by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

This article is part of a series, Looking Back at the Oldest Buildings on Newton’s Main Street.

The buildings on the east side of the 200 block of Main in Newton are some of the oldest buildings in Newton, several dating between 1886 and approximately 1895, including the buildings at 212 and 2164Main. Although this post will focus on 214, the adjacent building was constructed at the same time and still retains many features from 1889-1895. These features include the cornice and the original shape of the windows on the second floor is also apparent even though they have been brick in.

A Wood Frame Structure at 214 Main

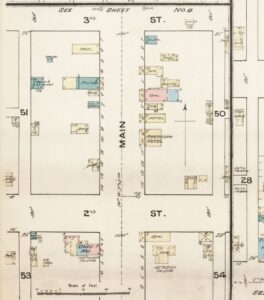

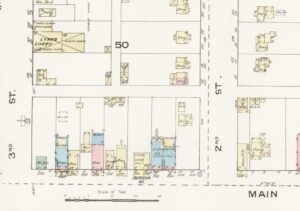

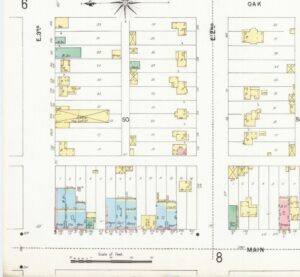

According to the 1884 Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps of Newton, there was a small, wood frame building, identified as a drugstore, located at 214 Main.

As the block begins to fill in over the next several years the small drugstore remains at 214 with a grocery store at 212.

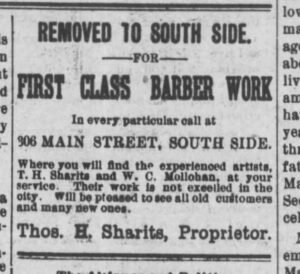

In 1884, Thomas H. Sharits moved his barber shop to 214 Main for a short time. Tom Sharits was described as a “good barber, has a neatly furnished, pleasant shhop and gives general satisfaction to his customers.” He also had a reputation as “the great Jack Rabbit destroyer.” The papers mention his hunting ability several times including successful coyote hunts. Throughout the 1880s and 90s, Sharits moved the location of his barber shop several times.

The earliest Newton City Directories also indicate that this building also served as a boarding house with two boarders living at 214 Main in 1887.

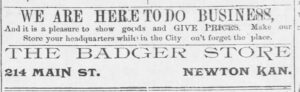

In 1889, the Badger Store, which carried a bit of everything, was located at 214.

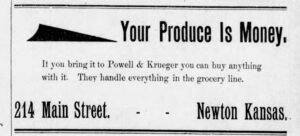

Another business that located in the building was Powell & Krueger. In 1892, they advertised that “you produce is money . . . you can buy anything with” at their store located at 214 Main.

A New Brick Building at 212 – 214 Main

An exact date for the buildings at 214 and 216 Main has not been definitely established, however by 1896, there are 3 substantial brick and stone buildings at 216, 214, 212 Main, perhaps constructed at the same time. A second hand store was located at 216 Main, a General Store at 214 and a Bakery at 212.

The March 28, 1902 Newton Daily Herald noted that one of the leading enterprises on the south side is the grocery and bargain store of W.D. Congdon.” After one year in his new location at 214 Main he “has built up an extensivve trade.” The second floor had rooms for boarding.

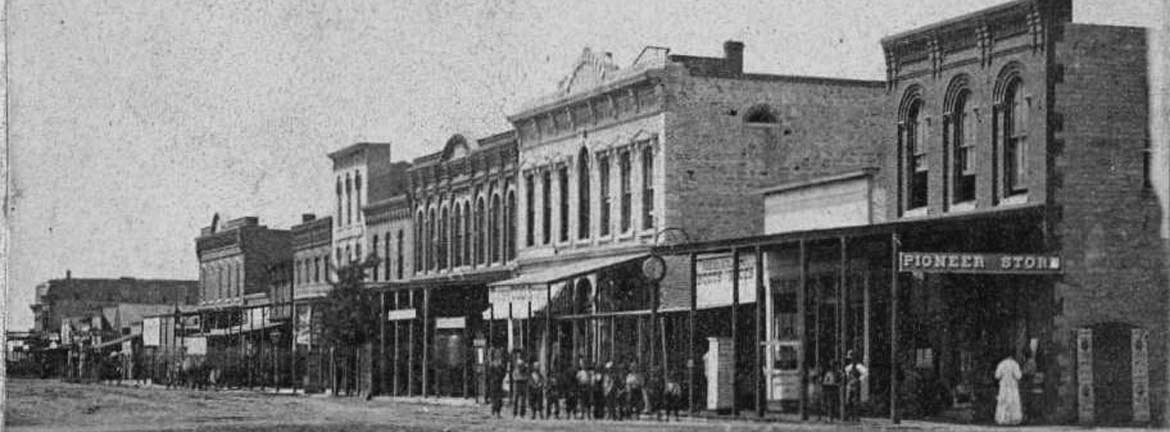

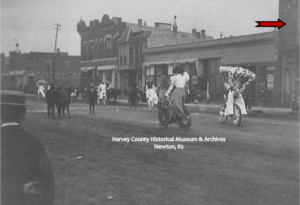

200 block of N. Main, Newton, KS, c. 1910. 214 Main indicated with an arrow. Businesses on the east side of the street are identified in a note glued to the back of the mounting. The businesses are Star Grocery, Up-To-Date Steam Laundry, a junk store with Ringling Bros. advertising on it, Toevs Bros. Grocery, Cavneys (sp.) Wallpaper Store, Pete Park’s Meat Market, Kruegers Grocery Store and then Young’s Grocery Store in 300 block.

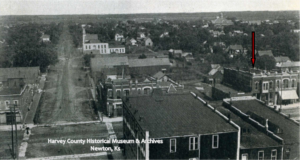

Newton. c. 1910. Intersection of east 3rd and Main. 214 Main is indicated with an arrow. Looking east down East Third Street from Main. Church with steeple, upper left center, is German M. E. Church, 215 E. 3rd, (1905 Newton City Directory), later purchased by First Church of God.

The front facade underwent significant change between 1920 and the late 1930s to the current look of the building. The second floor bay window and the tin cornice removed. The second story windows were also changed to a square shape. The general appearance of the front facade was more flat.

The Movie Theater

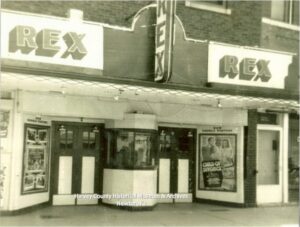

In the 1940s and 50s the building provided a space for one of several Newton movie theaters.

Exterior black and white photocopy showing Roxy Theater, 214 North Main, Newton, Ks. LaVern Hein Plumbing and Heating business to the south (right side of picture) and a bar to the north.

Over the years these two buildings have housed many varied businesses as Newton changed and grew. The appearance of the two buildings also underwent changes with each decade. Although the front facades have been altered, the buildings at 212-214 Main are part of a small group of structures that remain from the 1880s-1890s.

Additional Sources

- Weekly Republican: 20 September 1889

- Newton Daily Republican: 16 July 1890

We felt we were as important as any big city kid because the pool was so nice.

Ok, I lived in Newton in the 60’s and spent quite a bit of time at the pool. Swam again in it in the summer of 1987. Could any explain why the water was always so cold at the pool? I can still remember swimming and then laying on the hot concrete to warm up. It was a great pool and one of the largest I have seen for a public pool.

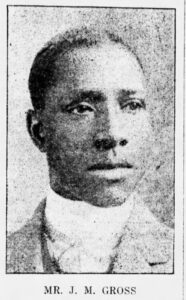

The above comments regarding the treatment of Blacks makes me sick. I was born and raised in Newton and I am so glad I didn’t have to know about that terrible time in our history. One of my best friends in High School was a Black girl and my family and hers accepted our friendship without any problems. History can really prove to be painful at times.

Thank you for your comment. History sometimes is not pretty or what we might wish it would have been. We (the museum staff) believe that it is important to tell these stories to remind ourselves and those reading that people really did get hurt, did experience discrimination and injustice right here in Harvey County, Kansas. We hope that in telling the story we can give validation to those that had to go through these events and hopefully we all can learn from it. We are, however, sorry if it was painful for you to read.

I remember taking swimming lessons each spring after school was out for the summer. My parents chose for us to go to Peabody’s pool over Newton because we were told the Peabody pool was heated and Newton’s wasn’t.