by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

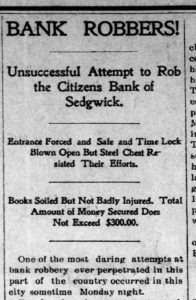

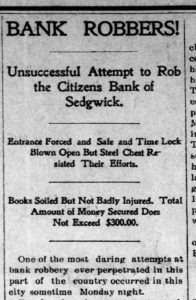

“One of the most daring attempts at bank robbery ever perpetrated in this part of the country occurred in this city sometime Monday night.” (Sedgwick Pantagraph, 23 January 1902.)

Sedgwick Pantagraph, 23 January 1902.

“Daring Attempt”

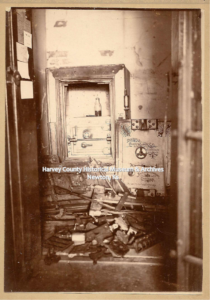

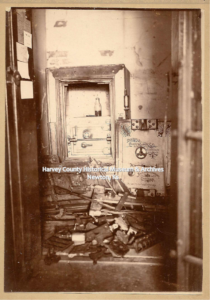

According to the news reports, the burglars “forced an entrance through the west window . . . picked a hole through the thick walls of the vault” at the Citizens Bank of Sedgwick January 22, 1902. They continued and “knocked off the combination lock” and made their way through the outer door. To get past the time lock and “heavy steel doors,” they employed nitroglycerine and blew it up.

Past that hurdle, they were unable to get to the “compact little steel compartment which was protected by a combination lock” open. They gave up after damaging the smaller vault with a hammer. This vault had over $6,000. For their efforts “all the booty . . . they secured was the loose silver in the counter tray . . . and a Colts revolver from the drawer at the cashier’s window.” The estimated value of what was taken was $100.

Prior to breaking into the bank, the “robbers broke open the Santa Fe tool house and secured a pick, hammer crowbar and other tools to crack the safe.”

The Heart of Town

Initial reports noted that despite being “committed in the heart of the town” the burglary was not discovered until 7 o’clock Tuesday morning. The broken window was noticed by “Post Master Mueller’s boy.” Some reported hearing explosions earlier, but “they were so muffled that little attention was paid.”

Later reports, note that the night watchman discovered the break in around 4 a.m.

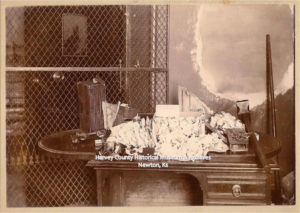

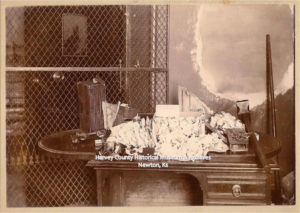

When Mr. Anderson arrived and opened the bank “the wreck disclosed was something frightful. Books, papers, brick and mortar were scattered everywhere, and the big heavy steel doors of the vault were torn and twisted.”

The Escape

In the rush to get away “the tools were left where they were dropped by the burglars after they decided to abandon their project. . . they stole a hand car and went south over the Santa Fe toward Wichita.”

The robbers were spotted at 4 o’clock in the morning by a man living near Wichita Heights. He was awakened as the handcar passed by and saw the robbers at a distance. At the time he did not know of the Sedgwick robbery.

The burglars abandoned the handcar at Valley Center “evidently the work of propelling it was too hard” where it was found Wednesday morning. (Topeka Daily Herald, 22 January 1902)

Area papers reported the news across the state.

“At about two o’clock yesterday morning burglars robbed the Citizens” Savings bank here of a box of silver containing $100. The burglars dug through the brick walls of the vault and then blew off the door of the safe with dynamite. In their haste they missed the bulk of the money but escaped with what little they secured.“

Perhaps in response to the January burglary, the Sedgwick State Bank announced on February 27 that they were “fitted out with an up-to-date electric burglar alarm . . . now better protected against daylight holdups and night burglaries” (Sedgwick Pantagraph, 27 February 1902.)

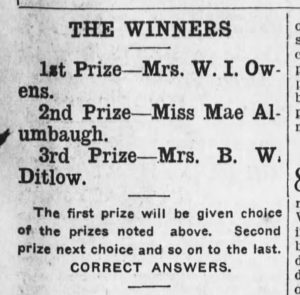

“Identity of the Robbers“

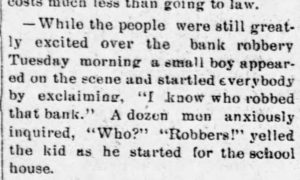

Despite being amateurs, it is unclear if the culprits were ever found. The Pantagraph reported that “no clew (sic) has been obtained as to the identity of the robbers.”

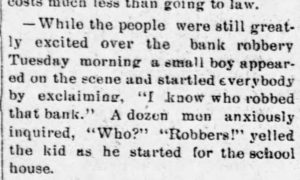

Although one clever boy claimed to know, and the paper reported his theory.

“A small boy appeared on the scene and startled everybody by exclaiming, “I know who robbed that bank.”

A dozen men anxiously inquired, “Who?”

“Robbers!” yelled the kid as he started for the schoolhouse.

Sedgwick Pantagraph, 23 January 1902

At the time of publishing this post, research has not revealed if the burglars were ever caught or sent to jail.

Sources

- Sedgwick Pantagraph: 23 January 1902, 27 February 1902.

- Topeka Daily Herald: 22 January 1902