by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

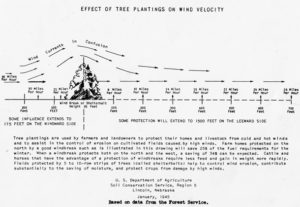

The creation of shelterbelts and windbreaks in the late 1930s and early 1940s, involved the cooperation of individual farmers, the US Forest Service, the Civilian Conservation Corps and the Works Progress Administration. During the Dust Bowl years, the effects of years of over working the prairie became obvious.

While campaigning for president in Montana, Franklin D. Roosevelt came up with the idea of wall of trees to combat hill-side wind erosion. His initial idea was a single solid wall of trees several miles wide running from the Canadian border to the Texas panhandle. A more realistic plan called for a series of walls from North Dakota to Texas.

Shelterbelt Project, major planting areas, 1933-1942. Credit: US Forest Service, Wikimedia Commons CC.

By 1942, there were 220 million trees, stretching 18,600 miles from North Dakota to Texas. The Shelterbelt Project was a successful federal program. The goal was to reduce erosion and lessen water evaporation from the soil of farm lands across the United Sates, in addition to reducing the amount of dust pollution from the wind storms.

Harvey County, Ks

The Harvey County Extension Office played an important role in providing farmers with the information and trees to implement these measures in Harvey County in 1939-1943. The Annual Reports written by H.B. Harper, Harvey County extension agent, provide insight into the farmers that participated, the demonstrations given and the success of the program in Harvey County.

“Windbreaks have Become Rather Popular” 1939

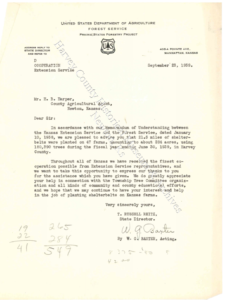

In 1939, a section titled Farm Forestry is included in the Annual Report of the Harvey County Extension Agency. H. B. Harper, Harvey County Agricultural Agent, noted that Harvey County was involved with the Prairie States Forestry Project with the purpose to “promote the planting of trees.” With cooperation from the Forest Service, Harvey County farmers were able to plant 284 acres of trees on forty-seven farms.

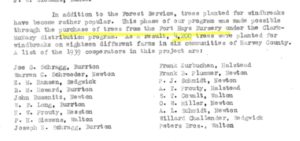

List of Farmers Participating in 1939

Harper also reported that “trees planted for windbreaks have become rather popular.” In 1939, 4,200 trees from the Fort Hays Nursery were planted on eighteen farms in Harvey County.

List of Participants in 1939.

He noted that the purchase of the trees was possible under the Clark-McNary distribution program.

Letter to H.B. Harper, County Agricultural Agent from W.G. Baxter, US Dept of Agriculture, Forest Service. 23 September 1939. Harvey County Extension Collection, HCHM Archives, Newton, Ks.

“More Enthusiasm Must Be Mustered” 1940

In 1940, Harper reported that 40 farms had shelterbelts “using 133,252 trees is a major accomplishment.” Demonstration planting meetings were held at two farms, Jonas Voran’s farm, located in Garden Township, and Waldo Voth’s farm in Pleasant Township. Despite Harper’s optimism in his opening reports, the tone for section on “Farm Forestry” was subdued. He noted that “more enthusiasm must be mustered into 1941 if Harvey County is to achieve as much as it should in the worthwhile project.”

1940 Annual Report Projects

“It might happen here.“

“But it can’t happen here.”

“But it can’t happen here.”

“Good care . . . will insure any farmer an excellent wind-break”

“Needed to Prevent Erosion”

“Needed to Prevent Erosion”

“Demonstrating the planting of a windbreak”

“Demonstrating the planting of a windbreak”

“Must be protected from rodent injury.”

In 1940, nineteen miles of trees were planted on forty-two farms. Adding the number of trees to the 1939 number, a total of 40.4 miles of trees planted on 89 farms. Harper concluded his 1940 summary noting that “land use planning is a new baby in Harvey County. Through community and county planning committees, we are assured of a real progress in 1941.”

“Popular This Year” 1941

In the 1941 Annual Report, Harper noted: “The program instituted through the forestry service four years ago has been very popular this year.”

“Demonstration on the Correct Method.”

“Farm Shelterbelt”

A.C. Dettweiler, Halstead Township, received acknowledgement for his farm and the successful shelterbelt that was 3 years old in 1941.

“Tremendous damage” 1942

“Tremendous damage” 1942

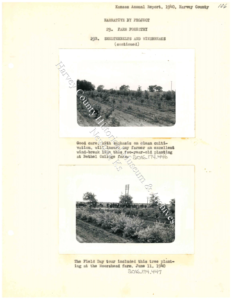

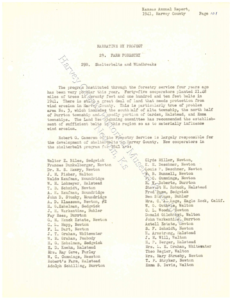

In 1942, the report included a list of farms participating in the program, noting that “tremendous damage was experienced on many shelterbelts and windbreaks June 12, 1942, but all have recovered.”

“Most Widely Accepted Project” 1943

“Most Widely Accepted Project” 1943

The 1943 report was the last one to specifically mention Farm Forestry, Shelterbelts & Windbreaks. Harper noted briefly that there were “73 miles of shelterbelts growing on 154 farms . . .. this was one of the most widely accepted project of this nature to be promoted in Harvey County.” Harper concludes by noting that the project will be available again next year.

Great Plains Shelterbelt Project

Today, the Great Plains Shelterbelt Project continues to promote this proven conservation practice across the U.S.

Sources:

- Harvey County Extension Agency Collection, Harvey County Historical Museum & Archives, Newton, Ks.

- Orth, Joel. “The Shelterbelt Project: Cooperative Conservation in 1930s America.” Agricultural History, vol. 81, no. 3, 2007, pp. 333–357. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20454725.