham, Roger D. “Douglas’s Battery at Fort Leavenworth: the Issue of Black Officers During the Civil War” Kansas History p. 201-217.