The clues for this Harvey County Main Street include Old Settler’s Picnic, the transparent Anatomical Mannequin, Valeda, and the filming of the movie “Picnic.”

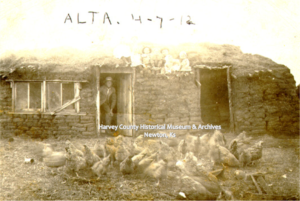

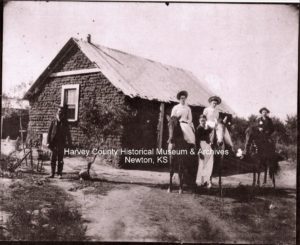

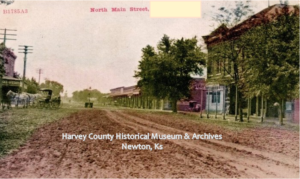

1873 Halstead

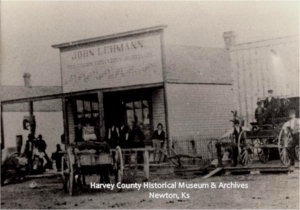

The Halstead Town Co. purchased 480 acres and platted a new town at the confluence of the Little Arkansas River & Black Kettle Creek.

The town was named for journalist Murat Halstead. G.W. Sweesy built a two story wood frame hotel at the site.

1877

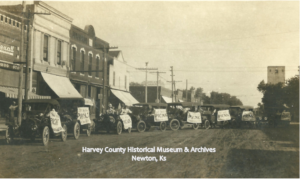

Halstead incorporated as a 3rd class city on March 12, 1877.

1887

First Old Settler’s Picnic. The event continues today and is Harvey County’s longest running event.

1902

Dr. Arthur Hertzler establishes a clinic and hospital. In 2002, the Hertzler Hospital & Clinic closed due to financial difficulty.

1955

The movie, Picnic is filmed in historic Riverside Park.

1965

The Kansas Health Museum, Halstead, opened as a “teaching” museum. Valeda, “the transparent woman,” and other exhibits were designed to educate about the systems of the body. Today the museum, known as the Kansas Learning Center for Health, continues to provide health education for all ages.

Valeda fun facts:

- She is 5’7” and, if alive, would weigh around 145 lbs.

- The model actually weighs 98 lbs.

- She describes the human body as various organs light up.

- The original mold was made by completely coating the body of a living, 28-year-old German woman with a rubber composition. This was allowed to harden, then peeled off to form the mold for Valeda’s plastic skin.

- Her aluminum skeleton is situated exactly as it is in the normal human body.

- In 1965, she cost $14,105.00.

1994

Federal Flood Control Project is completed, protecting the city from future floods.