by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

“Hundreds of automobiles were assembled in a circle . . .”

On Tuesday evening, September 12, 1922, a gathering was held on a rural property located in Section 3, Newton Township, Harvey County, “just northwest of where the new Santa Fe Trail leaves the railway track and turns north.” A reporter for the Evening Kansan Republican described an event where

“hundreds of automobiles were assembled in a circle several hundred yards across with lights turn on a huge electrically lighted cross in the center. White robed figures guarded the approaches to the circle . . . it was stated that a class of several hundred initiates were received in the Klan.” -Evening Kansan Republican, 13 September 1922.

Participants came from Hutchinson, Wichita and “numerous other neighboring cities.” In addition to participants, the “public highways were jammed with sightseers.”

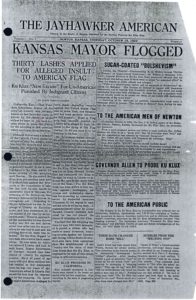

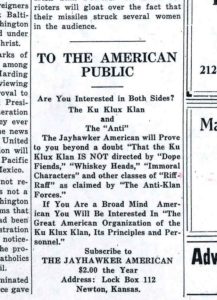

Notification of the event had occurred with handbills “distributed about the city last evening in some manner which recipients knew not of.” Many also received copies of a first edition of what was called the “official Kansas publication of the Klan.” The small four page publication called The Jayhawker American.”

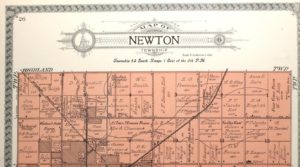

Both the 1918 Standard Atlas of Harvey County and the Mitchell Map of Harvey County, 1926 show E.O. Freeman, J.J. Steinkirchner and C.F. Molzen as land owners in section 3 of Newton Township, Harvey County, Kansas.

The Klan in Kansas

In 1921, the Klan began to get a foothold in Kansas communities, targeting the civic and religious leaders. In many communities, membership consisted of mainstream white Protestant men, including elected officials and community leaders. They organized social events for the community and church. They presented themselves a reform group promoting Christianity and “Americanism.” They actively worked for limits on immigration and were hostile to groups of people deemed “undesirable” including Catholics. According to one estimate the Klan had up to 200,000 members in Kansas during the 1920s. Historians refer to the time between 1915 and 1925 as the “2nd Klan.”

Most of the known Klan activities in Harvey County seemed to take place late in the fall of 1922 through spring 1923, including the meeting in the pasture.

In October 1922, rumors that several of the Republican candidates on the upcoming ballot were Klan members. To combat the rumors, C.D. Masters, Chairman of the Republican County Central, issued a statement printed in the October 31, 1922 Evening Kansan Republican regarding candidates and membership in the Klan. “There is not a Republican county candidate a member of said organization.”

In the November 23 issue of the Evening Kansan Republican, the editor noted:

“On general principles the Kansan is of course against the Ku Klux Klan, or any other organization or individual that presumes to try to supersede or set aside regularly constituted law and order. The editor goes on to note that “so far . . . there has been no breach of the law-no attempt at mob rule . . . or any of the violent conduct in the name of the Klan here” although, he noted, that this has not been the case in other Kansas communities.

The editor also noted:

“We have thought all along that the Klan movement was so utterly ridiculous that it would speedily die out as a useless and unworthy proposition, and we believe it would have done so, had not ardent opponents given it so much free advertising.”

Throughout the 1920s, there continued to be incidents in various Harvey County communities.

Donates Purse to Church

Hesston, 1923

Early in 1923, the Methodist Church in Hesston received a visit from the Klan. The experience as described in the undated clipping included with a letter written by Waive Kline dated 3 February 1923. According to the clipping, a twenty-four year old Newton man, Lyle Norton, was the spokesman of the group of 16. When asked why they had singled out Hesston Methodist Church, Norton replied:

“they had been observing the work of the churches in the county, and had learned that Rev. Tarvin was doing good work, but not receiving the support he deserved, and that the visit was made so that the people of the Hesston congregation many know that their activities were being watched.”

All 16 members were in full regalia, but only Norton removed his mask noting that he was “not ashamed of their organization” and he requested that the Evening Kansan Republican state that the organization is “not anti -Catholic, not anti-Jew, not anti-Negro, and not anti-anything — just pro-American.”

Norton was a Harvey County native, born to James & Maggie Norton in June 1899. The elder Norton had a monument business and Lyle likely worked for his father. The 1920 Census shows him living at home. He married Martha and by the 1930 Census they had a 5 year old son. In the mid-1920s, he owned Norton Tire Store at 614 Main in Newton. The 1940 Census indicates that he and his family moved to El Paso, Colorado.

The Ku Klux Comes To Town

Halstead, 1923

The visit to the 1st Methodist Church in Halstead was less friendly. Lydia Mayfield included a description of the event she called a “most ridiculous and shameful show of hypocritical bigotry and silly jingoism” in her “Halstead the Early Years”

In 1923, the annual Easter Cantata was held at the 1st Methodist Church in Halstead. Participants in the chorus were “musically gifted people of the town” usually Protestant. This year, however, one soloist was Catholic. Mayfield noted that the “Klan was on hand to prevent this terrible desecration.” Eye witness Grace Barkemeyer described her memory of the event.

“I have a clear picture in my mind of how things looked the evening of the Klan visit. I remember how Elmer Ruth looked around to see what made the chorus look so startled and how each one in the audience looked as they caught sight of the intruders.” –Grace Barkemeyer, quoted in Mayfield, “Halstead the Early Years”

The reporter for the Halstead Independent noted that “the leader made as short speech in which he berated the morals of the community and the churches, castigated the clergy and said that the Klan was going to weed out the sinners and anybody not one hundred person American.” At the conclusion of his speech, he announced that he was “not ashamed” and removed his hood “when the features of Lyle Norton of Newton were recognized by many.” After a short prayer, the leader put a few dollars on the pulpit for “moral and religious training of young boys and girls of Halstead” and the eighteen “hooded sheeted Klan marched out.“

Nobody knew for certain who the Halstead members were, but Lyle Norton was again the spokesman for the group.

The Klan held Their Regular Meeting

Sedgwick, 1924

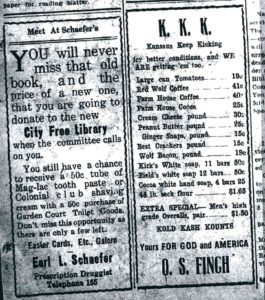

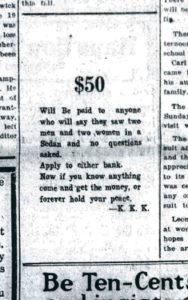

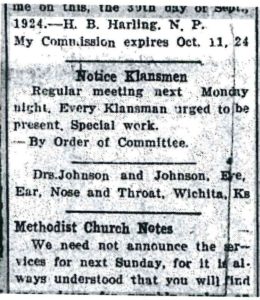

Several meeting notices and advertisements appeared in the Sedgwick Pantagraph throughout 1924.

O.S. Finch (1869-1940), was a businessman in Sedgwick, married with at least two children. His possible involvement in the Klan is unknown other than this advertisement.

Klan Parade

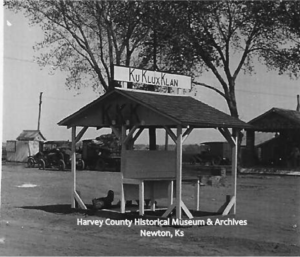

Newton, 1927

The Evening Kansan Republican, reported in 1927 that a “Klan Parade Was Held.” According to the notice in the August 8, 1927 issue, the Klan parade began at “Athletic Park coming in on Fifth, north on Poplar to Seventh and thence back south.” The column of participants was “two to three blocks long with three persons abreast, including women and children, all with full regalia except masks. A band headed the parade.” The parade was followed by a speaker.

By the late 1920s, the Klan was in decline in Harvey County. On January 25, 1925, Kansas became the first state to legally “oust the Klan” after a ruling by the Kansas Supreme Court that the Klan was a foreign corporation and need a Kansas charter to continue in Kansas.

Sources:

- Jayhawker American Vol. 1, Number 7, published in Newton, Ks, 19 October 1922. HCHM Archives.

- Newton City Directories: 1917, 1919, 1934, 1938, 1940.

- U.S. Census: 1900, 1920, 1930, 1940.

- Standard Atlas of Harvey County, Kansas, 1918.

- Mitchell Map of Harvey County, Kansas, 1926.

- Newspapers:

- Evening Kansan Republican: 14 September 1906, 11 March 1909, 20 March 1909, 28 June 1912, 23 July 1921, 22 March 1922, 5 April 1922, 3 May 1922, 19 May 1922, 7 July 1922, 21 August 1922, 13 September 1922, 6 October 1922, 20 October 1922, 21 October 1922, 28 October 1922, 30 October 1922, 31 October 1922, 23 November 1922, 4 December 1922, 2 April 1923. 4 April 1923, 23 October 1923, 7 December 1924, 8 August 1927, 21 June 1946.

- Halstead Independent, 5 April 1923.

- Sedgwick Pantagraph: 14 February 1924, 13 April 1924, 6 September 1924, 11 September 1924, 2 October 1924, 9 October 1924, 16 October 1924, 28 October 1924.

- Clipping of Klan Activities in Hesston, 3 February 1923 HCHM Archives.

- Kline, Waive to Glen Wacker, letter dated 3 February 1923. Wacker Collection, HCHM Archives

- Mayfield, Lydia. “Halstead: The Early Years” Halstead, Ks, 1987. HCHM Archives.

Additional Resources

- Sloan, Charles William, Jr. “Kansas Battles the Invisible Empire: The Legal Outster of the KKK From Kansas, 1922-1927” Fall 1974 (Vol. 40, No. 3) at https://www.kshs.org/p/kansas-historical-quarterly-kansas-battles-the-invisible-empire/13247

- Grinspan, Jon. “The KKK’s Failed Comeback” http://www.whatitmeanstobeamerican.org.

- Jones, Lila Lee. The Ku Klux Klan in Eastern Kansas during the 1920s. Emporia State Research Studies, Winter, 1975.

- Rives, Timothy. “The Second Ku Klux Klan in Kansas City: Rise and Fall of a White Nationalist Movement” Dwight Eisenhower Presidential Library. Kansas City Public Library, The Pendergast Years.

- Schruben, Francis W. Kansas In Turmoil: 1930-1936. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press, 1969.

- “The Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s” at http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/general-article/flood-klan.

- “Klan Painting” at http://www.kshs.org/cool2/klan.htm.

- Ku Klux Klan in Kansas – Kansapedia – Kansas State Historical Society at http://www.org/kansapedia/ku-klux-klan-in-kansas/15612.