by Hannah Thompson, HCHM Director

Today’s post is by Hannah Thompson, HCHM’s new director. Her research interests include late 19th century Spiritualism. The influence of the national interest in Spiritualism can be found in Harvey County newspapers.

“Notorious” Characters

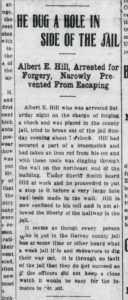

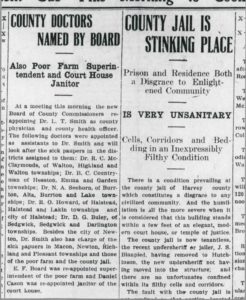

A 1903 article in The Evening Kansan-Republican mentioned several “notorious” characters from the seventh voting district, which Harvey County was then a part of.[1] Alongside “Iron Jaw” Brown and Carrie Nation, the paper mentions Mary Elizabeth Lease who “is now playing the role of an advanced spiritualist in New York City.”

“The JoAnn of Arc of the Kansas Populist Craze, 1892”

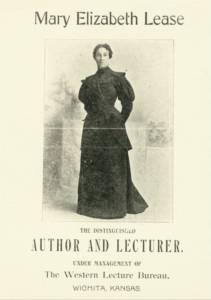

But who was Mary Elizabeth Lease, and why was she notorious? Born in Pennsylvania in 1850 as Mary Clyens, she followed the then-typical path for a woman of the 19th century: she met and married a man (Charles Lease) and had several children. When her husband’s pharmacy closed in 1874 due to a nationwide financial panic they moved from Kingman County to Texas, ultimately finding their way, with their four living children, back to Kansas and settling in Wichita.

It was there that Mary Lease began working for the Union Labor Party and kicked off her career in political activism as an engaging speaker. She was passionate about women’s and African American rights, and became a strong proponent of what would become the Populist Party.

The Populists or “People’s Party” was a major left-wing political force in the 1890s that held strong anti-bank and anti-railroad sentiments. It was supported mainly by farmers in the West and South and ultimately merged with the Democratic Party in 1896. Like the Prohibition Party, the Populists encouraged the involvement of women–keep in mind the 19th Amendment which gave women the right to vote was not passed until 1920!

Lease’s speeches were inspiring to many, but the fact that she was a woman worked against her, as her outspokenness was seen as “unwomanly.” She was nicknamed “Mary Ellen” by newspaper wags, so that they could call her “Yellin’ Ellen” or “Mary Yellin.’” The New York Tribune went so far as to accuse her of being a “mob leader”:

“But there is this to be said, of which there can be no denial, that Mrs. Lease upon the political platform or stump, uttering invectives more than masculine, and appealing to the brutal passions of the mob rather than to the calm sense of reasoning men and women, must be treated the same as any other mob leader, male or female. She cannot shelter herself behind her sex while appealing to bloodthirsty passions and inciting lawless riot.”[2]

The quote most often attributed to her, wherein she (supposedly) told Kansas farmers to “raise less corn and more hell” actually was not hers and may have been invented by reporters. When asked about the quote she denied it as her own, but agreed with the sentiment since she thought “it was a right good bit of advice.”[3]

Some blame Lease for the failure of the Populist Party in 1894 to elect a wide swath of officials. This is due to her contrariness and argumentativeness when she openly criticized the 12th governor of Kansas, the Populist Lorenzo Lewelling. She believed that he discriminated against her and tried to remove her from an appointed position due to her desire to bring women’s rights and temperance to the forefront of Populist Party concerns. Whatever the truth behind their disagreements, Lease found herself ostracized from the party, effectively putting an end to her political career.

The 7th District’s very Own Notorious Character.

By the time of the 1903 article in the Evening Kansan-Republican reporting on her activities, Lease had divorced her husband and was living in New York. It was around this time that her interest in Spiritualism grew, or at least became apparent in the historical record. Spiritualism was essentially the idea, not quite a religion but certainly closely tied to belief and faith, that immortality could be empirically proven by making contact with the afterlife via mediums. Lease presented at a Connecticut Spiritualist convention in 1901 a lecture titled “If a Man Die, Shall He Live Again?” wherein she described historical figures who believed in life after death, exclaiming that the Spiritualists of the time also knew life after death to be true.[4]

It’s interesting, then, that someone who shone brightly for such a short period of time, and was derided in newspapers for being “unwomanly,” “over-zealous,” and “turbulent and inflammatory,” would have her life not only tracked by a Newton newspaper but treated what seems to me to be a sense of grudging respect and maybe even pride.[5] Sure, she was a “notorious” character, off in New York calling forth spirits from beyond the grave as she “used to call forth Populist victory from windy caves of Kansas,” but she was 7th District’s very own notorious character, and they claimed her openly.[6]

Sources:

[1] Today Harvey County is in the 4th voting district.

[2] New York Tribune, Aug 13, 1896

[3] Topeka State Journal, Topeka, KS May 25, 1896

[4] Kuzmeskus, Elaine M. Connecticut in the Golden Age of Spiritualism.

[5] The Representative Minneapolis, MN June 10, 1896; New York Tribune, New York, NY Aug 13, 1896

[6] The Evening Kansan-Republican, Newton, KS Aug 28, 1899