by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

January 5, 1886 “was beautifully warm, sunny and very quiet. . .” but changes were coming.

Later, Christian Krehbiel, Halstead, recalled watching “flies flitting about the barn as if in midsummer” causing him to remark to another in German “Morgen gliegen sie nicht so.” (rough translation: ‘They won’t fly like that by tomorrow morning.”) Krehbiel’s words proved to be prophetic. By the next morning, “the temperature had dropped to 20 below zero and the wind was blowing fine snow around so that it was impossible to see.” (Halstead Independent, 1961)

In Caldwell, Ks, another farmer was also suspicious of the spring-like weather in early January. His daughter later told of how her father observed the weather “was so warm that the cattle stood and drank water because of the heat.” As a result, he “feared a storm and drove two cow ponies and a light wagon to the new village 18 miles away to lay in a supply of food stuff and fuel.” He barely made it home before the storm hit on January 6. (Carrie Omeara, Caldwell, Ks) Many other Kansans were not prepared for what was to come.

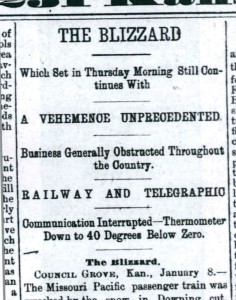

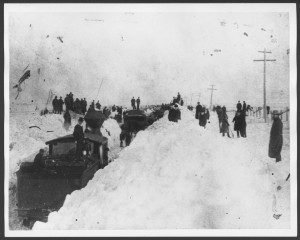

The Saturday, January 9, 1886 edition of the Topeka Daily Capital, noted that a blizzard, which had been raging with “a vehemence unprecedented” since Thursday, continued interrupting the railway and all communications. The thermometer registered 40 degrees below zero and many locations had drifts well over 6 feet.

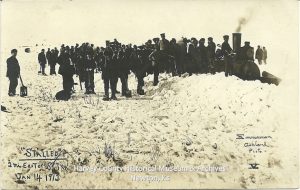

The blizzard began in northwest Kansas on January 6 and moved rapidly to the southeast and east. At 2:00 am on January 7, the storm roared through Ness City and by 5:00 am Wichita. In Harvey County, snow began to fall around 10:30 pm on the 6th and continued for the next four days. At times, the blinding snow made objects over 20 feet away invisible.

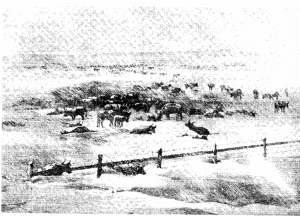

The number of Kansans that froze to death during the blizzard was estimated at 100. Many simply were not prepared. The primitive homes could not provide the needed protection against the chilling temperatures and high winds. Also devastating, was the loss of livestock. Cattle left on the open range drifted for miles until they dropped from hunger and exhaustion. In some areas of western Kansas, up to 75% of the cattle died during the storm.

Only three passenger trains made it to Denver the entire month of January in 1886.

The winter of 1911-1912 was another year for the record books. The most devastating storm hit on February 25 and 26, 1912. Drifts of eight to ten feet blocked roads and disrupted trains service. Throughout January and February regular temperatures of 20 below and weekly snowfall, left the ground covered with snow through March.

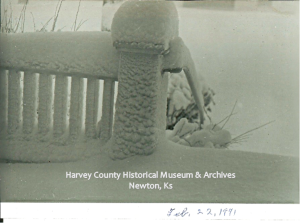

More recently, on February 21, 1971, the “worst snowstorm of the 20th century“ hit Kansas. For thirty-six hours most of the state was paralyzed as the storm, compared to the Blizzard of 1886, roared through leaving up to 14 inches of snow in Newton, Ks. The most impressive aspect of this storm was not the snowfall totals, but the driving winds that caused huge drifts. With winds howling at 25-40 miles mph, the blowing snow reduced visibility to near zero at times.

Do you remember the Blizzard of 1971? What about later ice and snow storms? Feel free to share below or on our Facebook page.

Sources:

- Newton Kansan 7 January 1886, p. 2.

- Topeka Daily Capital, 9 January 1886, p. 1.

- Halstead Independent 1961.

- www.kshs.org/kansapedia/blizzard-of-1886/11982, June 2003/modified June 2011.

- www.cappersfarmer.com/humor-and-nostalgia/anticipates-great-blizzard-omeara

- Lawrence Daily Journal-World 23 February 1971, p. 2. “Storm Nearly Equals Famous Kansas Blizzard”

- http://mikhaeltheteacher.com/?p=1950

- http://www.mikesmithenterprisesblog.com/2009/12/blizzard-of-71.html – “Blizzard of ’71” posted on 23 December 2009.

- Smurr, Linda C. Editor. Harvey County History, Harvey County Historical Society, Dallas, TX: Curtis Media Corp, 1990.