by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

While the Old Mill Building was saved and repurposed, not all were so lucky. In the late 1960s early 1970s, structures dating from the 1880s and 90s were torn down. This is the early history of a building that was not saved – the Newton Hotel.

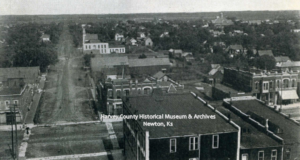

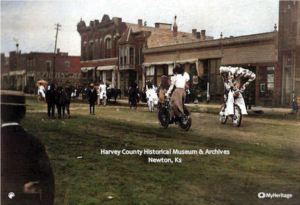

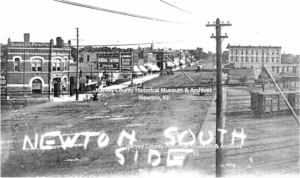

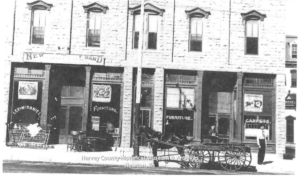

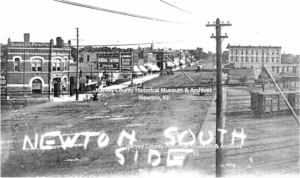

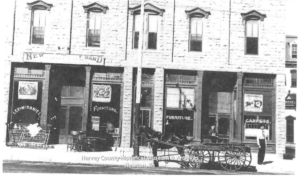

South of the tracks, Main street, ca. 1890.

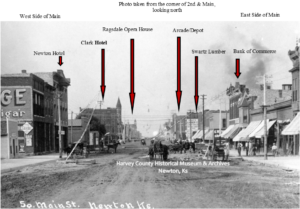

Main, south of the track, looking south, ca. 1890. Swartz Lumber Building on the left. Newton Hotel is on the right.

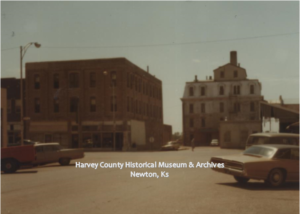

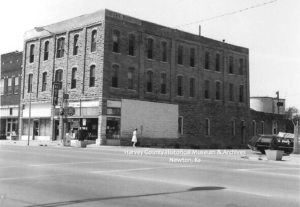

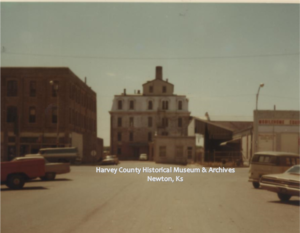

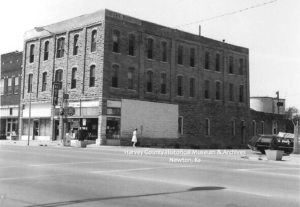

The Newton Hotel, 1970.

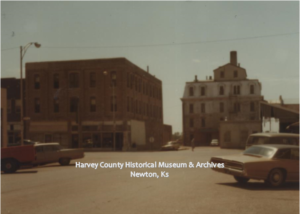

Newton Hotel on the left, Old Mill on the right, ca. 1970.

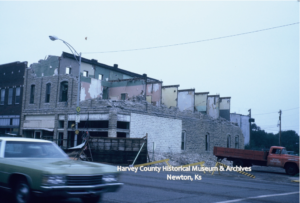

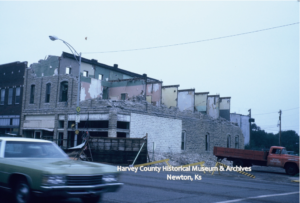

Photos of Demolition, ca. 1970.

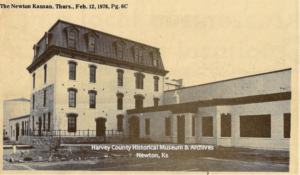

Newton Hotel Building, 225-227 N. Main, Newton, prior to demolition, ca. 1970

Newton Hotel Building, 225-227 N. Main, Newton during demolition, ca. 1972.

Newton Hotel Building, 225-227 N. Main, Newton, during demolition, ca. 1972.

For such an impressive structure, it was difficult to pin down the early history.

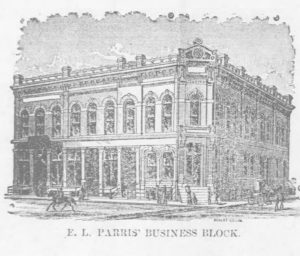

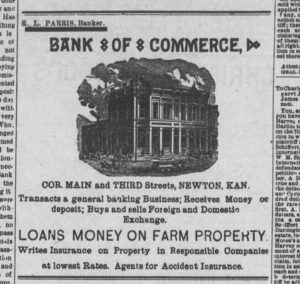

The late 1880s was a time of growth and optimism in Newton. The Ragdale brothers built a grand opera house at the corner of Broadway and Main in 1885. Many of Newton’s wealthy built homes along East 1st and West Broadway. Business were also growing along Main street on both sides of the tracks. E.L. Parris opened the Bank of Commerce at the corner of Main and 3rd, in 1888 south of the tracks.

225-227 N. Main

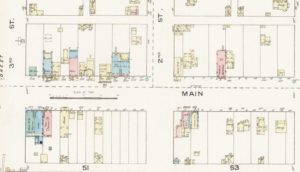

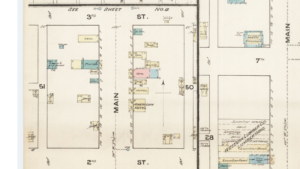

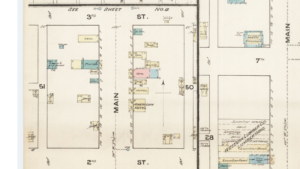

An 1884 Sanborn map shows a small stone structure at 225 Main identified as a furniture store.

Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1884.

A much larger stone structure is indicated at 225-227 Main on the Sanborn map in 1886.

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, 1886.

In 1886-87, Tin Works with George C. Jones, Tinner, and Bradt & Hubbard Hardware advertised a “New Hardware Store” located at 227 Main.

Newton Daily Republican, 27 September 1886.

” Should Do Good Business”

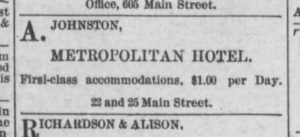

Next door, at 225 Main, the Metropolitan Hotel with restaurant opened in 1886, C. B. Chapman proprietor. The Newton Daily Republican noted “the dining room is handsomely fitted up. The Metropolitan should do good business.” L.W. Warner worked as clerk and Mrs Lizzie Beekwith was the cook. There were two waitresses, Miss Ella Grove and Miss Bertie Ingol according to the 1887 directory.

In 1887, Mme. French, a fortune teller, returned from Europe. The Metropolitan became her headquarters where she told “the past and future by planets and astronomy, brings parties together; places the charm upon the head and gives luck and prosperity.”

Newton Daily Republican, 28 July 1887.

By summer 1887, the Metropolitan Hotel was for sale. Described as “a large 3-story stone building of 30 well arranged and well ventilated rooms, and everything is in first-class order; is situated on Main street, south of the depot and is doing a fine business, every room being occupied.”

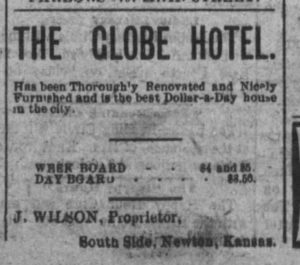

Over the next several years, the hotel underwent several changes of management. In 1888, under the management of J. Wilson the hotel was “thoroughly renovated” and renamed the Globe Hotel.

Newton Daily Republican, 13 December 1888

Boom and Bust

The 1890s were something of a reality check for Newton businessmen. On November 27, 1890 “fortunes were swept away in an instant,” when a financial panic swept through Newton. Eight banks closed and real estate plummeted. Many prominent businessmen went bankrupt, including E.L. Parris, financier of the Commerce Block at the corner of 3rd & Main.

Newton Kansan, 27 November 1890, p.1.

The Newton Kansan noted that “men who retired at night happy in the thought that they were on the road to wealth, awoke in the morning to find that the boom had busted and their wealth only a myth.”

No doubt the bust played a role in the turnover of owners and managers at 225-227 N. Main for the next seven years.

“There’s Money In It”

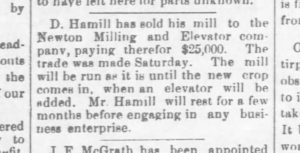

Optimism returned when the Santa Fe division headquarters relocated to Newton in 1897.

The editor of the Newton Daily Republican observed, “Now that prosperity has invaded Newton, some one should start up the old Globe hotel. With the right kind of a man in it, there’s money in it.”

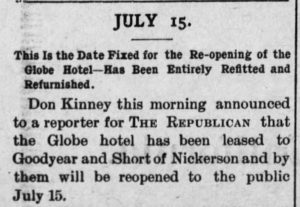

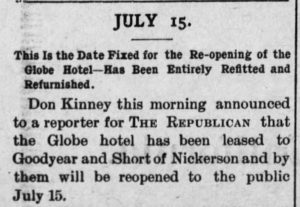

Someone took him up on it. A June 26, 1897 notice in the Newton Daily Republican announced the “Re-opening of the Globe Hotel.” The hotel under the management of Goodyear & Short from Nickerson, Ks had “refitted from top to bottom” including interior improvements and new furniture “making it one of the finest hotels in the city.”

Newton Daily Republican, 26 June 1897.

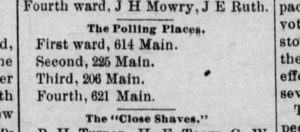

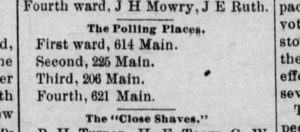

The building also served as the polling location for the Second ward throughout 1890s.

Evening Kansan Republican, 3 April 1899.

In 1898, the building became the Hotel Newton or more commonly the Newton Hotel. City council spent time at the May 19, 1898 meeting discussing the “exceedingly deplorable” conditions around Newton. First they discussed “the cellar of the Newton hotel and the building adjoining it to the south, . . . it was thought best to fill them up, as they were of no used and filled with odorous water.” They also planned to “tour the city and notify property owners to remove manure piles and clean out-houses. . . before warm weather sets in.”

The Weekly Republican reported July 1, 1898 on the meeting of the Newton Cyclists’ Association, which had chosen the Newton Hotel along with Frank Tyson’s restaurant, as “the official hotels for bicyclists” for an upcoming event.

Throughout this time, the proprietors of the hotel frequently changed. In 1902, Davis & Evans were proprietors and in 1905 W.C. Simmons took their place. By 1911, successful Newton hotelier J.W. Murphy was managing the business.

The Fire Marshal reported in November 1911 that several of the larger buildings in Newton including the Newton hotel, Duff & Son Furniture Co and the Opera house were adequately equipped with fire escapes.

“Cure Guaranteed”

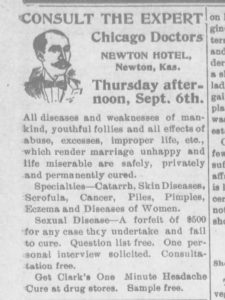

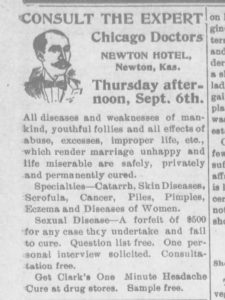

The hotel was a favorite stop for visiting experts including “the physicians and surgeons of the Chicago Curative Institute . . . cure guaranteed.”

Newton Kansan 24 August 1900.

Another frequent guest was “the Boy Wonder” who was skilled in “the science of magnetic healing.”

Evening Kansan Republican, 31 October 1906.

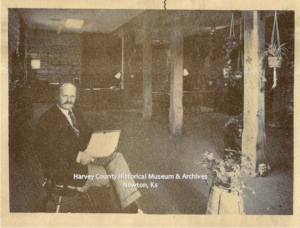

Several other business were located on the first floor of the building including Lee & McDaniel New & 2nd Hand Furniture, and the Home Furnishing Store.

Lee & McDaniel Home Furnishings, 3rd & Main, Newton, Ks ca. 1910.

Photos of the Newton Hotel

200 Block Main, west side, Parade, ca. 1906. Red arrow indicates the Carnegie Library Building, Newton Hotel large building on the right corner of the photo.

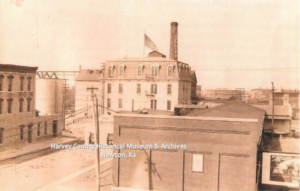

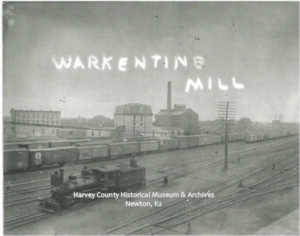

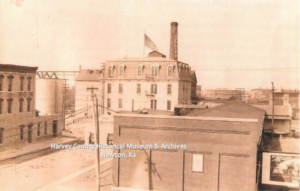

Newton Milling & elevator Co., Hotel Newton on the left, ca. 1922.

Sources:

- Newton Daily Republican: 20 September 1886, 26 September 1886, 18 February 1887, 2 July 1887, 15 January 1889, 15 January 1897, 1 June 1897, 26 June 1897.

- Weekly Republican 1 July 1898.

- Newton Kansan: 19 May 1898, 23 November 1911.