by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

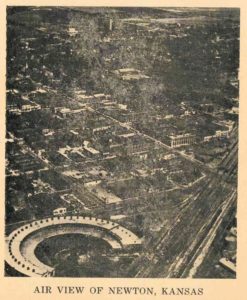

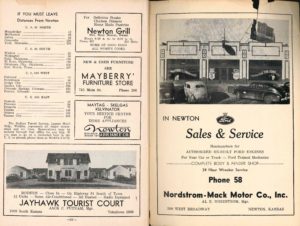

A booklet published by the Newton Chamber of Commerce in 1949 entitled The Newton Guide:Published for the Out-of-Town Visitor was recently donated.

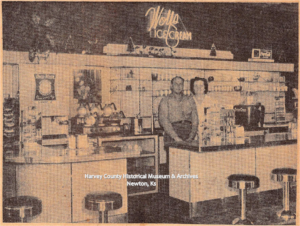

What was there to see and do in Newton in 1949?

S.E. McCall, President of the Newton Chamber of Commerce, wrote in the introduction;

“We cordially welcome you who are visiting Newton for the first time and to those who have visited here before, we extend a sincere ‘glad to have you back.'”

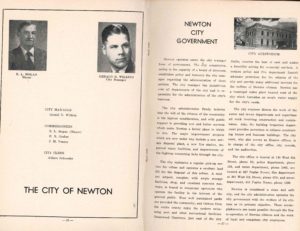

He noted recent improvements including the “organization of the Industrial Development Corporation, . . . new sewage disposal plant.. . . new fire station. [and] at least 100 new homes and new residential developments.”

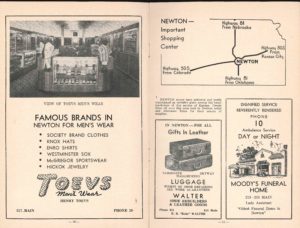

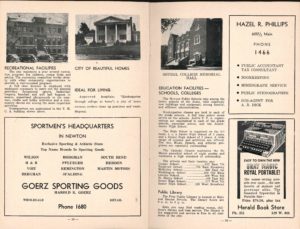

The purpose of the 33 page document was to highlight the selling points of Newton and surrounding area. Today, the pamphlet gives us a peak at the community at a specific point in time. We also get an idea of what was deemed most important.

Enjoy this trip back to 1949.

Newton Guide

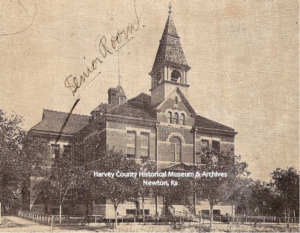

History of Newton

The early beginnings of Newton were briefly mentioned. The focus was on presenting Newton as “a modern city” with schools and churches “rated among the finest in our state.”