By Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Archivist/Curator

In any community there are stories that fall into a category that can only be called myths and legends. Stories that have been passed down through generations that may have started with a real event but embellishments have been added. Or stories that seem probable but cannot be proved by other documented sources. This is the case with Nellie Young’s account of an interaction that involved Jesse & Frank James on a Harvey County homestead.

In February 1936, an unknown reporter visited 90-year-old Nellie Young at her home “for the purpose of obtaining some first hand information regarding the life of early settlers.” The typewritten account is one of the many stories that are part of HCHM’s Archives.

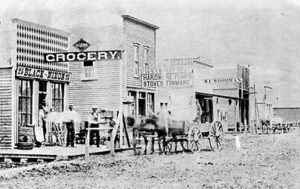

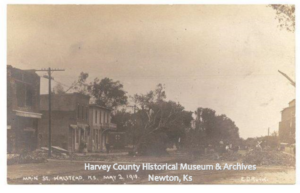

Nellie and her husband, H.N. Young and two small girls arrived in Harvey County in the spring of 1873. They had been living in Cameron, MO. The family homesteaded in Macon Township, seven miles west of Newton.

First Years

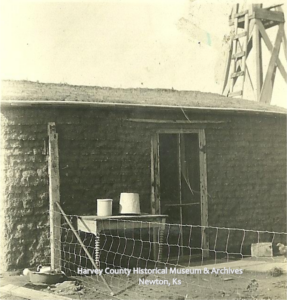

Nellie described living in a dugout for two years while her husband broke several acres where they were able to raise a few bushels of sod corn. In the spring of 1875, they were able to build a one-room sod house with a low flat roof. She described the house as sixteen feet long and twelve feet wide with walls three feet thick, a door at one end and one window on the side. Nellie recalled that the rattlesnakes enjoyed sunning themselves on that flat roof, much to her dismay.

Summer 1875

By summer 1875, they had developed a small acreage for wheat and it had been cut, bundled and stacked by the house. Nellie tells the story:

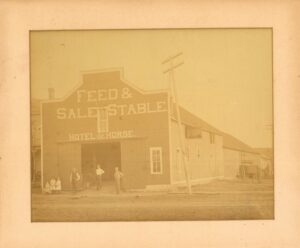

“At about 5 o’clock one afternoon the girls called my attention to two horsemen riding leisurely along the prairie trail in the hot August sun. We watched expecting them to pass, we were somewhat surprised to see them turn into our yard and go directly to our new straw stack.. . . they dismounted, unsaddled the horses and picketed them out near the straw stack. They then came to the door of our sod house and asked if the might stay at the straw stack over night, and after being told they should secure the permission of Mr. Young who was at that time out in the field at work, they remarked, ‘Well, we’ll stay anyway, our horses are tired and need rest.'”

“Splendid Looking Man”

Nellie noted that they did not have access to many newspapers. In fact, the only one they saw regularly was the St. Louis Weekly Democrat that a neighbor several miles away loaned to them. Even so, Nellie recalled, “I at once recognized our uninvited guest as being Jesse James and one of the other members of his notorious gang.” She felt that the newspaper pictures had not done him justice as Jesse “was indeed a splendid looking man. He wore a blue suit of expensive material and with his broad rimmed hat and fine leather belt filled with cartridges, and his holster buttoned over his revolver he was indeed the original of what the movies now attempt to imitate.”

She observed the horses were well cared for and the saddles and bridles “were of the heavy cowboy pattern and were of expensive leather, beautifully hand carved.”

They had given their horses feed from the Young’s “small pile which were we carefully hoarding to furnish feed for our own team.”

At that point Mr. Young came in from the field and agreed with Nellie’s identification – it was indeed Jesse James at their farm.

“A Restful Night’s Sleep . . .for the Guests”

Then, Nellie realized she would need to feed the “guests.” She recalled that she increased “the portions of our limited menu . . . we all ate heartily of boiled potatoes, and corn dodgers with sorghum molasses and Arbuckle’s coffee.”

Night came and Mr. Young was afraid that the guests would steal their horses if they were allowed to sleep outside, so he insisted that they sleep in the house. Nellie provided quilts and pillows and “they apparently enjoyed a restful night’s sleep on the floor of our shanty, while we slept but fitfully at the end of the room.”

“Chatting and Visiting Like Old Friends”

For breakfast she prepared a freshly killed chicken, fired potatoes and hot soda biscuits and coffee. Jesse and his friend did not seem to be in any hurry to leave and remained with the Youngs for close to two hours “chatting and visiting like old friends. . . Jesse told us he was returning from Texas and frequently mentioned his mother remarking that she disapproved of the long trips which he frequently took. When finally ready to leave Jesse inquired as to the amount of their bill and on being informed that there would be no charge insisted on leaving two silver dollars and bidding us a hearty goodbye. They mounted their horses and were soon out of sight as they crossed a ridge a mile to the east.”

Truth or Myth?

Did this really happen? The story is difficult to prove or disprove. In 1875, the James brothers and their gang were all over the United States. On December 8, 1874, they robbed the Kansas Pacific train at Muncie, Ks. They were in Kearney, Mo in January 1875 and by September at least some of the gang was in W. Virginia and Nashville. At some point in 1875, they reportedly cased the 1st National Bank in Wichita but passed on a holdup due to the high security of the huge basement vault. Documentation for this visit is also scarce.

It is possible that the James brothers were in Harvey County in August 1875 and that they stopped at a remote homestead for the night. At this writing we only have the memories of 90-year-old Nellie Young who shared her story in 1936.

Sources

- “Harvey County Pioneer Tells of Visit by the Notorious Jesse James in Early Days,” an interview of Nellie (Mrs. H.N.) Young, author unknown, typewritten copy, Archives, Harvey County Historical Museum & Archives, Newton, Ks

- About – Jesse James Photo Album

- Jesse James Timeline – Legends of America