by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

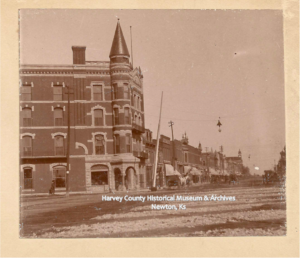

On November 7, the people of Harvey County will have the opportunity to vote on several local issues of importance. Today, candidates use a variety of methods to get their message out to the voters. Social media, including twitter and Facebook, can have a huge impact on results, both locally and at the national levels. The influence of television was experienced in 1960 and the first live Presidential debates between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon. Where people today rely on TV and social media for information in past years, local newspapers have been an important avenue for candidates. The race for Harvey County sheriff in 1908 could be one example.

“An enviable record as a soldier, and his bravery, . . . is unquestioned.”

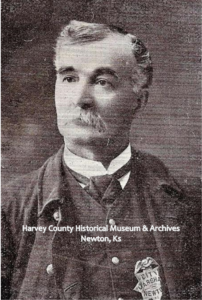

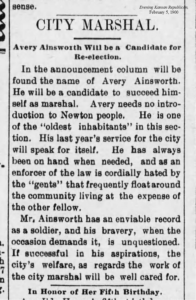

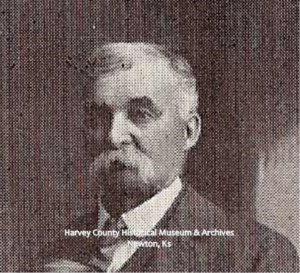

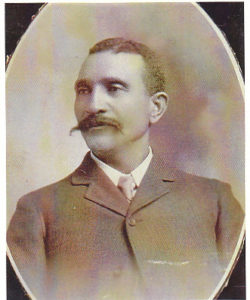

Avery R. Ainsworth was a respected member of the Newton community. He served as City Marshall in the early 1900s. In the bid for re-election in 1900, the editor of the Evening Kansan Republican noted:

Ainsworth “has always been on hand when needed, and as a enforcer of the law is cordially hated by the ‘gents’ that frequently float around the community living at the expense of the other fellow. . . he has an enviable record as a soldier, and his bravery . . is unquestioned.”

While serving as City Marshall, he assisted the County Sheriff on raids “made on ‘refreshment stands'” or “joints” to enforce prohibition.

He also served on the Board of Education for the Newton schools in 1904.

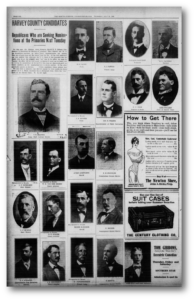

Harvey County Candidates in 1908.

In 1908, Ainsworth announced his candidacy for sheriff on the Republican ticket. In the republican primary he faced W.E. Johnston, “one of the staunch and true republicans of Highland township.” In the August primary, Ainsworth prevailed to get the republican nomination for sheriff.

The Evening Kansan Republican urged party unity. In the section titled “Comments Wise and Otherwise,” the editor S.R. Peters noted;

“If he [a voter] takes part in the primary he is honor bound to stand by the ticket nominated by the system, regardless of his personal feelings or bias.”

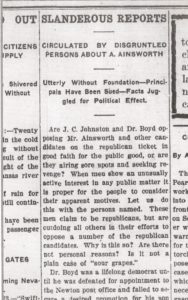

In the fall of 1908, rumors and controversy swirled around Ainsworth and in October, editor Peters, sought to answer the critics.

Good Faith for Public Good?

He posed these questions:

“Are J.C. Johnston and Dr. Boyd opposing Mr. Ainsworth and other candidates on the republican ticket in good faith for the public good, or are they airing sore spots and seeking revenge?or airing sore spots and seeking revenge?”

Using more than a full page of newsprint, Peters carefully reviews the facts as he knew them in defense of A.R. Ainsworth and the “republican ticket.” He noted that it was important in this case to name the people involved to understand the motives.

“These men claim to be republicans, but are outdoing all the others in their efforts to oppose a number of the republican candidates.”

“These men are leading . . . the dirty fight . . . against Ainsworth”

Who were the leaders against Ainsworth? Two well known Newton men, Dr. Gastor Boyd and J.C. Johnston. The editor gave some back story related to the two men. He noted that Dr. Gaston Boyd, was “a life long democrat until he was defeated” in a recent election. It was observed that Dr. Boyd secured a promotion for his son when he was Newton’s mayor and appointed his “own son city clerk.”

J.C Johnston was a Republican with a total of 12 years of service in various capacities in county government including County Clerk and County Treasurer. The recently defeated candidate for sheriff, W.C. Johnston was likely a relative**. The editor of the paper noted: “after a long term in office, his [Johnston’s] luck changed.”

Johnston applied or ran for various positions from pay master in the general army to the superintendent of construction of the new Harvey County courthouse. He was not able to secure any of the positions and the editor noted that after not receiving the position under the McKinley administration “he abused McKinley.” In 1894, a suit was filed against him by Harvey County “to recover about $5,000.00 in fees which as county clerk and treasurer he had failed to pay into the treasury.” The editor concluded that “by this time he was out with practically all republicans” further noting that “these are the men that are leading. . . the dirty fight . . . against A.R. Ainsworth for Sheriff.”

Boyd and Johnston charged that Ainsworth was “guilty of compounding a misdemeanor about seven years ago.” They claimed that Ainsworth

“accepted $15 from James Riley for his agreement not to prosecute said Riley for crap shooting and he received $50 from Thomas Berry about 13 years ago for releasing him from custody when he was wanted in Nebraska for stealing horses and sheep. “

“We have investigated these charges”

Editor Peters set out to answer the charges. The first case was a muddled exchanged involving a forged check issued at Murphy’s Hotel and innocently cashed by Mrs. Van Aiken and a man by the name of Riley who was involved in an illegal crap game in July 1901. Peters was adamant, after talking with those directly involved, that Ainsworth had done nothing illegal. He summarized by noting that Ainsworth merely “recovered and returned to its owner the money obtained from Mrs. Van Aiken as a result of a criminal act . . . no extortion was involved.”

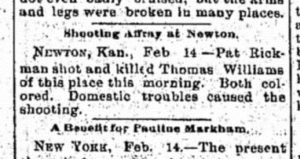

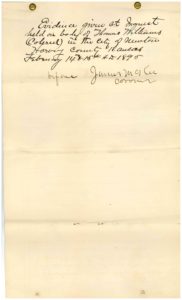

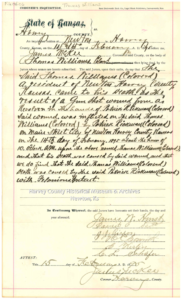

The second charge made by Boyd and Johnston involved the release of a man wanted in another state, Thomas Berry, for money. The editor concluded that it was a matter of poorly timed information from the sheriff in Nebraska that led to the release of the man charged with stealing horses and sheep.

Peters observed that these events transpired thirteen to fourteen years ago and Ainsworth has served in “honorable positions in the community” all of this time. “Nothing,” Peters continues, “is heard of this matter . . . until late day when Ainsworth is a candidate for sheriff.”

“Office of Sheriff“

Even with the conflict, A.R. Ainsworth was elected sheriff for Harvey County. The November 5, 1908 paper noted that “while the majority for Ainsworth was not as large as his friends expected, it was sufficient to place him in the office of sheriff next January.”

Principals Have Been Sued”

Ainsworth did file suit against Dr. G. Boyd, J.C. Johnston, and Joseph Hebert “for conspiring to defame his character on the eve of the election.”

Avery R. Ainsworth died at the home of his son, Clayton, in Newton at the age of 76 in 1921. Born in Ohio in 1845, he was in the 5th Ill Calvary, Co C during the Civil War. He married Sadie J. Corey in 1870, and the family came to Newton in 1879. The couple had three children, but only one lived to adulthood, Clayton. In Harvey County, he served as Newton City Marshall for several years, as Deputy Sheriff for two terms and one term as Harvey County Sheriff. He also served on the Newton Board of Education and was involved with the Episcopal church in Newton.

Notes:

- ** W.C. Johnston was likely a brother to J.C. Johnston, but at this writing (10/27/2017) it could not be confirmed.

Sources:

- Western Journal of Commerce, Newton, Ks 1901, p. 8.

- Evening Kansan Republican: 5 February 1900, 26 March 1900, 10 April 1900, 12 October 1900,25 March 1901, 21 August 1901, 2 August 190430 January 1905, 15 December 1905, 6 March 1908, 12 May 1908, 5 30 July 1908, 5 August 1908, 23 October 1908,5 November 1908, 20 May 1921, 24 May 1921.

- For more on the first televised Presidential debate: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/1960-first-televised-presidential-debate/