by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

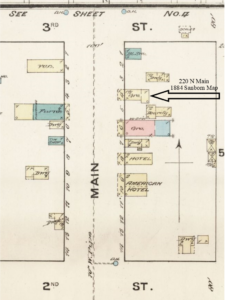

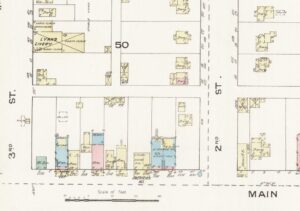

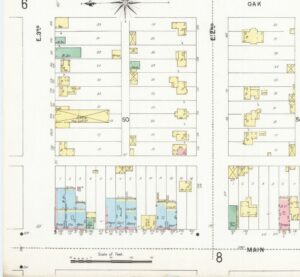

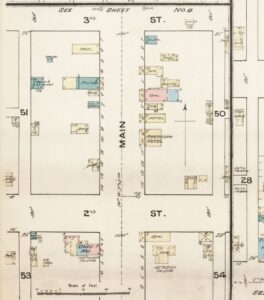

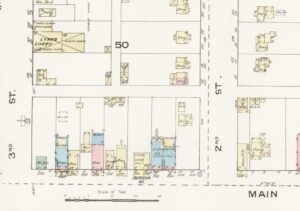

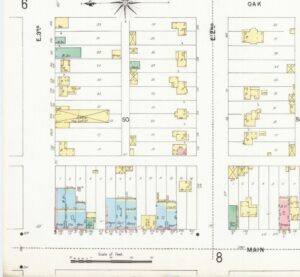

The building at 220 N Main is an unassuming structure that often gets overlooked when pointing out Newton’s oldest buildings. According to the Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, there was a wood frame structure identified as a grocery at 220 N Main as early as 1884. Photos, the Sanborn Maps and Newton City Directories, provide evidence that there has been a building at 220 N. Main continuously since 1884.

Tracing the Early Businesses

The trail of businesses in the building in the earliest years are difficult. At different points 218 Main is also part of the business. In addition, businesses moved quite a bit as partnerships were made and dissolved. Businesses also frequently moved to a different, maybe better location. Sometimes the move was just next door.

Groceries, Boots & Tin

W.P. Brown

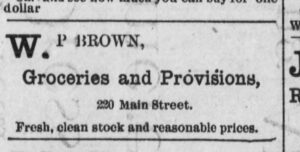

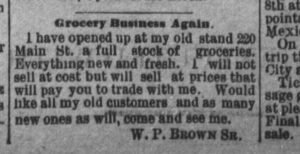

Between 1885 and 1887, W.P. Brown operated a grocery store and lived at 220 Main. Brown also added on to the back for a real estate office.

Brown apparently moved his business in and out of the building several times. In 1889, he again had his grocery at “his old stand” 220 N. Main.

On June 29, 1889, a notice in the Newton Daily Republican reported that a boot shop operated by C. Hensy had moved from 220 to 114 E 3rd.

The 1896 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map indicates that there was a Tin Shop located at 220 N. Main with “specials,” although the back part of the building remained wood frame. “Specials” on the maps indicated that modifications had been made to the building because of the business it housed. Perhaps this is when the current facade of the building was installed. Unfortunately, other than the Sanborn Maps, there is no mention of a tin shop at this location in the newspapers or directories.

The Meat Market at 220 N. Main

Peter Peace Park

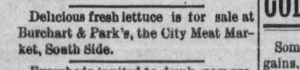

By 1890, one business has settled in, Peter Park’s City Meat Market. At first Park was in a partnership with Sam Burchart, however, it dissolved 9 February 1894. Park continued on with his Meat Market at 220 N. Main.

Peter Park had come to Newton, Ks to establish a life for himself. Park was born on 14 April 1853 in Orkney Island, Scotland. At the age of 18, he, with his brother William, came to Kansas and by 1871 they were living on a 80 acre claim in the area of what today is West Broadway. On 18 January 1872, he married Margaret Robertson, also a native of Scotland. They had at least two children, only one that lived to adulthood. To make a living for his family, Park opened a meat market.

The Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps from 1901 show the 200 N. Main block more complete, and the building at 220 with a long rectangular shape.

Interior of a Meat Market or Butcher Shop

While there are not interior photos of Peter Park’s City Meat Market, there are descriptions and photos of others in the area. Frieda Pankratz Suderman recalled visiting one as a child.

“We had two butcher shops where huge quarters and halves of beef were hung with big steel hooks over pits filled with sawdust. The meat was cut as it was sold, and scraps were dropped into bloody boxes that stood under the thick circular wooden chopping tables. The scraps could be had for the asking if you were poor or had a dog. “

At about the same time of Park’s City Meat Market, Abe Dettweiler had a butcher shop in Halstead that and there is a photo. The photo shows the long cutting table, large hooks on the wall, and two scales. The City Meat Market would have looked much the same.

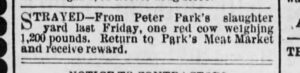

Running a butcher shop was not without challenges. In 1898, “one red cow weighing 1,200 pound” strayed from Park’s slaughter yard.

In addition to operating a small business, Park was active in the local Scottish society, known as the Harvey County Scottish Society. Many times the club met at his home. In February 1901, the Scots Club celebrated the birthday of Robert Burns at the home of Peter and Margaret Park. At that time there were of fifty members.

Park died suddenly at his farm two miles west of Newton October 23, 1902. The written obituary noted that

“he had always been a remarkably strong man and hardly knew what it was to suffer pain. . . a strong, good man, a quiet, law-abiding citizen. In his death the community sustains a distinct loss.” (Evening Kansan Republican 24 Oct. 1902).

Park worked at both his meat market and farm until a day before he died at the age of 49.

Peter Park, Jr

For a short time the Meat Market was operated by T.D. Ragsdale, but by 1911, Park’s nephew, Peter Park, Jr, was the proprietor of the Meat Market at 220 N. Main. He operated the business until his death in 1929.

Photos & Businesses of 220 N. Main

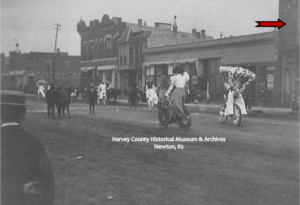

1899 Street Fair

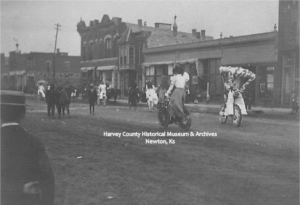

The earliest photo of the 220 N. Main building was taken in October 1899 during the Newton Street Fair and during Peter Park’s ownership.

After the Park family no longer ran the meat market, the building housed a number of different types of businesses.

1910 – “Valuable Truths” Revival Meetings

An “instructive” Bible study was held at 220 Main by Evangelist N.E. Baker from Arkansas City in September 1910. With a Bible class at 7:30 and 8:00 pm preaching all were encouraged to come to this free event. The announcement noted; “these meetings are quite instructive, and the teacher gets down into the scriptures and brings for valuable truths.” (Evening Kansan 21 Sept. 1910)

1930s – 1940s – Beauty & Barber Shops

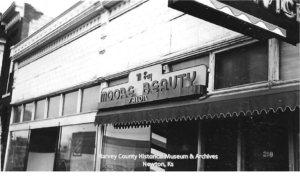

220 and 218 N Main, M. Fay Moore Beauty Salon, 1935. 1943 Newton City Directory lists Oscar Lee as a barber at 218 Main and Fay Moore as beautician at 218 B Main.

1950s – 2021 – Billiards and Taverns

In 1954, Newton Billiards was located at 220 N. Main. J& K Tavern opened for business in the early 1960s. Throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s, Jay’s Bar was located at this location.

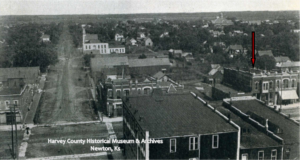

Newton. 1961. American Legion Parade. Newton High School band is marching north on Main Street. Businesses in the background, left to right: Earl Brown Wholesale Candy & Tobacco – 226 N. Main, Supernois Furniture – 224 N. Main, Hazel Phillips. Public Accountant – 222 N. Main, Wiens Realty & Carl’s Barber Shop – 218 N. Main, Stukey’s Beauty Shop – 216 N. Main, Roxy Theatre – 214 N. Main.

In 1984, Legal Tender, advertising “Live Entertainment” in celebration of tenth year in business.

Today, 220 N. Main, an unassuming building with a long history, is the location of Jay’s Place.

Sources

- Newton City Directories:1885, 1887, 1901, 1905, 1911, 1913, 1917, 1919, 1931, 1934, 1938, 1945, 1946, 1954, 1960, 1965, 1974, 1984.

- Evening Kansan Republican: 7 Oct. 1899,

- Newton Daily Republican: 14 February 1887, 20 February 1894