by Kristine Schmucker, HCHM Curator

“A Grand Day In Newton”

Parades, fairs and festivals were an important part of Harvey County history. The events were an opportunity for people to gather, both rural and city, for fun. Special days, like the 4th of July provided a natural opportunity. A full day of fun and activity was planned for the 1910 July 4th celebrations in Newton beginning with a parade on Main.

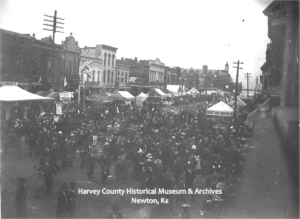

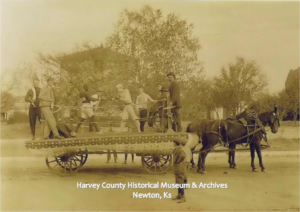

Early morning on the 4th of July, vehicles “from all precincts began to arrive bringing their loads of happy humanity.. . . by nine o’clock the streets were from First to Tenth streets with a gay crowd.” The parade down Main Street was the main event. Following the marshal of the day, Dr. Graybill, and the Newton Commercial Band, “came floats of every description, not a poor one in the lot.”

Pictures of the day show throngs of people gathered on Newton’s Main street.

“Floats of Every Description”

Excitement was in the air as Newtonians no doubt followed the news of the upcoming match of the “Fight of the Century” between Jack Johnson and James Jeffries in Reno, Nevada, at on July 4, 1910.

One float was created to depicted the upcoming match. Local firefighter, Aster Early dressed as the fighter Jack Johnson, a Black man.

Ed Wagner portrayed the “Great White Hope” James Jeffries.

“Fight of the Century”

Billed in national and local newspapers as the “fight of the century,” interest in the contest for the world heavyweight championship was intense. Jack Johnson, the seventh man to hold the heavyweight title and the first Black man to hold the title, challenged a retired, undefeated, James J. Jeffries.

The 32 year old Jack Johnson was in prime fighting form and successfully defended the title against 5 white challengers. Boxing insiders and the media worked to find a white man that could beat him. At 34, Jeffries had not fought in six years, weighed close to three hundred pounds, and was in no condition to fight. Under financial and social pressure, Jeffries consented to come out of retirement for the match. Jeffries was guaranteed $101,000 purse, with movie rights and a $10,000 cash bonus if he fought Johnson. He acknowledged that “portion of the white race that has been looking at me to defend its athletic supremacy may feel assured that I am fit to do my very best.” The media dubbed him “the White Hope.”

The match was set for Jul;y 4, 1910 in Reno Nevada. By June, Jeffries had lost weight due to intense training, however; his reflexes were not what they had been at his peak.

In the lead up to the fight, the press focused on the idea that Johnson and Jeffries were pitted against each other as representatives of their respective race. It was up to Jeffries to “restore collective racial prestige.” (McCormick, July 4, 1910: Johnson vs Jeffries)

On the day of the fight, Johnson entered the ring first and appeared outwardly confident as he was introduced to the hostile Reno crowd. When Jeffries entered, he refused to shake his opponents hand. Despite beginning the fight aggressively, it soon was apparent that Jeffries was not a match for Johnson. The match might have ended much sooner, but Johnson feared the consequences of an early knockout. By the fifteenth round a tiring Jeffries could not compete and Johnson scored the first ever knockdown against Jeffries. Two more knockdowns and Jeffries’ men stopped the fight as white fans rushed the ring shouting racial slurs. Johnson’s men had to form a protective barrier to get him out of the area.

Across the country Black communities watched with interest. In Hutchinson, at “the Holiness camp meeting tent . . . more than a thousand negroes had collected to pray for the black man’s victory.“

Immediately following the match, violence broke out across the United States. Perhaps the worst day for race riots in American history until the late 1960s. The fatalities were “overwhelmingly black.” To attempt to calm the atmosphere, cities across the nation barred the fight film from theaters. Congress attempted to pass a bill to ban all boxing films from theaters.

On the day after the fight, the Evening Kansan Republican is silent on the results.

Other area Kansas papers included details of the fight for the Kansas reader.

A statement from the fighters in the Leavenworth Post.

Film of the match.

Sources:

- Evening Kansan Republican: 16 June 1910, 4 July 1910, 5 July 1910, 9 July 1910.

- Hutchinson Gazette: 5 July 1910, 6 July 1910.

- Leavenworth Times: 5 July 1910.

- Leavenworth Post, 5 July 1910.

- Salina Evening Journal: 5 July 1910.

- Wichita Daily Eagle: 5 July 1910.

- http://www.ibhof.com/pages/archives/johnsonjeffries.html

- https://timeline.com/when-a-black-fighter-won-the-fight-of-the-century-race-riots-erupted-across-america-3730b8bf9c98