by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM

What is it?

In our collection at HCHM is a small oddity. The object is circular with sawtooth edges. Engraved on the object are “Murphy 10 Hotel” and is identified as a key to a room at the hotel. While I cannot quite imagine how the object would function as a key, I think it might be the tag attached to a room key, telling the visitor which room is his or hers.

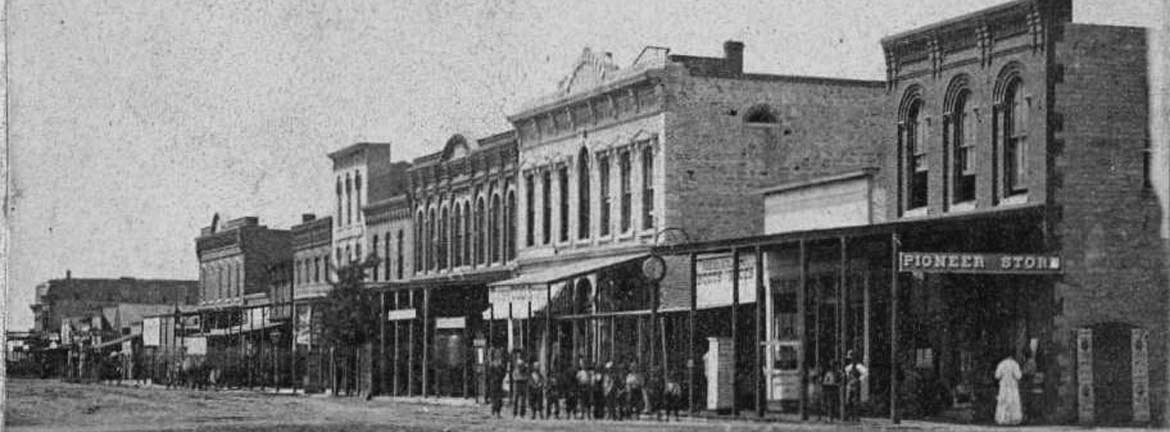

Murphy’s Hotel, 413 N. Main

Several hotels were located within walking distance of the AT&SF Depot within weeks of the railhead stopping in Newton in July 1871. The Rasure Hotel later known as the Howard House and replaced by the Clark Hotel was very conveniently located at the corner of 4th & Main on the west side. It was perhaps the first hotel in Newton.

In the 400 Block of north Main alone, there were three large hotels. One was constructed in the 400 Block on the west side. The July 13, 1883 issue of the Newton Democrat reported that “Frank Zurcher removed the old buildings from his lot opposite the depot on Main street and will commence the erection of a fine building immediately.” A fine new building soon occupied 413 N. Main. I. Isaacs, former proprietor of the English Kitchen, oversaw the new hotel known as the Enterprise. The editor explained that the hotel and restaurant were built “on the European plan.” He boldly pronounced that the Enterprise was “a first class hotel and a credit to our city.” Oysters “served in every style” were frequently on the menu. The Isaacs family left for St. Louis in the fall of 1885.

Under the management of M. L. Frase. the hotel was renamed the City Hotel and in 1897 was the only hotel in the city to offer $1.00 a day house in the city.

Murphy’s Hotel, 411-415 N. Main, Newton, Ks

The building was purchase by Joseph W. Murphy in approximately 1896. He opened Murphy’s Hotel shortly after. Joseph W. Murphy knew how to run hotels. By 1911, he owned four hotels in neighboring towns and employed fifty-two “skilled assistants.” The rooms were “first class with steam heat, electric lights and hot and cold water.” Murphy’s Hotel and Restaurant 411-415 N. Main. (1902)

According to newspaper reporting, Murphy planned to build a five story, 100 room fireproof hotel to replace the one at 411-413 N Main. It is unknown what happened to those plans.

In 1919, after 23 years in the hotel business, Murphy sold the business to Fred Fuge.

Carrie van Aken: Newton Business Woman

Born in Michigan in 1867, Carrie Douglas Van Aken would grow up to be a “pioneer resident” in Harvey County, Kansas and an active businesswoman.

Shortly after Carrie and Edward van Aken were married in November 1884 in Michigan, they moved to Nickerson, Kansas where Edward was employed by the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad as a telephone operator. Both of their children, Mildred and Lawrence, were born in Kansas.

In 1896, the AT&SF Railroad division headquarters moved back to Newton. As a result, Edward moved his family to Newton. For the next 43 years, until his death in 1931, Edward worked as a telephone operator for the Santa Fe Railroad. The family established a home at 120 East 1st after 1910.

Carrie soon became involved in the thriving restaurant/ hotel business in Newton.

In 1905 Mrs. Carrie Van Aken is listed as bookkeeper at the Murphy Hotel and Cafe located at 411-415 Main, Newton. Joseph W. Murphy was the proprietor. Her daughter, Mildred, also worked for the Murphy Hotel as a clerk in 1902. Eventually, she established her own restaurant business. The 1917 Newton City Directory, Carrie Van Aken is listed as the proprietor of the Auditorium Cafe located at 122 E. 5th, right across from the Santa Fe Depot. During this time, she also served as secretary on the Chamber of Commerce.

More on Carrie Van Aken’s businesses ventures.

Another tragic story associated with the Murphy Hotel is the one of Mary Janke.

The stories on key tag could tell.