Originally published on January 31, 2013, on BlogSpot –An Ordinary, Amazing Woman: Mary Rickman Anderson Grant

by Kristine Schmucker, Curator

“Mrs. Mary O. Grant, colored, aged 95, one of the oldest residents in this county died Tuesday night at 11:30 . . . “

|

| Mary Rickman Anderson Grant Harvey County Pioneer Photo courtesy Jullian Wall |

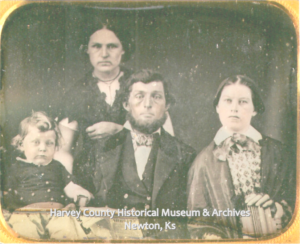

Mary’s story starts in Sparta, White Co., Tennessee where she was born April 1835. Her father’s name was Nathanial Rickman and her mother’s name may have been Sophia. In the 1860 Census, Mary is listed as the head of household with four children, Joseph, America, Lucy and Tennessee. At some point she met and married David Anderson and moved to Ohio. David Anderson served in the Civil War in Co I 14th Reg. U.S.C.T., which was the same regiment as Mary’s brother Joseph Rickman. Perhaps he introduced Anderson to his sister and they got married. By 1870, the entire Anderson family was living in Clemont County, Ohio with David listed as head of the household with three more children, James Wayman, Thomas Jefferson, and Nathanial. A daughter, Carrie, is born later that year.

Homesteading on the Prairie

In 1871, the Anderson family decided to move to Kansas. Like many black families they saw the opportunity to own land. The Homestead Act of 1862 allowed a citizen to file “first papers,” pay a $10 fee and claim 160 acres of land in the public domain. The Anderson family left all that they knew and traveled by covered wagon to Emporia, Kansas for a chance to own their own land. From Emporia, they traveled to Florence, Kansas, where the family stayed in a dugout while David Anderson went to the homestead site in Pleasant Township, Harvey County. Here he began building a new home but met with misfortune almost immediately. One of the horses died, leaving only one older horse for the difficult work of breaking the prairie sod. Anderson decided to trade the horse for a pair of oxen and continued to work on improving the claim.

|

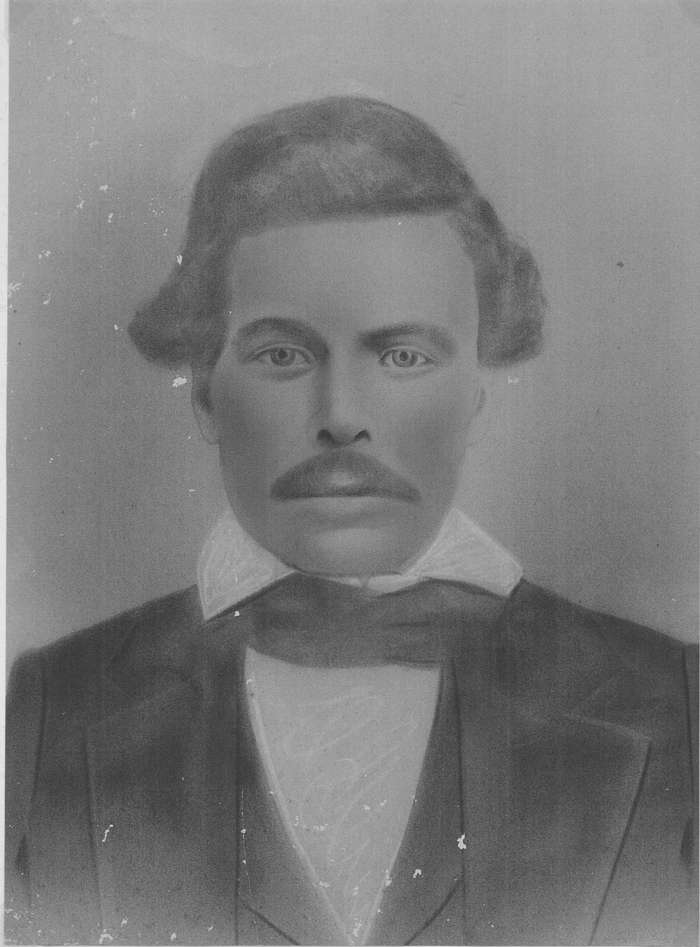

| David M. Anderson Mary’s 1st husband Photo courtesy Jullian Wall |

Anderson filed for a homestead in Harvey County, Pleasant Township, Section 26, but he did not live to see the fruits of his efforts. David died on April 3, 1872, leaving Mary with eight children on the prairie. He was buried on the homestead.

|

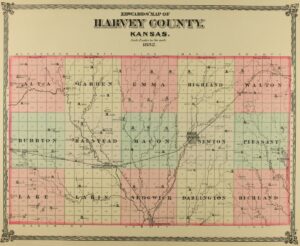

| 1885 Atlas Pleasant Township, Harvey County |

Death from accident or illness was a constant threat to the new settlers. In 1872, Mary’s daughter, America Turner died. Three granddaughters, Estelle & Linnie (1879) and Alta (1881) also died and were buried in the family plot on the homestead.

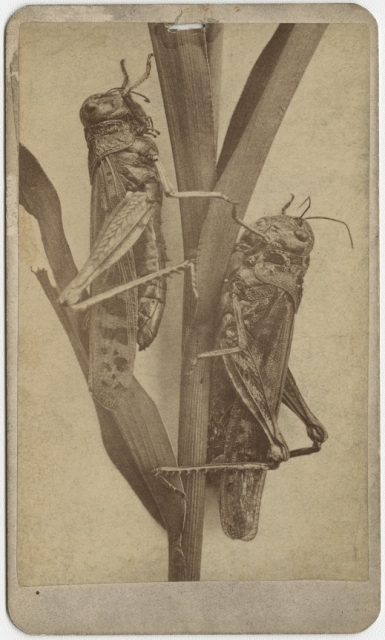

“At the end of that time every stalk of corn and garden and every vestige of vegetation that was green enough for them to eat simply was not. It did not exist. All paint and even the old black boards and logs were eaten until they looked like new lumber.”

(Anderson,Rickman, & Rossiter Family Reunion Picnic, by Marguerite Huffman, ca. 1981)

|

| http://www.mnopedia.org/multimedia/minnesota-locusts-1870s This species was not a grasshopper, rather a Rocky Mountain Locust which went extinct around 1902. See also http://www.hcn.org/issues/243/13695 |

The Anderson family confronted another challenge of the prairie. In 1876, a prairie fire broke out near Whitewater, south and east of the Anderson claim. Soon the flames were sweeping across Harvey County in a ten mile wide swath. A neighbor lost his barn and 20 head of cattle. Young Jefferson Anderson was home alone at the time. He did the only things he could think of – he turned the oxen loose and chased them to the creek. Amazingly, the house was spared. The main loss was of a pig pen and a stable.

|

| Orison Grant Wearing his Civil War Uniform Mary’s 2nd husband Photo Courtesy Jullian Wall |

Forty-six year old Mary Anderson married Orison Grant, a Civil War veteran, in September 1878. A Justice of the Peace performed the ceremony. Grant was 61 at the time according the marriage license.

Grant had also come to Kansas in search of land to call his own. He settled on a claim in Highland Township in 1871. After their marriage, the Grants sold the Highland claim in two parts; the first in 1885 for $1350 and the second in 1886 for $2000.

|

| 1885 Atlas Highland Township, Harvey County |

In 1889, Mary made the final $8.00 payment on her homestead in Pleasant Township – the farm was officially hers.

Orison Grant died February 3, 1893. His obituary noted that “people that knew him intimately dubbed him ‘General’ which title always pleased him. He was respected by all who knew him.” (Newton Kansan, 3 February 1893, p.3)

Keeping the family together

Mary stayed on the homestead until 1910. At that time she sold the farm for $8,500. Family was important to Mary and it was important to her that the family stayed together. When she moved to Newton, she had the six members of the family who had been buried in the family plot on the farm moved to Greenwood Cemetery, Newton.

For the next thirteen years Mary lived with her daughter, Lucy Rickman Mayfield at 330 E. 6th, Newton. Mary Grant, Harvey County pioneer, died August 1, 1923 at the Mayfield home.

|

| Mary Rickman Anderson Grant and Lucy Rickman Mayfield |

During the month of February, in honor of Black History Month, we will be featuring related stories from Harvey County. Much of the information on the Rickman/Anderson/Grant family is based on oral traditions preserved by Marguerite Rickman Huffman & June Rossiter Thaw and research by Karen Wall. We are grateful for their willingness to share the stories of this Harvey County family.

Sources

- Anderson,Rickman, & Rossiter Family Reunion Picnic,” by Marguerite Huffman, ca. 1981 in Harvey County Residents Box 1B, Rickman/Anderson File Folder 35)

- Evening Kansas Republican, 1 August 1923, p. 5.

- Newton Kansan, 3 February 1893, p.3

- Karen Wall, Find-A-Grave, “Mary Rickman Anderson Grant.”

Visit http://hchm.org/ for more information on the Harvey County Historical Museum & Archives.